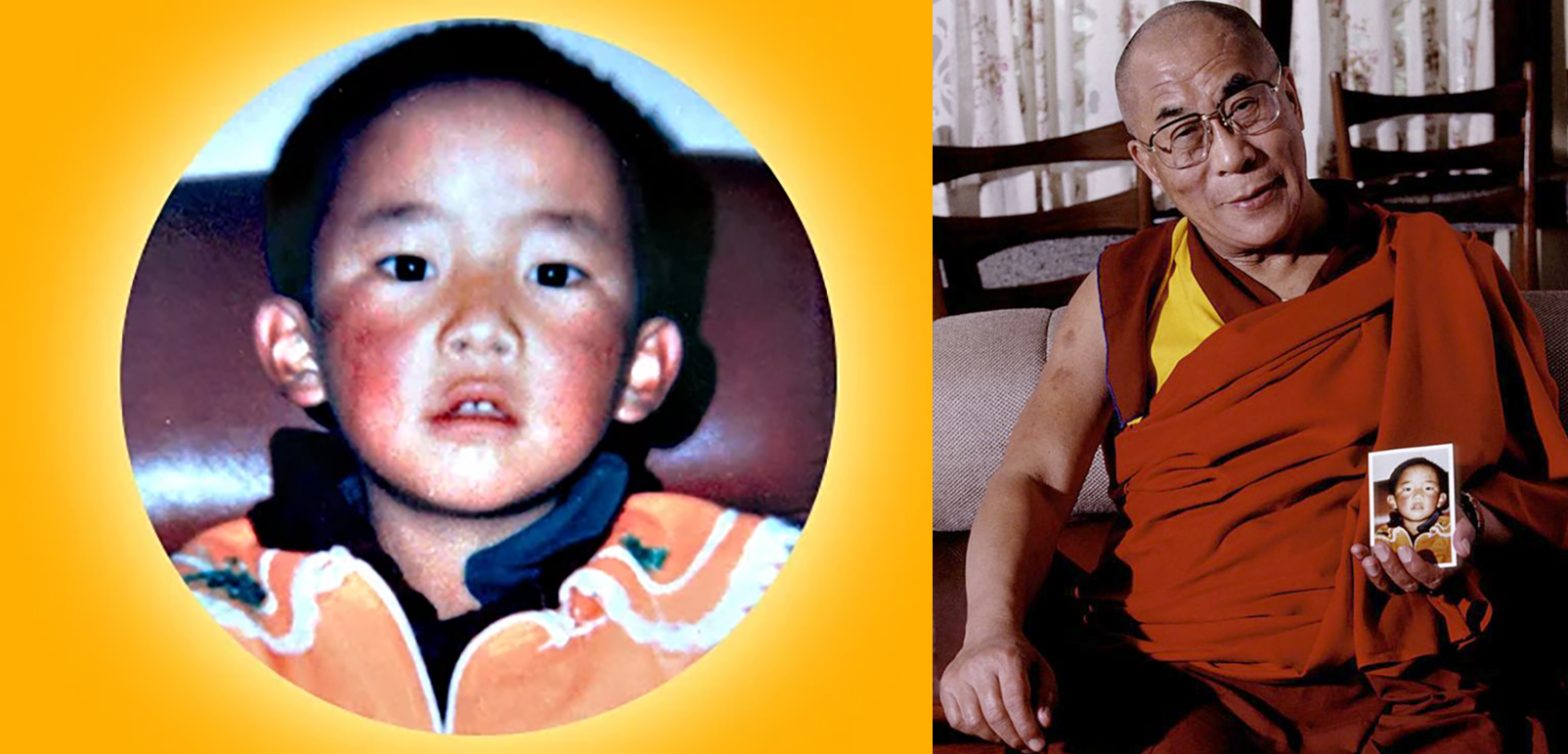

On an otherwise sedate afternoon in May 1995, residents of a remote village in Lhari, Northern Tibet, watched in stunned silence as armed men stormed into one of the town’s homes, snatched a family of herders, and fled as quickly as they had come. This was no ordinary abduction. The kidnappers’ target was a six-year-old boy who held the key to Tibetan Buddhism’s future––Gedhun Choekyi Nyima.

