Americans have had a steady craving for true crime stories since the 1960s. Psychologists and experts have long sought tangible explanations for the guilt-inducing pleasure of consuming entertainment depicting real human trauma. True crime stories have evolved over time, taking various shapes and forms, and within the genre are a lot more nuanced stories of violent crime and its effect on innocent people.

Recently, true crime’s evolution has caused even some of its staunchest supporters and consumers to question the direction of the perplexing genre. True crime serves multiple purposes, and I find it most helpful when applied in the form of helping others uncover unsolved crimes or spreading awareness of victims, rather than purely for the consumption of entertainment, in which case it can be problematic.

So what is true crime? True crime is widely defined as movies, books, TV series, podcasts, or any broad form of entertainment involving the production of real crimes that involve real people.

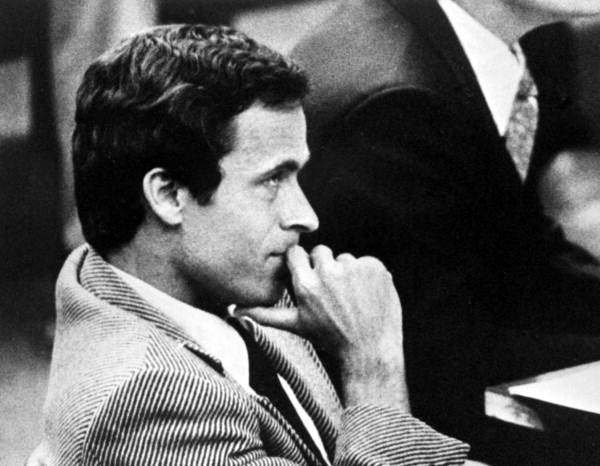

The roots of true crime lie in the 1960s, when only half of Americans owned television sets and the political assassinations of leaders like Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., the Kennedy brothers, Malcolm X, and the carnage of the Vietnam War took center stage. In the following decades, the emergence of several infamous serial killers—Ted Bundy, Charles Manson, and the Zodiac Killer—only made worse the fear that anyone could be the next victim of a brutal, calculated homicide.

Bonnie and Clyde, released in 1967, focuses on a couple in the 1930s who set out on a series of robberies, homicides, and kidnappings during the height of the Great Depression. The couple would go on to be two of the most romanticized criminals of all time. The movie was a box office hit, coming only behind classics like Gone With the Wind, The Jungle Book, and The Graduate in the prized year.

Two years prior, Truman Capote’s nonfiction novel In Cold Blood took readers on a third-person narrative experience through the lens of the killers in the Clutter family murders of 1959. By detailing the thoughts and actions from the perspectives of the killers, Capote allows the reader to anticipate the crime that eventually unfolds. From there, readers see the court process unfold for the two career criminals, and for decades following Capote’s work, the court process would be a focal point of most true crime stories. The book was an overnight success and is regarded as the second-best-selling true crime novel of all time.

Though Capote’s work gripped his audience and left many families overly fearful of a similarly gruesome attack, recent revelations and criticisms have called into question the authenticity of the stories told in the best-selling novel. As true crime has evolved, its creators have increasingly distorted reality. In the 1960s, when Capote’s work was published, the non-fiction label carried much more weight. Today, people don’t think twice about the details portrayed in reenactment documentaries of a serial killer’s last moments with their victims. There is less of an emphasis on “true” in the true crime label as reenactments often contain dramatized elements.

Before the turn of the century, there were fewer media outlets for true crime, which inevitably limited the scope of the genre. With widespread access to stories of personal lives hurt by an act of crime, true crime has seeped into all modern internet media.

***

True crime takes various forms, and there can be no one-size-fits-all approach to the genre. It would be hard to compare the conspiracy theory that Carole Baskin from Tiger King fed her ex-husband to her tigers to the repeated acts of homicidal wrath seen by the Golden State Killer, just arrested in 2018. To measure the effect, prevalence, and importance of true crime stories, all must be considered separate case studies.

With many recent true crime docu-series, there is a dramatization of the killings and a greater focus on the killer than the victims, something many critics find reprehensible. There is a stark difference between Lester Holt or Keith Morrison covering individual crime stories in a straightforward manner in episodes of Dateline, where the dramatization of acting is stripped from the story that took place, and fictional reenactments like the recent Ted Bundy film starring Zac Efron.

