The countdown to save earth’s final frontier has begun. The United Nations International Seabed Authority (ISA), an autonomous group of 167 member states which manages international seabed exploration and extraction, is currently meeting in Kingston, Jamaica to decide on watershed regulations regarding deep sea mining. The deep sea has grown increasingly attractive to mining companies since the advent of electric vehicles because minerals necessary for electric car batteries, including cobalt, nickel, and manganese, are rich beneath the seafloor. Rough mineral balls resembling dinosaur eggs, called polymetallic nodules, are located on and below seabeds and are highly coveted by mining companies for their dense metal concentrations.

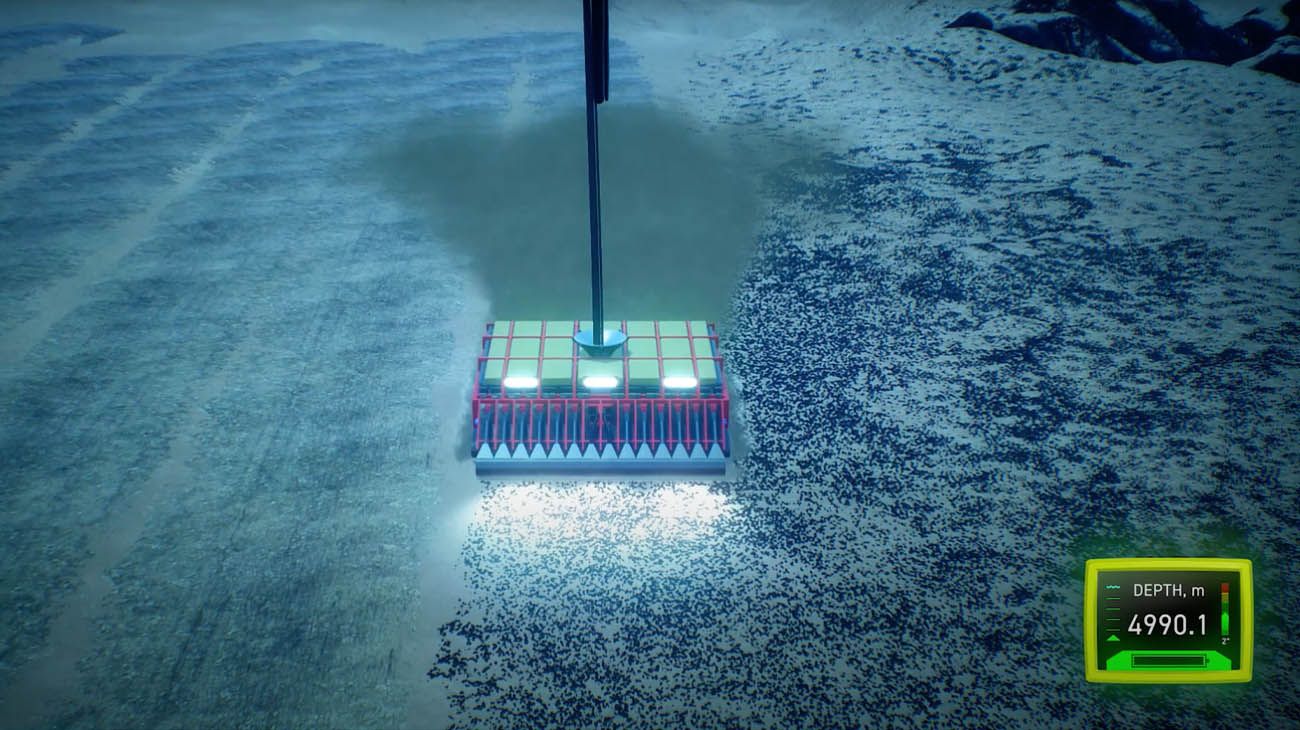

However, this highly profitable mining would come at a grave cost. The deep sea comprises 90% of the planet’s biosphere, performs integral climate regulation functions, and directly supports the survival of coastal communities. Seafloor exploitation would damage each of these crucial spheres—likely irreparably—while hypocritically purporting to forward a green future. Polymetallic nodules are often embedded under a layer of seafloor, which requires machines to scrape off the life-rich top layer of sediment to harvest them. This practice instantly kills some marine creatures, suffocates many via sediment plumes, and destroys the habitats of innumerable others.