Murmurs of Nyima’s abduction spread quickly, first to the capital city of Lhasa, and then to the world beyond. The boy, who became the world’s youngest political prisoner, has not been seen nor heard from since.

Just three days before his kidnapping, it became abundantly clear––perhaps to everyone except Nyima––that the boy’s life was about to take a dramatic turn. On that day, the 14th Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso, recognized Nyima as the 11th reincarnation of the Panchen Lama, the second highest spiritual authority in Tibetan Buddhism. Following the announcement, monks at the Tashi Lhunpo Monastery, the monastic seat of the Panchen Lama, began eagerly preparing for the imminent arrival of their new lama––decorating his chamber, readying their youth, containing their excitement.

At this holy site, the boy would have spent the remaining years of his childhood learning Buddhist philosophy and Tibetan language, history, and culture. Each day, he would have risen early for traditional rituals and meditation. He would have spent his evenings practicing for a lifetime of performing religious ceremonies.

Occasionally, his daily routine might have been interrupted by a phone call with his exiled spiritual mentor, the Dalai Lama. They would have had many conversations over the years, in which the man whose magnetic charisma had earned him global stardom would mentor the boy.

Memories of his childhood home in Lhari would have grown distant as Nyima would grow into his role as the second highest spiritual authority in the land.

It is hard to fathom how this curated life of rigorous education and spirituality would have molded the boy. It is even harder to speculate on how his teachings would have shaped the lives of others. But Nyima never made it to Tashi Lhunpo.

Nyima’s kidnapping was the boiling point of a highly politicized six-year search for the 11th Panchen Lama, which itself was a manifestation of a long and complex history between China and Tibet.

The Mongol invasion of Tibet in 1240 marked the first time China imposed direct control over the region. The secular Mongol Emperor granted Tibetan religious leaders limited political autonomy in exchange for religious legitimacy in what has become known as the patron-priest relationship. The Qing dynasty (1636–1912) was the last to uphold this relationship with the Dalai Lama––by then the leading Tibetan Buddhist authority––by granting him a role as the Qing emperor’s spiritual mentor. But when the protectorate declared its independence in 1913, following the fall of the Empire during the Chinese Revolution, China refused to recognize the move.

Tibet remained a de facto independent state until 1950, when it was annexed by Mao Zedong’s People’s Liberation Army. One year later, the People’s Republic of China and Tibetan negotiators, under duress, signed the Seventeen Point Agreement, retroactively legitimizing China’s “liberation” of Tibet from imperialism while promising to safeguard the Tibetan religio-political system. The international community has come to recognize the Seventeen Point Agreement as a ‘marriage certificate’ of a tumultuous modern union.

However, it was not long before Tibetans took to the streets to file for divorce. A series of uprisings broke out over the next decade, most acutely in 1959, when rumors swirled that China was planning to kidnap the 14th Dalai Lama and take him to Beijing. The Dalai Lama subsequently fled to Northern India. Dharamsala, a serene intermontane city known for its lush greenery and unassuming charm, has housed the Tibetan-government-in-exile, and its nationalistic struggle, ever since.

But the 10th Panchen Lama, the man who preceded Nyima, stayed in Tibet. For the first time since the early 19th century, a generation of Tibetans––in Tibet and in exile––would grow up without simultaneous access to both of their highest spiritual leaders as result of tight Tibetan border controls. Initially, large swaths of Tibetans traveled to India in hopes of glimpsing the Dalai Lama, but this number faltered in ensuing decades as China imposed harsher controls. Last year, a handful of people undertook the daring journey.

The 14th Dalai Lama and the 10th Panchen Lama––traditionally spiritual mentors to one another, each solely responsible for recognizing the other’s reincarnation––would never see each other again. In 1989, the 10th Panchen Lama’s passing ignited a highly-anticipated war of claims over who would have the final say over his successor.

