On January 15th, 2024, Guatemala swore in a new President, Bernardo Arévalo, an anti-corruption crusader whose landslide victory last fall shocked the country. Arévalo, a former diplomat, won the election by promising good governance reforms and an end to Democratic backsliding.

This is not the first time Guatemala has been promised peace. On December 29, 1996, the Accord for a Firm and Lasting Peace was signed, bringing the civil war that had engulfed Guatemala for 36 years to an end. Whilst the war did end, corruption and suppression continued, with the country effectively controlled by the pacto de corruptos, The Pact of the Corrupt.

The 36-year civil war was precipitated by the election of Jacobo Árbenz in 1951. His presidency marked a period of progressive reforms that antagonized American corporations with extensive land holdings in Guatemala. Three years after his election, Árbenz was overthrown in a coup orchestrated by the CIA. The coup marked the beginning of a period of intense political instability. The resultant civil war killed over 200,000 Guatemalans, roughly 85% of whom were indigenous Mayans.

The worst of the violence occurred in the seventeen months after General Efraín Ríos Montt seized power in early 1982. Ríos Montt launched a ‘scorched earth’ operation that targeted the country’s indigenous population. Within the first eight months of his tenure, 75,000 people had been killed. Montt was later convicted of genocide and crimes against humanity.

Jean-Marie Simon, one of the few foreign journalists on the ground as Ríos Montt launched his coup, arrived just before the conflict escalated.

Then a young woman working as a photojournalist, Simon vividly remembers the sense of fear that permeated Guatemala in the 1980s. “There was a pact of silence. Everybody had pseudonyms—I had two! I was followed. My phone was tapped,” she said. “You were always kind of looking at the reflection in the store window to see who was behind you.”

The fear extended far beyond journalists, Simon explained, reaching all corners of society. “A priest I knew had a tiny paper 12-month calendar. He told me that he wrote all his appointments in that little book. That way if the army came along, he could chew the pages really fast and swallow them.”

Author and journalist Francisco Goldman, whose novel, Monkey Boy, was a finalist for the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, overlapped with Simon in Guatemala in the 80s. She recalled an incident that occurred while walking through Guatemala City with Goldman in 1985. As they entered an alley, a group of men with machine guns jumped out of a dark car and confronted the pair. Reflecting on the experience years later, Simon noted the protection provided by her American citizenship. “I ran nowhere near the risk a Guatemalan would have in my position. They would have been killed or gone into exile,” she said. “Local journalists didn’t investigate anything… they often capitulated when on the Army’s payroll, or they just told a one-sided story.”

Goldman also recalled the repression of the press. “It was a heart attack every day…if a journalist didn’t play by the rules, which was not to report the truth, they could be killed, disappeared, or threatened so badly they fled into exile,” she said.