Beyond these definable concerns, deep sea mining threatens that which we do not know: the species, phenomena, and yet undiscovered magnificence of the unprobed marine frontier. Deep sea mining would be a cudgel to the face of this masked beauty. Inelegant mining robots may trample over novel species and scrape away the next century’s would-be greatest discoveries without a trace.

The company at the forefront of the deep sea mining push is The Metals Company, formerly named DeepGreen. Mining companies need sponsorship from an ISA member state to appeal for mining licenses, and The Metals Company’s sponsor is Nauru, a tiny island country in the southwestern Pacific. It was previously rich in phosphate and was controlled by Australia, Britain, and New Zealand. These three governments exploited the island’s phosphate deposits for half a century until it became self-governing in 1966. Even in the ’60s, the mining damage on the tiny island was so severe that it was predicted to be uninhabitable by the ’90s. However, mining continued through the ’80s, and for a short time the Nauruans were extremely wealthy. But by the turn of the century, Nauru’s phosphate reserves were exhausted, and now only 10% of the island is habitable. This is why Nauru is sponsoring The Metals Company: after being involuntarily ravaged and exploited by colonial powers in the 20th century, Nauru, now in dire poverty and without options, must voluntarily exploit its last remaining resources to survive.

Within two decades of beginning mining, The Metals Company is estimated to make $95 billion dollars, on which it would pay royalties to Nauru and the ISA. Nauru sees these royalties as its last remaining lifeline. However, the island’s financial stopgap will be the world’s Pandora’s box. As of now, the ISA has not approved any deep sea mining, it has only approved exploration licenses. Once it establishes a precedent with The Metals Company and lays down procedures and rules for deep sea exploitation, the floodgates will open, and it will be incredibly difficult to instate a post-factum international moratorium on the practice. Nauru needs financial help, and it deserves to get it—from Australia, Britain, and New Zealand, not from another calamitous mining venture. The three colonial governments that controlled Nauru in the early 20th century owe full reparations to the island to repair the indigenous land which they laid waste to, and to support the people which they impoverished. These three Western powers owe it to both Nauru and future generations to atone for their past ruination, and to prevent its continuation.

Without intervention on the sponsorship level, it is unclear whether global organizations and activists can stop deep sea mining from moving forward. Groups such as Greenpeace and an alliance of nations including Palau, Fiji, and Samoa have spoken out on the issue to no avail. The ISA has been reticent and increasingly uncooperative with the media. (Each NGO and media outlet was only allowed to send one representative to the Kingston conference due to a venue downsize, and at least one journalism outlet, the DSM Observer, which specializes on deep sea mining news, was rejected from coming.) The ISA has also faced conflict of interest accusations, after its Secretary-General, Michael Lodge, was prominently featured in a DeepGreen (The Metals Company) commercial. Though this seems a flagrantly unethical, and even foolishly conspicuous display of closeness between the ISA and the mining venture, Lodge is still the ISA’s chief officer. He has ignored the pleas of scientists, who have created a petition against deep sea mining, and told the Economist that the impacts of mining “are by no means as catastrophic as environmental NGOs would have us believe.” Clearly, the sea has no protector in Lodge. Organizers and environmentally aware officials should pivot their efforts from swaying the ISA to swaying Nauru—removing the issue from the ISA’s jurisdiction altogether. The indelible stains of environmental colonialism are threatening to spill over, messily and uncontainably, into uncharted waters. We must rush to stem the flow.