For centuries, the Tibetan people entrusted their religious leaders with unilateral control over the search process for reincarnated lamas. But since the 1950 Chinese takeover, China has claimed responsibility. The country’s ultimate goal in taking over the selection process was to further establish itself as an authority in the minds of the Tibetan people and to select a lama who would be open to Chinese influence.

China set out to select a Panchen Lama under the auspices of abiding by Tibetan Buddhist tradition, in which high lamas use clues from the previous lama’s death to search for children born with special signs around the same time. It often takes years to nominate children as candidate tulkus––masters of Buddhism––who are then tested to see which of them is the true reincarnation of the previous lama.

The current Dalai Lama was identified as a tulku at the age of two and enthroned two years later after correctly identifying the 13th Dalai Lama’s personal belongings.

But when China formed a search committee of tulkus in 1989, following the death of the 10th Panchen Lama, it broke centuries of tradition by dispossessing the exiled Dalai Lama of the right to ultimately recognize the reincarnation. Instead, it mandated the use of the Golden Urn, a centuries-old artifact with newfound relevance as the rationale for China’s purview over Tibetan Buddhist affairs.

The Qianlong Emperor gifted the urn, a copper pot, to Tibet in 1792. The Emperor ordered Tibetan monks to confirm their reincarnations by drawing candidate names out of the pot, and it has since been used to identify four Dalai Lamas. Interestingly, the urn has been accepted––albeit to varying degrees––by Tibetan Buddhist leaders over the years as a viable tiebreaker between contentious candidates.

In an effort to hoodwink China, the head of the search committee, Chadrel Rinpoche, secretly approached the Dalai Lama at the end of the search process with a candidate he believed was the Panchen Lama’s true reincarnation. The Dalai Lama agreed and privately recognized Nyima as the 11th Panchen Lama. Rinpoche then set out for Beijing to steer the committee towards Nyima and dupe the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) into believing the boy was its selection. But while Rinpoche was in Beijing, the Dalai Lama went public with news of a new Panchen Lama.

Chinese officials immediately arrested Rinpoche and the rest of the search committee. Three days later, Nyima became the youngest political prisoner in the world.

Tenzin Lekshay is the official spokesperson for the Central Tibet Administration (CTA), the government-in-exile. Lekshay was wary of the time difference between Dharamsala and the East Coast and insisted on an email interview because a call would be “too late” for me. After reassuring him that I am often up to see the sun rise, he agreed to a 25-minute discussion at midnight about the CTA’s official position on the Panchen Lama. As he answered my first question, it became immediately clear that Lekshay’s unbounded passion for the issue would overshadow his concern for my sleep schedule––typically, Buddhist monks wake up at around 4 am. We decided to table our discussion just before 2 am.

Lekshay said that Nyima’s kidnapping is a universal matter of injustice not only because the young child’s family was indefinitely imprisoned without cause, but also because it deprived all Tibetans of a historically deep-seated thought leader. He continued that the entirety of humanity would have borrowed wisdom from the Panchen Lama, just as it has from the Dalai Lama.

Lekshay noted that the crime is symbolic of the systemic Chinese campaign to foist its political motivations on Tibetan Buddhists. He warned against being fooled by seemingly progressive Chinese interventions in Tibet, like refurbishing traditional monasteries. These, he insisted, are always made in service of an ulterior motive, like promoting tourism in the region.

“Right from the beginning, [China] had a problem in understanding Buddhism,” Lekshay said. “Mao Zedong whispered in His Holiness’ ears that ‘religion is opium’… and it still remains a poison in the eyes and in the mind of the Chinese government.”

Lekshay said that to abduct six-year-old Nyima is a breach of humanitarian law, which prohibits taking civilians hostage; meanwhile, to kidnap the Panchen Lama is a garrote around the neck of Tibetan Buddhists, who have turned to the high lama for moral and spiritual guidance for centuries. To add insult to injury, China suspended its diplomatic back channels with the CTA in 2010 and has since refused to provide evidence of Nyima’s wellbeing.

