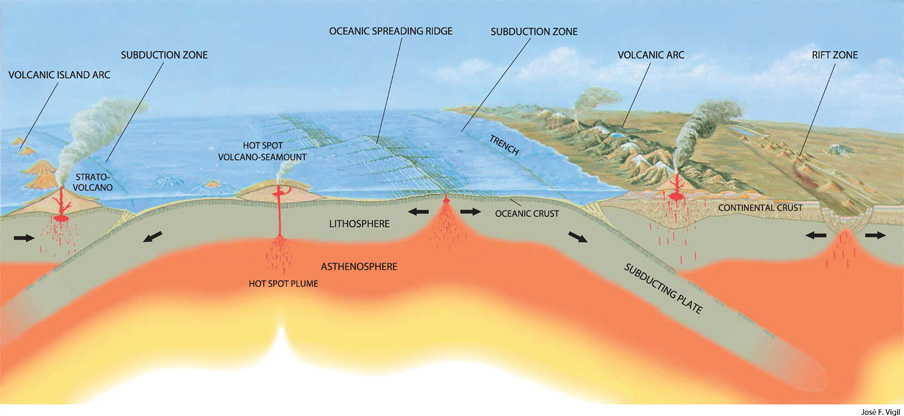

Four tectonic plates lie beneath the land of artificial intelligence. They are shifting in the U.S.-China landscape and are positioned for a monumental collision. Each one proposes the most advantageous way to regulate the data, robotics, and electronic systems that have become an integral part of global society. They all owe their origin to the ‘AI race’ between the U.S. and China.

In one corner is the trial-by-error, principally laissez-faire, corporate American plate, bearing the marks of tense friction between government and private companies. It experiments with different solutions and scales back after harm is detected. In another corner rests the towering Chinese plate, committed to pre-deployment, government curation, and central control. Instead of building on the errors of private sector innovation, the government tests its new technology before widely disseminating it to the public. Europe, trying to get the best of both worlds, is the third tectonic plate. And hovering alongside the three contenders is the fourth plate: industry itself. The private technology sector prioritizes proactive self-regulation and assures the government that it can manage regulation on its own.

“These plates are already starting to hit each other and cause earthquakes,” said Professor Nathaniel Raymond, a lecturer at the Jackson Institute for Global Affairs who offered the metaphor in an interview with The Politic. “These earthquakes will be integral to the shape of international trade between nations.”

Before framing the development of AI as a competition, which Raymond’s analogy suggests, American politicians should seek to understand the specific technological objectives of foreign governments to avoid frantically racing towards an undefined finish line. AI can bring together communities and encourage societal progress, but if left unregulated, companies and users are mutually worse off. The damage caused by foregoing ethical considerations has taken a toll on American companies. Facebook has recently been scrutinized for not addressing harmful body image and misinformation algorithms on its platforms. A few years ago, Google committed a serious blunder when its Photos application labeled Black users as gorillas.

Jin, a Chinese-born student at the University of Southern California who wishes to remain anonymous, found himself in the care of an American foster family at age 10. He spoke to The Politic, reflecting on the aftershocks of the U.S.-China collision. He returned to China during the COVID-19 pandemic and stayed there while cases remained low before beginning college in the United States. Jin vividly remembers China’s contrasting way of integrating technology into society. A QR code prevented him from entering his hometown following the outbreak of the pandemic. Surveillance cameras at a Chinese tech company he visited could identify someone based on their gait. Face scanners lined the entrances and exits of train stations. “People think that that’s how life is supposed to be in China,” Jin said, noting that they aren’t given an alternative.

These differences are particularly pertinent following China’s recent rollout of ethical AI guidelines published by the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST). The provisions aim for ambitious goals such as promoting justice, safety, and harmony with AI. They emphasize abiding by ethical norms and standards to maintain openness and empower ordinary citizens on digital platforms. To do so, the Chinese government is expanding its oversight by regulating Big Tech companies that traditionally control data and content recommendation. The country’s top-down model makes this process much easier than in the United States since Chinese technology companies heavily depend on what the government ordains.

