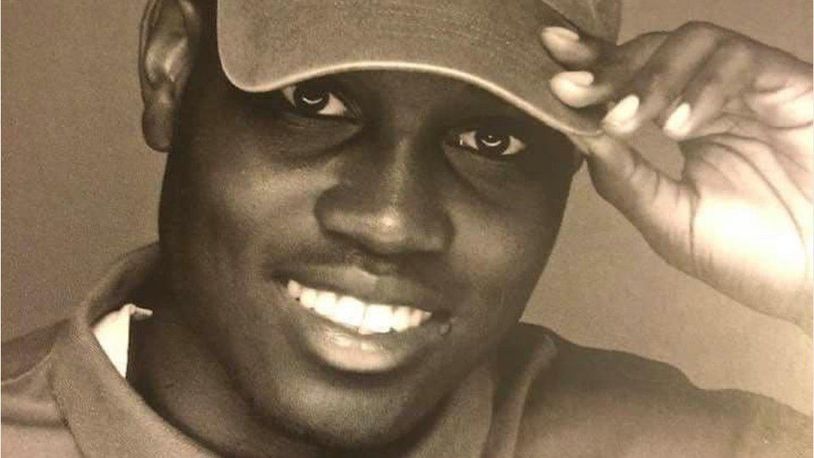

We lost another Black boy last spring. He was twenty-five and his friends called him Maud. In February of 2020, he was gunned down while out for a run.

Jogging in a Georgia suburb on the outskirts of Brunswick, Maud walked into a home under construction; he was profiled when he left. Suspicious of the Black boy in their neighborhood, a white man shouted for his son. The two grabbed their guns and loaded into a truck. A neighbor joined them in another vehicle. Without having seen a crime—witnessing nothing more than Maud leave a building—these men began their hunt.

Pursuing the innocent through the Georgia subdivision’s maze-like streets, they cornered him eventually.

He fought back.

So did the men.

A gun went off; first once,

then again,

and again.

Maud crumpled to the pavement.

No one was arrested when the police arrived. The men said they thought Maud was a suspect in recent break-ins. They called it a citizen’s arrest gone wrong. Permitted under an 1863 statute, Georgia’s citizen’s arrest provision has justified countless interruptions of Black life. None were murder, technically speaking.

Though the Brunswick District Attorney’s Office and the Glynn County Police Department opened an investigation into Maud’s killing, it would take months for that to mean anything real. From February through April, the case was transferred to a string of district attorneys who recused themselves because of connections to the man and his son. Both had once committed to protect and serve with the boys in blue.

Only after a video of the murder went viral were the men taken into custody.

In May they were charged.

In November they were convicted.

In January they were sentenced.

In the time separating Maud’s death and his murderers’ conviction, state legislators altered Georgia’s criminal code. They changed the statute on citizen’s arrests and recognized hate crimes in law. Today, the laws have changed and the men will end their days in prison. Some have called this justice.

But Maud is dead.

Last November, my heart sank watching so many receive the verdict with cries of joy. Torn between feelings of shock and relief and elation and rage, I felt empty watching Maud’s mother and father emerge from the Glynn County courthouse. Embraced by the music of jubilation—rapturous chants and cheers affirming that we shall overcome—they shined in triumph. Reflecting on the verdict, a reverend told the crowd that Brunswick would be remembered as the place where criminal justice “took a different turn.” Directing his speech to Maud’s mother and father, he continued in prophetic exclamation: “They lost a son, but their son will go down in history as one that proved that if you hold on, justice will come.”

I don’t know what we should call the verdict, but justice doesn’t feel right; this possibility faded with Maud’s last breath. Though the gravity of Maud’s story is not lost on me, though I’m grateful to see lessons of this tragedy memorialized in substantive change, I know that no law can balm the pain of a lost son. I also know that Maud is one of many.

When I was a child, it felt as though I descended from neglected and forgotten people. Though my parents raised me to honor the royalty of my melanin coat, the world worked against them. While they filled my head with visions of princes and kings—living, breathing reminders of the multiplicity and the possibility of Black life, the Black boys I heard of outside of my home were reduced to mugshots and police reports. Our lives seemed synonymous with little more than tragedy and misfortune.

With names like Emmett, and Trayvon, and Tamir, and Michael, and Eric, and George, and Ahmaud Arbery, their stories make clear to me all the things that you cannot do as a Black boy in America. Don’t make eye contact with white women; don’t walk with your hoodie up; don’t play in the park; don’t go on a run; don’t ask to breathe. You don’t do these things if you want to make it home at night. I think we sometimes forget the impact of this specter on our youth.

When Maud died, it was the Black boys that I thought of first—those who opened their social media feeds to see light and life taken from one of our own; those forced to watch Maud’s grisly death time and again without warning. It scares me that we’ve told these boys to look to Maud as an example of the system getting it right. It scares me because justice is not common sense legislation and recognizing murder as murder. I’ll know justice when there is no need for such legislation, when guilty verdicts are routine, not historic. I’ll know justice when men in uniform don’t terrify me and my walking down the street doesn’t terrify others. I’ll know justice when there is no need for Black boys to write articles saying that we’re tired and want more. This will be the day when I no longer dread having a son, when boys like me become elders, not hashtags.

The reverend said that if you hold on, justice will come.

I am still holding on.