When watching a movie like Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile in correspondence with an episode of Dateline, one will quickly pick up on the drastic differences in the creation of true crime stories. A reenacted series featuring a serial killer like Ted Bundy will never serve justice to what was actually going on in a person’s mind to commit such heinous acts. True crime consumers are moving towards the romanticization of serial killers as A-list male actors take on the task of embodying the darkest of humanity.

However, one could also argue that there is a layer of complexity behind depicting the detailed mind of a killer as doing so shows how someone could devolve into such a state of mind.

Doctor Baskin-Sommers, a Yale professor who teaches a course called The Criminal Mind, lent additional insight on what types of factors could contribute to one developing a criminal mind. She said that environmental factors, like parental maltreatment, abuse or neglect, community and family poverty, or exposure to violence at a young age could spell disaster in one’s life. In saying this, she made the case that some true crime stories do not romanticize the killer in any way but rather acknowledge their complexity and many catalysts that lead one to commit an act of violence.

She mentioned that true crime disproportionately displays killers expressing psychopathic tendencies, knowing that the charm and grandiose characteristics can draw in an audience. “The vast majority of people with psychopathy are not serial killers, and most serial killers do not have psychopathy. We actually know very little about the psychological makeup of serial killers because it is so uncommon,” she said. In most fictional or nonfiction stories involving crimes like murder, the one perpetrating the violence is almost always characterized as one having psychopathy.

Doctor Baskin-Sommers emphasized, “The problem is many [true crime productions] sensationalize the crime, and in doing so they don’t provide any context for why someone did it. Very rarely do people just go around murdering people without any reason. And actually, very rarely do people repeatedly murder. Murder is usually a one-time crime, it’s usually done by people who know the victim. You would think [by] watching true crime shows that everyone on the block is a serial killer, and that’s just not the way it works.”

Society has grown desensitized due to the consistent consumption of true crime stories alongside the graphic content now widely accessible on the internet. Regular one-act homicides are no longer enough to keep a larger audience enthralled. The stories of serial killers have been the most successful productions in recent years instead.

Money is one of the many factors propping up new dramatized serial killer documentaries. Netflix jumps at the opportunity to create a new true crime documentary or docu-series featuring a star-studded actor leading the way. Since audiences turn out, Netflix is smart to invest more in the genre. There is a multitude of true crime content that glorifies serial killers, and having popular and attractive male actors on screen will inevitably make monstrous killers like Jeffrey Dahmer, Ted Bundy, and Joe Goldberg—the make-believe serial killer in Netflix’s You—seductively likable. Both true crime and psychological thriller shows alike demonstrate audiences’ growing obsession with the mind of a criminal.

***

True crime is easy-access and it is easiest to otherize the criminals. It requires more work to add nuance to a killer, and many watch true crime to remind themselves of their inability to do anything of the sort. Murderers are monsters, and nothing else.

While talking to Doctor Baskin-Sommers, I gained more insight into why ordinary people are inclined toward true crime. “True crime shows feed into this good versus evil narrative, which is just something that’s so foundational from an evolutionary perspective, and our way of socializing. There’s this kind of balance, whether the narrative is pushing a good versus evil trope,” she said. She went on to say that in many scenarios, when the script and recounting of a crime is less nuanced than it likely was in reality, we find ourselves “sitting there on the couch saying, we could never do this, we can never be like these people.”

True crime can perpetuate stigmas surrounding the criminal, but if executed with dignity, it can help various communities affected by crime. True crime advocates have been incredible forces for good in solving crimes, bringing peace to the victims and the families that carry their grief and making something positive of the negativity that true crime stories naturally induce. This has especially been done on platforms like Spotify and Apple, where the top ten charts for podcasts are dominated by true crime.

Podcasts are one of the most popular ways to consume true crime, as listeners of Serial, Crime Junkie, Morbid: A True Crime Podcast, and several others like them can for extended periods of time understand individual cases, many of which are unsolved. Another potential uptick for true crime podcasts today is the fact that the murder clearance rate—the number of cases solved by law enforcement—is at an all-time low. More Americans today are affected by unsolved crimes than ever before. Many of those affected are the ones who start podcasts in search of helping others find peace.