***

Before diving into the Chinese model, it is helpful to understand how the four tectonic plates will likely slide in upcoming years. When varying approaches to regulating AI collide, the impact is far-reaching.

In the United States, a clear pattern of harm inflicted on individual users is typically the impetus for AI regulation. For instance, when the American criminal justice system implemented facial recognition technologies for predictive policing, certain racial prejudices — including different levels of policing based on the demographic makeup of certain neighborhoods — were identified after the harm was done. According to Raymond, the U.S. prioritizes market protection, and responses to ethical breaches succeed only if they manage to trigger preexisting legal precedents. In American democracy, the legislature determines the degree of oversight placed on tech companies, resulting in gridlock between conflicting parties.

The U.S. is known to be worryingly slow at responding to ethical concerns because of its lack of a centralized AI policy. The speed at which emerging technologies are deployed rapidly outpaces ethical and legal oversight. The Collingridge dilemma summarizes this best: It is easiest to regulate a piece of technology early in its development when it is not widespread, but by the time you understand what its problems are, there is no way to reverse its prejudicial effects because it is so entrenched in society. “This has become an excuse for bedeviled technology policy in the last 40 years,” said Wendell Wallach, a bioethicist at the forefront of AI ethics policy in China, a nascent field of study.

On the other hand, China is free from these quandaries because the government tracks the effect of its technologies before releasing them, according to Raymond. Through pre-deployment initiatives, the CCP curates data about how citizens respond to new sites or platforms before gradually introducing them to the general public. This is not a strategy exclusive to technology. China goes through a period of loosening control until the central government feels threatened by a particular development, which engenders a strong backlash.

A key example of this was Jack Ma’s growing autonomy from the Chinese government as Alibaba, the country’s largest e-commerce company, rose to the top of global markets. The founder failed to report the company’s acquisitions and transactions to the government, which eventually led to his abrupt disappearance. This is consistent with the justice and safety-oriented provisions proposed by MOST, which emphasize curbing the power of Big Tech companies.

China “reap[s] the advantages of central control until they reap all the disadvantages,” said Raymond. “It’s like a chess piece that can move ten spaces across the board until it can move none. This is the fundamental paradox of the Chinese government.”

The country benefits from pre-deployment and staunch oversight until it limits its innovation. However, the Chinese approach is not inflexible — in fact, it’s quite the opposite. The AI ethics guidelines released by China earlier this year outline how “agile governance” and “strategic decision-making” are crucial elements of their AI strategy.

In these guidelines, China has been careful to not explicitly mention its enlargement of governmental influence. The enumerated recommendations omit any detail of what the CCP can or cannot do while targeting companies like Alibaba. As the government takes on a more proactive role in promoting security and justice, it has instilled a feeling of trust amongst most of its citizens. Jin compared his time in the U.S. and China and observed that very few citizens in the latter country harbor any suspicion of encroachment or fear that leaders are overstepping their powers. Faced with much less skepticism than the United States, China can permit itself to launch new mandatory technologies that citizens will almost unilaterally accept.

Jin has experienced both worlds and weighed their respective benefits. “The Chinese media is focused on patriotism” to a degree that encourages the country to “overlook the mismanagement in the government,” Jin said. There is only “one narrative about the common good.” Jin mentioned the unethically sourced cotton in Xinjiang as an example of a stubborn attempt by the Chinese to portray the country’s human rights abuses as nonsensical attacks from foreign powers. The idea of “common good” is highly problematic because it only applies to issues that the government cares about. “I would be able to read articles from a lot of anti-semitic groups” in China, said Jin. People were also “fiercely racist against African groups in the comments of many articles,” and would “target you for not being patriotic enough” if you made a false move concerning Taiwan. This should not be seen as a fault in Chinese culture. If anything, it shows that Chinese citizens only have one source to turn to — the government — since they don’t look up to industry in the same way Americans do.

Nonetheless, Jin maintains that China’s quick recovery from the pandemic demonstrates the utility of state-led technologies. The government works with private companies to develop a QR code for everybody. “I was not able to enter my hometown coming back from the United States,” said Jin, holding up his phone to show his code embedded in his phone’s WeChat app. China was more successfully able to contain COVID-19 because of technological surveillance.