Lekshay stressed that the issue of the Panchen Lama’s kidnapping concerns the international community as well. Were it to turn its back on Nyima by failing to secure his release, it would be shunning the pillars of justice and universal rights that have governed world order for decades.

Despite China’s hostility, the Tibetan government-in-exile harbors sympathy for the country. Lekshay regretted that China is headed in “the wrong direction.” It would even be unfair to blame the Chinese lay person for his views on Tibet, Lekshay said. Such a person is just as cut off from information as a Tibetan.

“China has to wake up,” Lekshay said. “China has to change for the better––for the future. And there is a right path for China to lead [the world] in the future.”

Lekshay outlined the government-in-exile’s “middle way policy” on the Sino-Tibetan conflict, which derives from the Middle Path in Buddhism, a balanced approach to life that avoids extreme world views. Under this policy, China and Tibet would enjoy a harmonious relationship in which China would retain political and economic control over Tibet while allowing for “meaningful [Tibetan] autonomy”––the freedom to practice Tibetan Buddhism and preserve Tibetan Buddhist culture without interference or religious persecution.

Lekshay prays for the moral realignment and future prosperity of China. His government’s desired outcome is not an independent Tibetan state. Rather, it is a home for the Tibetan people where the Panchen Lama can be chosen and raised freely in a monastery and the Dalai Lama can return from exile to impart wisdom onto Tibetan Buddhists without fear.

“If you are supporting Tibet,” Lekshay said, “you are pro-justice. And justice is universal.”

While it is easy to view Nyima’s kidnapping as a categorical human rights violation and move on, such resignation ignores the intellectual rigor the issue demands.

Enter Robert Barnett, founder and former Director of the Modern Tibetan Studies Program at Columbia University and co-founder and former Director of the Tibet Information Network, a leading source of independent news on Tibet. No one has been more consequential in the study of modern Tibet than Barnett. His role in translating and publishing the most important document in modern Tibetan history is evidence of that fact. The 70,000 Character Petition was a critical report on the CCP’s Tibet policy authored by the 10th Panchen Lama in 1962. In 1964, Mao imprisoned the Panchen Lama for the report, which had been sent to his government behind closed doors, denouncing it as a “poisoned arrow shot at the party.” For decades, scholars entertained rumors about the document, but none outside the halls of the Chinese government had seen it. And yet, in 1996, the 70,000 Character Petition was anonymously hand-delivered to the office of a single scholar: Robbie Barnett.

I met Barnett to discuss the Panchen Lama at a deli in a London suburb. He immediately set the tone for our nearly 3-hour conversation. “You have to know China,” he told me. “You have to know Communism, you have to know Marxism, and you have to know Xi Jinping to make any reasonable statement about what they’re doing [in Tibet].”

I pushed back, citing human rights reports on Tibet that outlined abuses so grave that political ideology seemed irrelevant.

“Imagine the Chinese perception,” Barnett urged. “Then that human rights abuse no longer becomes an automatically meaningful self-serving unit of knowledge.”

Instead, Barnett prefers to analyze Tibet through a colonialist framework. He said it allows him to assess territorial disputes, track longer-term trends in China’s Tibet policy, and grapple with nuanced issues that “the human rights realm” and “abhorrent parachutist journalists” –– journalists who write bitesize stories about Tibet with limited knowledge of its history––are incapable of addressing.

According to Barnett, Tibet is a microcosm of China’s communist grand strategy. He stressed that the pace of change in Tibet will reflect the CCP’s progress toward its stated goal: true communism. As China is officially in the primary stage of socialism, the CCP seeks to increase proletariat consciousness, an effort it believes will render Tibetans grateful to China. In the interim, China’s policies aim to wean Tibetan Buddhists off their religious practices, preparing them for the next stage of Chinese communism in which they are totally sinicized.

