In February 2023, Esmeralda Prego migrated from the Philippines to Nantou, Taiwan, to work as an in-home caretaker. She expected to spend her time helping an elderly grandmother with her daily routine. Instead, she found herself forced to work 13 hours daily—not only as a caretaker, but also as a hotel cleaner and a farm worker.

Every day, Prego was required to clean the hotel owned by the woman’s family; work at their farm feeding the poultry, duck, and fish; and finally care for the grandmother at her home. Her work day began at 7:30am, and she was only able to rest at 8pm.

Prego’s agonizingly long work days continued for five months until she told her friend, a caretaker working in another household, about her experience.

Her friend, who’s also a migrant worker from the Philippines, informed Prego that these additional responsibilities fell under the category of “illegal works,” or when employers force migrant workers to do labor outside of their contract provisions. The friend said that Prego needed to tell someone. She was connected by the friend to Serve the People Association (SPA), a Taoyuan-based non-government organization focused on defending migrant workers’ human rights.

SPA advised Prego to use her phone to document videos of her being forced to perform illegal works. Two weeks after Prego initially contacted SPA in June, SPA called law enforcement officers to remove her from her employer’s house, and relocate her to one of their Filipino migrant workers’ shelters located in the Yingge District.

According to China’s Ministry of Labor, as of April 2023, Taiwan is home to over 734,000 migrant workers, with the majority hailing from the Philippines, Indonesia, and Vietnam. In a country with a population of nearly 24 million people, migrant workers account for roughly 3.1% of Taiwan’s population. The majority of these migrant workers work in the manufacturing, fishing, and care-taking industries, according to the same report.

Because Taiwan doesn’t have labor laws that specifically protect the line of work migrant workers do, they often face exploitation across sectors. Lennon Wong (汪英達) is the Director of SPA’s Department of Policies of Migrant Workers. According to Wong, while migrant domestic workers and caretakers make up one of the smaller populations of Filipino migrant workers, they are one of the most socially visible groups.

“Most of these workers are caretakers, but they are also made to do the work of maids,” Wong said. “This [work overload] is one of the most common abuses.”

According to Wong, the most common problem facing migrant workers who work as domestic helpers is forced, illegal labor. He told The Politic in an interview that reporting the abuse is challenging, given that police are often reluctant to side with migrant workers. Most law enforcement officers are more concerned with determining whether a migrant worker is “illegal,” Wong said, rather than investigating possible exploitation. “[Law enforcement] receives bonuses for ‘catching’ illegal immigrants,” he continued.

In Prego’s case, after she had reported her employer, the police gave her employers a heads up that she made the complaint. On the day that law enforcement checked if Prego was working at the hotel, Prego’s employers simply stopped her from working there.

“The police went to look for her, saw she wasn’t there, and then said, ‘Oh, if she isn’t there, then the illegal work must not be happening,’” Wong said. “It was absurd.”

The police’s mishandling of the case not only delayed the processing of Prego’s case, but it also put her in danger.

Prego told The Politic that after her employers found out she had filed an illegal works report, they confronted her, and “asked her to lie to the police” about the situation.

Luckily, Prego had collected video evidence of the illegal works and sent it to the SPA. Upon receiving the evidence, Wong pressured law enforcement to revisit Prego’s case, and she was finally removed from her employer’s house.

At the time of the interview, Prego had been living at the SPA shelter for a little less than a week. She is awaiting employer approval for her transfer letter to another Taiwanese household.

While the SPA shelter houses migrant workers short-term like in the case of Prego, it also provides long-term housing for migrant workers like Sarah (granted anonymity due to her involvement in an ongoing case) who are fighting drawn-out legal battles.

When Sarah was preparing to work in Taiwan, her agent, who she was assigned to by her labor agency in the Philippines, had told her she was being assigned to take care of a six-year-old boy.

Only when Sarah arrived did she learn that the boy was terminally ill and needed to be attended to by an oxygen machine, heart monitor, and airway suction machine.