Another way that China is collecting information about its citizenry is through the country’s evolving social credit system (SCS). One of China’s major AI advancements, some Americans frequently misunderstand the system as an overarching database applied to every part of a person’s life. Jin notes that the type of credit depends on the industry, but that they all operate under the same premise of constructing a stored record. Jin argues that the system follows “common sense” in many instances. “The Central Chinese bank promotes one [variation] — if you don’t pay back the money you borrow, it will reflect in your social credit. You don’t want a housing bubble,” said Jin.

The same is true of laws. Indicted citizens or those with an unfulfilled financial contract have their information stored in credit files that may lead agencies or private companies to make adverse decisions, according to Jamie Horsley, a Senior Fellow at Yale Law School’s Paul Tsai China Center. With a good personal history, for example, one does not have to pay a deposit when booking a hotel, explained Jin. He believes that the SCS encourages people to follow rules and fulfill their societal obligations. Horsley reinforced this point. “The SCS records, shares, and in many cases… discloses information about violations of laws and regulations, court judgments, and legally effective documents,” she explained. “It does not record social behavior generally.”

It also has practical applications. The “qichacha” system enables people to use an app to determine the credibility of a firm. The app tracks the firm’s statistics, including employee social welfare and compliance with contracts, so that stakeholders can decide whether to invest in its services. This type of organization intends to prevent crises like housing bubbles.

To Jin, the benefits outweigh his concerns about government overreach because life flows more freely as a result. “It promotes a better society,” said Jin. But the stories he has heard from his family about the perils of dissent returned to his mind as he spoke. “My parents talked to me about my relatives being detained for criticizing the government.” One of them called “our supreme leader Xi Jinping a pig on a WeChat post” and another was caught “going to a foreign news website,” Jin recalled. Red posters line the streets warning citizens not to get scammed by chat rooms or online casinos, using foreboding messages like “One missed step gives ten years of sorrow.”

Horsley stressed that the SCS should not be thought of as generating and applying a score. If a court rules that the purchase of an anti-China book or skeptical online comment violates Chinese law, then the violation is “entered into the SCS, but would not result in any ‘score’ or other additional consequence not already provided for by law,” said Horsley. The principal focus of the SCS is to subtly nudge citizens towards a more law-abiding society by recording and publicizing past transgressions. The government intends to do this by making use of blacklists to track non-compliance and red lists for positive acts, but Horsley explained that the SCS is far from reaching this goal.

While the SCS does not currently make use of advanced surveillance technology, it is not difficult to see how the Chinese government is aiming for harmony with the law. Applying pressure to firms and citizens through records is just one way that it plans on getting there.

***

There are two diverging ways to approach the ethical AI dilemma. The first is through a competitive, realist lens. Raymond espouses this opinion through his opening tectonic plate metaphor.

“Nowadays, the civilian isn’t only commingled with the combatant, the civilian is the field of battle… they are the target,” he said. “It’s not just another form of state competition, it is the migration of state conflict and state military and intelligence into physical and digital infrastructure spaces, [including] healthcare, electricity, transport, and banking.”

Yale professor of management and political science Paul Bracken affirmed that “the race is just beginning [but] China hasn’t won… I happen to believe they are ahead at the moment.” However, he believes that multinational corporations are often an overlooked component of the AI race.

“Apple, BMW, and Walmart want to operate in the U.S., EU, and China, at the same time. BMW, for example, makes 40% of its profits in China,” said Bracken. These sprawling companies have thus tried to exercise their influence worldwide to reap the benefits that each region provides.

Bracken has witnessed this trend firsthand. “Recently I’ve been going to Europe a lot. I’m always at the high-priced restaurants that have sprouted up in Brussels. More and more it looks like K Street in Washington, D.C., the street where the big law firms, lobbyists, ‘think tanks,’ and business groups are located,” said Bracken. “[Lobbyists are] trying to get a favorable regulatory ruling from some part of the EU.” In other words, company representatives target whichever geographic location is most favorable to expedite the policy that aligns best with their interests. Brussels, the headquarters of the European Union, has thus attracted the corporate eye since Europe’s model promises strong incentives.