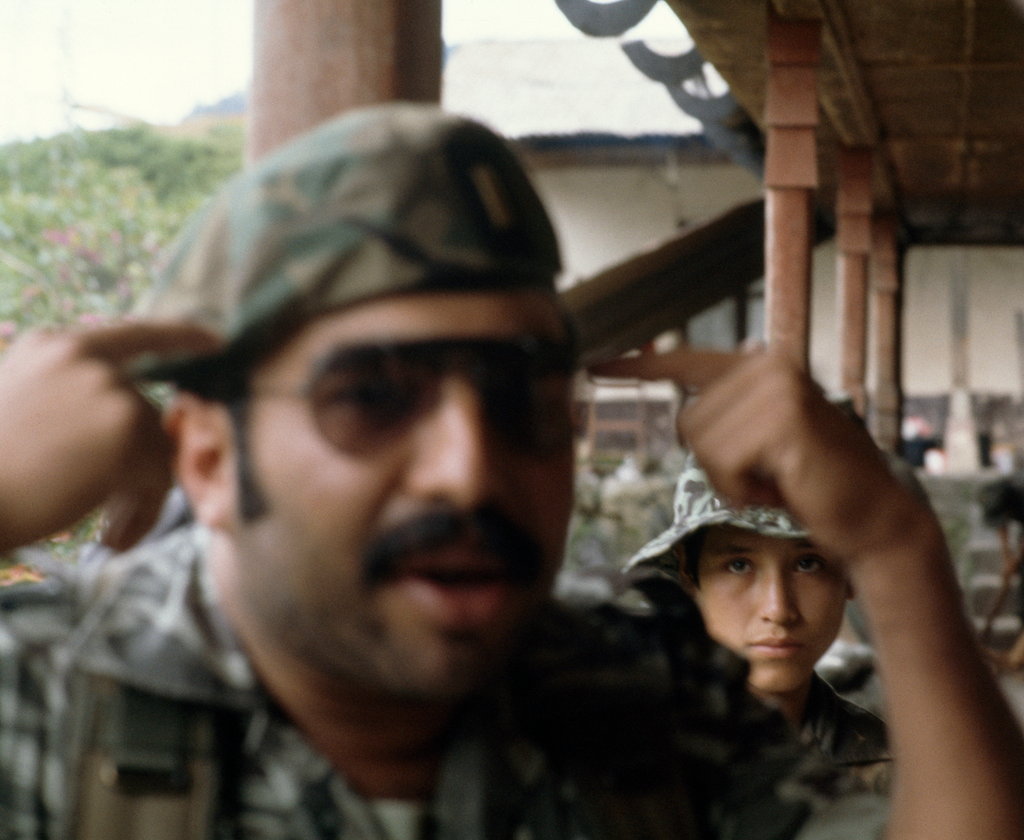

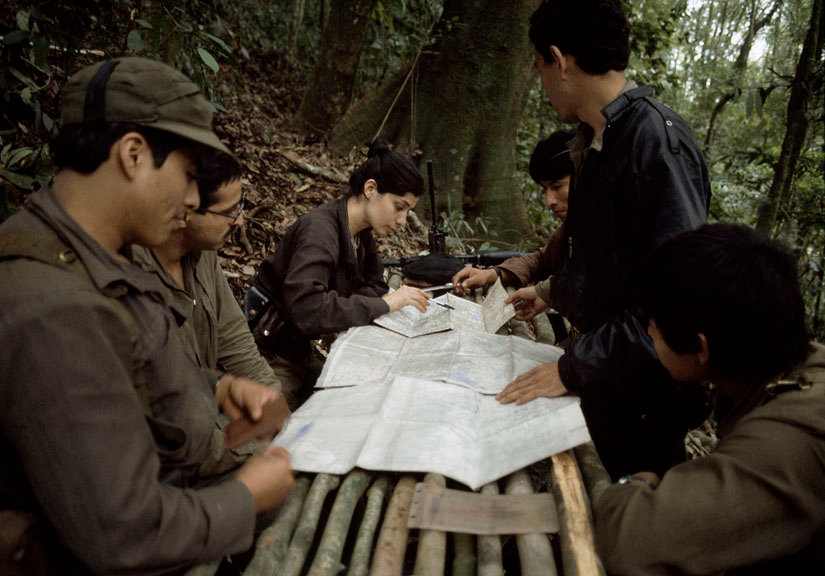

By 1991, both Goldman and Simon had left the country. “I was just so sick of it, so burnt out. I was so sick of violence. So sick of politics,” said Goldman. In her eight years there, Simon fixated on capturing all sides of war. Her photography revealed General Ríos Montt flanked by Junta members as he announced his coup; members of the guerrilla army of the poor—many of them children—training with sticks; the tortured and mutilated corpse of Héctor Gómez Calito, co-founder of Guatemala’s sole internal human rights group; and Mayan widows and orphans listening to an ideological talk at an army-run relocation camp.

By capturing the nuance of war, she hoped to depolarize it, erasing the notion of a simplistic struggle of good against evil. “It’s easy to believe a fairy tale where you’ve got martyrs and villains. There are certainly villains in Guatemala’s story, and there are some martyrs. But most people fall somewhere in between those two extremes, and it’s important to listen to those stories as well.” She continued, “people on the right are my friends as well, you know, they’ve not got horns and a tail.”

A war that began with rebellious left-leaning officers fleeing into the hills had turned into thirty-six years of violence, and though the Guatemalan government was responsible for the vast majority of the killing, neither side’s hands were clean.

Goldman echoed Simon’s sentiments. “The one thing that marks, at least the literary Central American and Latin American writers of my generation… is complete cynicism about both sides… complete revulsion finally over the guerrillas too.”

The 1996 Peace Accords should have opened the door toward a democratic state. Instead, due to lingering political divisions, the old alliances forged in the civil war between the military and business families persisted, and corruption in journalism remained. Soon, the same elite class that controlled Guatemala during the conflict, “The Pact of the Corrupt,” reasserted itself.

Jessie Cohn is the Executive Director of Amigos de Santa Cruz, an organization that aims to improve the lives of the indigenous people of Santa Cruz. She has lived in Santa Cruz for almost nine years. “There has never been a strong independent press,” she said. “From my perception, we’ve seen a step up in the last year of targeting journalists… The corruption just beats you down at every level… So you’re sort of in the darkness.”

In place of disappearances and political killings, the judicial branch has become the instrument of intimidation and repression. Dictated by the whims of powerful officials, the courts imprison individuals on technicalities or completely fabricated charges.

Goldman comments on the motivations of Guatemalan officials, “I know they really want to kill somebody, you know, they’re dying to kill somebody,” he said. “But they just can’t get away with it in the same way. They’ve found that putting people in prison is a really effective way of silencing people.”

The fate of José Rubin Zamora is emblematic of the government’s harnessing of the judiciary to silence critics. Zamora is the founder of three Guatemalan newspapers and one of Simon’s close friends. His newspapers regularly reported on the alleged corruption of President Alejandro Giammattei and his allies. Zamora was also the only newspaper publisher willing to name high-ranking Guatemalan government officials associated with the drug trade.

On July 29, 2022, Zamora was imprisoned and charged with money laundering, an arrest he characterized as “political persecution.” His wife was forced into exile in the United States.

“José Rubin was not a leftist by any means. He was just a guy who couldn’t not tell the truth,” Simon said. “He is not a corrupt person. He’s an honest investigative journalist and publisher.”