On the issue of the 11th Panchen Lama’s kidnapping, Barnett urged me to consider the CCP stance on why replacing the Panchen Lama (rather than abolishing the lama system altogether) makes sense.

“‘We know that backward religious peoples who are not advanced only understand their own leaders, who have to have at least the appearance of the same culture as them,’” Barnett said, imitating the CCP. “‘Then we need a figurehead––we need a lama.’”

Barnett revealed to me that for the first three years of the Panchen Lama search process, China allowed the search committee to conduct a traditional search, even permitting Chadrel Rinpoche to be in contact with the Dalai Lama throughout. Their only intervention was requiring that the Chinese state eventually recognize the reincarnation. Barnett’s private interviews with those involved in the process at the time led him to believe that in 1993, the Chinese and the Dalai Lama were close to a deal that would allow both to recognize the same candidate.

But by 1994, the leadership of the CCP’s arm overseeing Tibet, newly appointed in the years following Tiananmen Square, changed its policy.

“The deal with Chadrel Rinpoche: canceled. The generosity, the kind of cloaked tolerance of the Dalai Lama: canceled. He’s now the enemy. Everyone has to denounce him. The deal on the next Panchen Lama: canceled,” Barnett said.

Barnett concluded that China’s policy shift was a political miscalculation. It violated the “gradualist” approach to educating the proletariat prescribed by Marx. He attributed the blunder to China’s benighted leadership in Tibet, a group of hardline CCP officials mostly parachuted in from Beijing with little expertise on the region.

By November 1995, China faced its most acute legitimacy crisis yet in Tibet. It had cornered itself into having to anoint its own Panchen Lama and could not capitulate by recognizing the Dalai Lama’s pick. Running out of options, China selected six-year-old Gyaltsen Norbu by way of a Golden Urn lottery, which photographic evidence suggests was rigged. Further distancing the CCP from Tibetan Buddhist tradition, the CCP opted to raise its Panchen Lama in the worldly streets of Beijing, not the gardens of Tashi Lhunpo, where the monks refused to house him.

“So now they’ve got to find a tutor for this new Panchen Lama to make him look traditional,” Barnett said of China’s dilemma. “[China needs to] produce a convincing Panchen Lama that won’t run away. They haven’t really succeeded.”

Barnett said that the CCP-recognized Panchen Lama is little more than a political figure in Tibet. His religious credibility among Tibetans, who still display pictures of the 10th Panchen Lama in their homes, is nonexistent.

China will certainly name a reincarnation of the current Dalai Lama––now 87 years old––when he dies. However, after the episode of the 11th Panchen Lama, the prospect of religious Tibetans being grateful to the communists is slimmer than ever. Barnett worries that the CCP has lost too much credibility among Tibetans to legitimately participate in a search process again.

For those skeptical about the CCP’s right to participate at all, Barnett notes that China adroitly oversaw the search process for the 17th Karmapa, another Buddhist master, in 1992. The Karmapa became the first living Buddha to be recognized by the atheist Chinese Communists. He was simultaneously recognized by the Dalai Lama. In 1999, the Karmapa defected to join the Dalai Lama in exile.

Some may take issue with the abstract notions Barnett deploys to scrutinize the very real issues affecting Tibetans, but the intellectual vantage point is not trivial. When I asked him what I should take away from our conversation, he was quick to answer: study China. “It doesn’t mean that Tibet isn’t important,” he said. “It just means you can’t understand Tibet without China.”

But to John Powers, a lecturer in Buddhism Studies at the University of Melbourne and a practicing Buddhist, the issues are too real to abstract. Powers, who studied under the Dalai Lama’s interpreter Jeffrey Hopkins at the University of Virginia and even attended the Dalai Lama’s 70th birthday celebration in Delhi, said China’s oversight of reincarnation is always illegitimate.

“Because the Chinese Communists are dialectical materialists, they don’t believe in reincarnation or the possibility of the transfer of subconsciousness from one life to the next,” Powers explained. “This means that they can’t say we have identified the transmigrating consciousness of the past Panchen Lama or, in the future, the Dalai Lama, because they don’t believe this is even possible.”