One of those people is Sarah Turney, whose podcast Voices for Justice helped solve the disappearance of her sister Alissa. Turney mobilized the public through social media and by way of her podcast, leading authorities to arrest her father twenty years after her sister mysteriously vanished. In an age where mysteries haunt people across the country, true crime podcasts led by forces for good—by people like Turney—certainly have found a place in the genre.

Unlike the newer Netflix productions of true crime stories, podcasts seem to play a significant role for the families of victims and the victims themselves. This is again where the complexity of the genre comes in. The scale of entertainment and information fluctuates given the different platforms disseminating stories of real-life tragedy. For example, in the many Jeffrey Dahmer creations on Netflix, entertainment and profit seem to be the driving force, whereas an investigative coalition of podcasters leading to the solving of Gabby Petito’s disappearance and death is motivated by a desire for discovery.

Psychology is at the center of what draws so many people to watch true crime. Many people watch true crime to better understand the unthinkable—to try and pinpoint patterns of a killer’s life, to test themselves in the positions of the victim, or to experience the thrill of the kill. For example, everyone had different reasons for binging The John Wayne Gacy Tapes or Dahmer, both of which dominated Netflix’s Top 10 list for weeks earlier this fall despite being drastically different in production and merit.

The John Wayne Gacy Tapes captures recorded audio of the killer Gacy himself, his twisted logic, and the direct points of view of the many people affected by his crimes. Though it would be quite hard to capture each one of the 33 victims, the docu-series allows for the story of Robert Piest to guide the way, and at least in the three episodes on Netflix, the viewer sees the real harm the crimes had on the surrounding community. At the end of the third episode, we see how new technological advancements and reignited social awareness of Gacy’s crimes paved the way for the identification of some of the previously unidentified victims. There is a disclaimer at the very end which reads: “If you believe a missing loved one could have been a victim of John Wayne Gacy, please contact the Cook County Sheriff’s Office.”

On the other hand, in Dahmer, each crime is acted out on screen, a vast departure from any code of ethics usually seen in the recreation of true crime stories. The intimacy of Dahmer’s killings at the forefront, families of the victims portrayed in the ten-part series claim the show has forced them to relive their deepest traumas. Families of victims suddenly find themselves unable to scroll through streaming services without seeing the face of Evan Peters in the uncanny form of Jeffrey Dahmer looking back at them, while knowing that millions of people are probably bundled up with popcorn ready to watch their loved one suffer at the hands of a killer. The situation is made even worse for families when Netflix has no obligation to contact them about a statement and does not bother to consult them about the show’s release.

The John Wayne Gacy Tapes consists of real clips, using non-fiction to lead the narrative of the brutality of Gacy, whereas Dahmer contributes to the reliving of crimes for countless families and communities still wrecked by their traumatic losses. The new Dahmer series creates opportunities to glorify a killer. Several people decided to dress up as him this Halloween. However, the issue is not all black and white, and according to who you ask, one may have a different thought as to what the potential benefits are of each type of portrayal on Netflix.

***

I grew up watching true crime, and Dateline episodes recycled in the background of my childhood. My dad would leave the room whenever my mom decided to turn it on. He would say, “Turn that crap off, it’s going to rot your brain,” to which she would always snap back, “At least I’m not ignoring the real world and in some fantasyland.” This dialogue always amused me, and I would laugh it off most of the time as they would too. But there is something to be said about why consumers of true crime consume it at all. Is it to enlighten oneself about the dark realities of humanity? Is it to live in the “real world,” as my mom would so often say? Or is it hyper-focusing on outlying unprovoked violent crimes as impossible to dodge, like a lightning bolt coming from a sudden storm?

The purpose of true crime has been questioned for decades already, is questioned today, and will be questioned for many more decades to come. True crime sits on a spectrum of entertainment and information, and between the two ends fall many podcasts, documentaries, television series, and biopics, which all compete for an audience.

True crime’s hold on the American public is one that psychologists will continue to study, but until there is a consensus on what acceptable forms are, we are left with the task of disseminating between engaging with purposeful stories of crime and the indulging of true crime as mere entertainment value.