Working 16-hour days and sleeping in a storage room—all while under constant CCTV surveillance—Sarah was also tasked with cooking for the boy, cleaning the house, and doing the family’s laundry.

The “scariest” part of Sarah’s job was being forced to administer the suction machine — a practice, which according to Wong, should only legally be performed by trained nurses — over 50 times a day.

“During suction, there would be blood and the kid’s face would turn in pain,” she said. “I was scared because if anything [happens during suction] it would be my fault.”

After two months, Sarah contacted SPA and petitioned to terminate her contract. However, her employer withheld her salary and forced her to sign a contract stating that she owed him 70,000 NTD for breaking her 3-year contract.

While SPA helped Sarah regain her salary, Wong said that the employer never faced any legal consequences for the illegal work or shoddy contract.

Two other Taiwanese industries that are heavily populated by Filipino migrant workers are the factory production and fishing industries. Factory migrant workers are often assigned to perform the most dangerous and taxing jobs.

While Taiwanese factory workers often work the factory’s office jobs and are given “shorter shifts and New Years’ bonuses,” migrant worker factory workers are often saddled with the most dangerous tasks — usually with little to no safety gear.

Wong points to the 2019 death of Deserie Castro Taguba, a Filipina factory migrant worker who had been working at a Tyntek Corporation (鼎元光電) electronics plant in Miaoli, as evidence. In the factory, Tagubasi was tasked with using hydrofluoric acid to clean circuit boards. Despite the high toxicity of hydrofluoric acid, Tagubasi, along with the other migrant workers at the plant, were only provided gloves for protection. Tagubasi suffered an accidental chemical spill in August of 2019. Due to the lack of protection, she ended up dying from severe chemical burns.

In addition to working in low-protection, high-risk environments, factory workers also face grueling 12-hour shifts without overtime pay due to Taiwan’s “flex labor laws” that only regulate working hours in weekly periods. For example, while workers might only be allowed to work 50 hours a week, it’s up to the employer as to how to divide those hours. Due to this employer privilege, workers are often subjected to 12-hour shifts that allow factory managers to keep machines running for 24 hours straight. While the law mandates that workers deserve overtime pay for every hour beyond a standard eight hour shift, Wong explains that factory employers often “move hours around” in order to avoid paying migrant workers overtime.

“Because of the [redistribution of hours], the overtime premium is only calculated after the tenth hour [as opposed to the usual] eighth hour overtime limit,” Wong said. “This allows the employer to reduce overtime payment.”

The fishing sector faces a similar problem with unregulated working hours. Because there is little to no regulation for deep-sea fishing vessels in Taiwan as “the United Nations gave Taiwan a yellow card for its fishing practices,” according to Lennon, migrant workers are subject to long work hours and physical abuse on month-long fishing trips.

Wong said because there is a very strong “macho, aggressive fishing culture” in the fishing industry, physical abuse and labor trafficking happens very often on boating trips. According to a National Geographic report, among others, fishermen—mostly Southeast migrant workers—would face harassment from in-boat supervisors and often be underpaid or not paid at all for their labor.

“Many [migrant worker fishermen] reported that they have to work sixteen to twenty hours a day,” Wong said. “Sometimes the food is not enough and the drinking water is not enough, especially for distant-water fishing.”

In 2020, the U.S. Department of Labor caught wind of the practices in the Taiwanese fishing industry and added Taiwan caught fish to its List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor

In addition to keeping track of various migrant worker industry abuses and running its shelters, SPA also focuses on lobbying for the domestic helper profession to be protected under the Labor Standards Act. Wong said that because Taiwan’s domestic helper industry was created to sustain off migrant labor, there is no government incentive or public pressure to protect this line of work.

Wong said that beyond fighting for domestic helpers to be protected under the Labor Standards Act, it’s necessary to create a separate set of regulations that speak to the specific nuances of the domestic helper profession. This set of regulations should include ensuring that domestic helpers who live with their employers are guaranteed an individual bedroom where they aren’t surveilled and subjecting employers to spontaneous labor inspections.

“Migrant workers are one of our most vulnerable groups, so it’s essential that they are protected under law,” Wong said.