Lekshay expressed similar sentiments. He wondered ironically why the Chinese have yet to look for Mao Zedong’s reincarnation, given their avowed interest in the cycle of rebirth.

“For Tibetan Buddhists, it’s not the title that’s important,” Powers continued. “It’s that this person is believed to have the consciousness of the first Panchen Lama, and the second, and third, and so forth. It’s to be part of this lineage of transmigrating lamas who have been great teachers and meditators.”

Powers joked that China might as well have named a pick for U.S. postmaster. It has the same level of jurisdiction over both roles, he said.

But, of course, China has not annexed the U.S. Postal Service. Nor does it have the tangible authority to dismantle regional post offices that defy it. Nor do postal employees rely on China for their economic prosperity. The Dalai Lama is said to be contemplating prohibiting a search for his reincarnation, effectively eradicating the Dalai Lama lineage. It is hard to imagine this as anything other than a response to China.

***

The Middle Path may inform the fairest way to think about Tibet. As with most issues, the pursuit of a universally virtuous stance too heavily dilutes the complexities of the delicate historical relationship at hand. The communist brush that paints Tibet as a primordial Chinese province has frayed. The Tibetan people command a culture necessarily molded by their faith; the Chinese communists decry faith. The region is geographically anomalous: the so-called “Roof of the World,” Tibet houses the world’s tallest peaks, including Mount Everest. The Tibetan people speak their own language and comprise a singular ethnic group found nowhere else in the predominantly Han mainland China.

But painting China as a capricious human rights abuser pays little attention to detail. The politburo’s rigorous political calculations serve a long-term pursuit of Marxism. Each decision on Tibet is an essential deliberation for the CCP, capable of setting back or moving forward its political timeline by several years.

Not to mention, the Tibetan Buddhist faith is more resilient than most give it credit for. An end to the Panchen Lama lineage––and that of the Dalai Lama, for that matter––would upend centuries of tradition, but it would not threaten the religion’s survival. Thousands of lamas would remain, and some would naturally evolve to replace the religious stature of the lost lama.

More concerning is the difficulty of pursuing the Middle Path given the lack of academic discourse on the issue. The scholars I spoke with were remarkably eager to offer their time. All of them bemoaned the unfortunate reality that the situation in Tibet remains among the most undertaught issues at universities in the Western world.

In 2018, Yale’s only professor of Buddhist traditions, Andrew Quintman, departed the University because of a dispute over tenure, leaving Yale devoid of courses on Tibet.

Quintman, currently doing research in Nepal, will be bringing his findings back to Wesleyan University. Students at Yale––and those at many other universities across the country––are unable to access experts like Quintman to supplement an interest in Tibet.

Increased scholarship on Tibet would promote a larger set of founded opinions to subscribe to. More discussion about the issue would follow; more of us would run into each other as we navigated the halls of history in search of a way out. Perhaps this would move us closer to the intellectual equipoise for which Barnett advocates.

In New Haven, Tibetan immigrant Sherab Gyaltsen runs a Tibetan restaurant with his wife. Tibetan Kitchen boasts a cozy dining area adorned with colorful cloth wall decorations and framed clips of glowing New York Times reviews. Tibetan singing bowls line the shelves and a portrait of the 14th Dalai Lama as a young man hangs high above diners.

Gyaltsen, who was born in Dharamsala and describes himself as mildly religious, views the further study of Tibet as nonnegotiable; it is the most viable path to a resolution of the Sino-Tibetan conflict. For him, a resolution would mean the fulfillment of a lifelong dream: taking his daughter to Tibet. In the meantime, Gyaltsen resorts to annual trips to India to immerse his daughter in the exiled community.

“I want [my daughter] to learn her own language,” he said of his rationale for the trips. “Language is culture. If she just spoke English, I couldn’t expect her to think like a Tibetan.”

This fall, Gyaltsen’s daughter is headed to Stanford University. For now, there is no going back to Tibet.