General Robert Spalding III, a retired U.S. Air Force brigadier general, does not have such a positive outlook about the AI race. “We are losing. To say we lost, however, would be to say that humanity has ended,” Spalding said. “As a Marxist-Leninist system, nihilism is a feature of [Chinese] society. This is not healthy where things like AI-powered weapons are concerned. Without the constraints of morality, there is no limit to the good or harm from AI,” he added.

Other academics and AI experts prefer to frame technological development as international cooperation instead of an AI race. “There are a lot of people out there who would like to recreate the Cold War, [pushing] the doctrine that we are in a new economic competition,” said Wallach. “Is that really what China is about or is that a narrative that some Americans are promoting?”

The international cooperation argument seeks to equally consider the short and long term ramifications of depicting each country’s pursuit of new technologies as a race. Abhishek Gupta, Founder of the Montreal AI Ethics Institute and a board member of Microsoft’s Commercial Software Engineering team, believes that cooperation is the most realistic way of framing current circumstances.

“I think the AI race as it’s been framed is necessarily a losing scenario for anyone who seeks to participate in it because it forces you to [pursue] paths that seem good in the immediate moment,” Gupta said. These paths are laced with elements which “do not yield much in the long run on the international front or on the front of making progress.”

Despite the profit that could be garnered from relaying technological breakthroughs to other countries, the status quo tends to maintain a competitive atmosphere, so much so that close allies can even be at odds with one another. British researchers in AI companies refuse to work with the U.S. government, for instance, while Chinese firms do. While the U.S. and the UK have recently fortified their maritime alliance, this is surprisingly irrelevant to the AI “race,” where it is every country for itself.

An anonymous expert involved in the AI ethics team of her company also underlined the inaccuracy of the “race” metaphor because the finish line looks different for each participant. She enumerated three levels of AI which nation-states aspire to reach. The first is Artificial Narrow Intelligence (ANI), which refers to AI that excels humans for one task, like a phone or self-driving car. The next is Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), namely AI that can perform all human tasks but more efficiently. This second step quickly leads to Artificial Super Intelligence (ASI), alluding to AI which is smarter than humans on every level.

The gap between ANI and AGI is significant. The latter is not necessarily a continuation of the former, and not every country is working toward the same goal. Nation-states that prioritize defense and weapons-based enhancement, such as China, are principally concerned with ANI, but American politicians often ignore this.

The anonymous expert believes that the idea of a race is also incompatible with the progress that ethical committees have made in recent years. “People speed up and don’t put ethics first,” she said. International conferences held between academics from across the globe are collaborative, useful ways to expound theoretical guidelines which then need to be applied concretely, according to the expert.

Gupta emphasized the importance of having a well-intentioned, robust leadership team to address AI concerns. “The Biden administration has brought on board people who have a great track record in terms of addressing issues through a broad socio-technical lens,” said Gupta, citing Tim Wu and Alondra Nelson as two influential examples.

Mia Dand, CEO of Lighthouse3, a firm which guides companies with the ethical adoption of AI, focused her work on introducing more voices to the conversation about AI. Dand published the first list of 100 Brilliant Women in AI Ethics in 2018 and funded the creation of a free online directory that helps recruit more Black and LGBTQ+ innovators in the AI ethics field. She addressed the U.S.’ pursuit of ethical AI development in light of Facebook’s appearances in court.

“The recent shift towards greater whistleblower protections, labor organizing movement[s], and a pro-democracy administration” is reason for greater optimism, she said. Both ends of the spectrum — an AI race that mirrors the Cold War as opposed to international cooperation — are concerned with interactions between nation states charting their own paths on the road of AI development. But how this AI will be governed is an entirely separate issue.

***

Industry has sought to protect itself from regulation under the guise of a “cult of innovation,” according to Wallach. Companies excuse themselves from their sometimes harmful technologies by supporting the narrative that government restrictions would intrude on free-market principles and innovation.