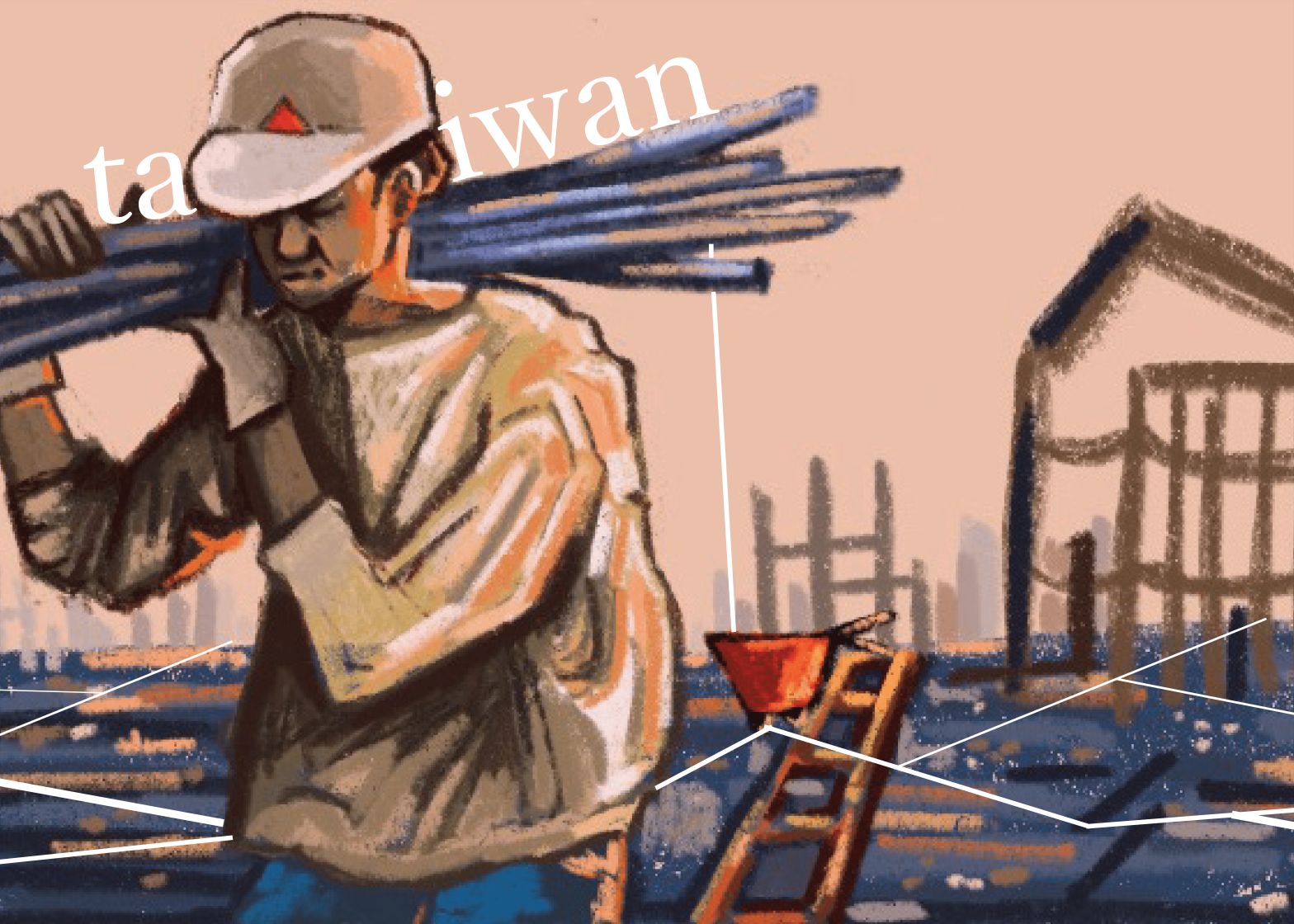

Cover image: Original Graphic (Malik Figaro/The Yale Politic)