Throughout his career, according to Simon, Zamora has been threatened, attacked, held hostage, drugged, and kidnapped. “He is truly the guy with nine lives. The idea that he is languishing in prison is just outrageous,” she said.

Dagmar Thiel is the U.S. director of Fundamedios, a non-profit organization that advocates for freedom of expression in the Americas. Thiel notes that Zamora is far from the only imprisoned Guatemalan journalist. Many of those who join him are indigenous people who work in the provinces. They suffer from even greater discrimination. “They don’t have any international support because they are not well known. They also aren’t recognized in Guatemala because many believe that the only credible journalists are white and male,” Thiel explains.

Goldman adds, “Obviously, they’ve imprisoned our good friend José Rubin Zamora, but they’ve also chased a whole bunch of reporters into exile.”

Thiel notes that over 20 prominent journalists have gone into exile in the last year, an extremely high percentage of those working in such a small country. She also notes that many of the journalists she has worked with express a preference for jail over exile. “At least in jail, they could see their family members every couple of weeks. In exile, they meet nobody. They are free, but they don’t have any means of living abroad. It’s very hard for them to get a job, integrate into the community, and many who go to the U.S. don’t speak English,” Thiel said.

Simon notes that “there’s a whole cohort of Guatemalan journalists and former attorneys general still living right here in Washington DC, who are chomping at the bit to go back.” Yet, those in Washington represent just that small fraction of the most prominent and wealthy exiles. Most, whose pockets are not deep enough to get them to the United States, reside in Mexico.

Goldman notes that these exiles “as talented and as brave as they are, are hanging on by their fingernails.” Despite this, whilst many of the Washington exiles are eager to return, the young intellectuals in Mexico are inclined to remain there, attracted by the better educational opportunities for both them and their families.

The specter of the violence has also returned. Journalists are being murdered. “Last year, five journalists were killed. That’s one of the highest numbers in the continent. In Mexico, we had seven journalists killed, but Mexico has over 100 million more inhabitants,” Thiel said.

In 2023, a glimmer of hope for Guatemala’s freedom of the press shone through the darkness of years shrouded by ‘The Pact of the Corrupt’. On the 20th of August 2023, Bernardo Arévalo won the Guatemalan elections. Promising to tackle the entrenched political elite that weakened Guatemala’s judiciary and suffocated its freedom of the press, Arévalo secured over 58% of the votes. He told reporters: “The people of Guatemala have spoken forcefully. Enough with so much corruption.”

Yet, just hours after his victory, Arévalo’s party, Movimiento Semilla, was suspended by Guatemala’s Supreme Electoral Tribunal. Attorneys-General Consuelo Porras accused him of forging the signatures gathered to register his party, having found 12 dead people among the 25,000 signatories. Critics point out that she only launched her investigation into the party after Arévalo secured a surprise spot in the run-off.

These efforts to hinder a seamless transfer of power have drawn international condemnation, widely perceived as the initial stages of a coup d’état. Protests, for the most part non-violent, erupted across the country.

Cohn, whose work is integrated with the indigenous people of Santa Cruz, observed the nature of these protests, “It wasn’t one movement with national leadership. It was many different indigenous movements across the country who came together, passionate about contributing towards a better future.”

The scale of these protests is illustrated through their impact, paralyzing traffic on major highways and causing widespread fuel and food shortages across the country. Cohn comments on this impact in Santa Cruz: “Our local situation got very precarious in terms of access to basic food supplies. Our transportation was cut off, the boats stopped running so we couldn’t get anywhere. There was no cooking gas or cash at ATMs.” Indigenous leaders at the departmental level also put a lot of pressure on smaller villages to send forward people to join the protests. “They threatened to turn off electricity and revoke access to food if these towns didn’t send protestors.”

The pressure mounted, and the government’s hand was forced. On January 14, 2024, the courts ruled that Arévalo should assume his seat of power, potentially ushering in a new era of democracy in Guatemala.

Arévalo’s ascendance is indicative of a fundamental shift in politics in Guatemala as the masses reject corruption and turn towards a more democratic future. Goldman comments, “Young people opened the door for Arévalo’s victory, and then indigenous organizations in the countryside really played the critical role.” He cites two reasons for this assertion of popular power. First, “they’ve had a different upbringing.” Unlike their elders “they are not traumatized by the personal memories of a really violent uprising.” Second, “they’re more worldly, not just through social media, but everybody in Guatemala knows someone who has emigrated, so there is just a constant flow of information.”

According to Goldman, a major consequence is that “the Guatemalan press has been really unfettered, uncontrollable, really incredibly feisty.” Technological progress has allowed almost anyone to set up a digital news site, blunting the impact of the loss of so many reporters to exile. Even amid repression, it proved impossible to stop aggressive reporting because of the sheer number of active outlets. “The young people just keep punching and punching… the collective bravery of all those people is great armor against fear.”

“I mean, how can you not be happy about this? I think Arévalo is the real deal,” Simon said. “I love the way he comports himself. I think he is the most patient person I’ve ever seen in my life – the way he works a crowd and stuff, I don’t feel any artifice from him. So yes, I’m very hopeful about this. You know, I hope he slays dragons.”