“Tech giants have used their massive funds, army of lobbyists, and complicit ratings-obsessed media to support their ‘innovation’ myth,” Dand said. “Any restrictions on their ‘freedom’ to engage in unethical and illegal behavior is decried as government overreach or ‘socialism,’ especially in the United States.”

Raymond added that Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act indemnifies most Silicon Valley technology companies from civil legal liability since they are treated as intermediaries republishing online speech. As the Collingridge dilemma suggests, these tech companies cannot predict the effects of their platforms in advance. “They’re like Galapagos tortoises that have grown up without any predators,” said Raymond. The evolution of these companies has been gradual and unobstructed, igniting ferocious backlash when the American government attempts to introduce restrictions. In a way, this might suggest that China’s authoritarian model is favorable to AI governance since companies are not completely unrestrained. Jack Ma’s disappearance reminded emerging Chinese companies that misalignment with the government’s standards is costly.

The goal should be to find an equilibrium between both systems. “We need a balanced approach, which includes solid government regulation that prioritizes public well-being… representation from vulnerable communities that are most at risk from these AI systems, and civilian oversight,” said Dand.

Dand expanded on the idea of a narrow, exclusive group of people controlling AI reform. “Lately, the AI discourse has been dominated by big tech and their funded academics, who, along with powerful non-profits, are actively helping reinforce the tech-friendly agenda,” said Dand. “It’s time to shift this power dynamic and make sure that AI benefits all of humanity, not just the privileged few.”

How exactly can this equilibrium be achieved if it feels like governments have already exhausted all possible approaches? The answer is to analyze AI governance in a more nuanced fashion. Raymond offered his version of a five-part analysis which can be instructive for this type of exercise.

The first and second solutions fall under hard and soft governance. The former mostly relies on anti-trust laws to rein in overweening technology companies. Soft government, on the other hand, is mostly driven by industry and civil society. “It doesn’t do much,” said Raymond, pointing to codes and white papers that fail to meaningfully influence regulation.

The third category, according to Raymond, are the revolutionaries. It’s not hard or soft government that will solve the problem, “it’s inventing entirely new technological and legal tools like blockchain and data trusts. If we invent a new thing for a new problem then we’re fine.” While the premise is sound, Raymond doesn’t believe that it is viable in today’s world because of its logistical complications. Another radical school of thought is refusalism, the fourth approach. It posits that all technology should be shut down.

The fifth category, with which Raymond personally identifies, can be called either translationists or neo-normalists. Voicing their general perspective, Raymond said: “We have encountered new technologies before, we’ll encounter new technology again. How do we transform existing normative frameworks so that we create new norms that are based on the previous ones? It’s not a radical reimagining or an orthodox application. We have to figure out how to translate.”

The categories contain more specific approaches. China is typically “very reactive,” according to Jin, who attributes many of China’s advancements to defensive measures against other threatening countries. China traditionally acts after the effects of a decision have fully materialized instead of taking preemptive steps to circumvent an undesired circumstance, though the same can loosely be said about the United States.

The implementation of ethical AI is multifaceted. Four approaches have been tried: the U.S. and its corporate friction, China’s top-down reactive method, Europe’s mix of the two, and the shield of industry itself. As these four forces dispute the best way to manage AI, criticism lands on a spectrum: One side maintains that the U.S. and China are in a cut-throat race while the other declares that international cooperation is a more productive way of framing the conversation.

Reconciling these perspectives is perhaps our best option. Yet, the ethical dimension should never be forgotten in considering how the U.S. and China develop their AI. Unregulated technology can be destructive, especially when countries prioritize speed over careful calculation. As with many other international relations issues like climate and human rights legislation, China has created separate standards while the U.S. remains stuck in political and corporate gridlock. Without global standards, AI is an uncontained monster that could go in any direction.

American politicians should recognize the varying objectives that other countries have while placing a firmer grip on companies that have shaped AI debates since their inception. The more concerted and polarized the competition becomes, the less likely that constructive ethical principles will be considered as AI continues to evolve, a dangerous premise with potentially devastating effects on humankind.