The death of local journalism is well-documented. Local newspapers across the country have been gutted, leaving towns across America without reliable information sources. The loss of a town’s first draft of history spells disaster for its second and third drafts, too. In many places, local historical societies are the last lines of defense against the total loss of local history. Local historical societies, a large portion of which are volunteer-run, collect and preserve publications, journals, photographs, and other ephemera to record an area’s history.

It’s an endeavor that often lacks the resources of national history, which can seem more appealing than its local cousin. Its scholarship is more accessible, its historians higher profile, and its impact seemingly wider. National history is relevant to an audience of millions, while local history, though also important, is often overlooked.

Michael Lotstein, university archivist at Yale, told The Politic, “There’s a saying that all politics is local. The same can be said for history.” He said that local history is a key element in illuminating our national past. “Any time you’re writing a history of some aspect of the history of the United States, whether it’s political, military, social, economic, oftentimes that history is built upon the local historical archives that document different areas of society.”

A national event rarely affects all communities uniformly, and the varying impacts of any policy or change are lost in nationwide statistics. The national story, though essential, necessarily excludes local stories, which may not fit perfectly into the national narrative, but are crucial to understanding the history of an individual place. Local histories are further challenged by the fact that fewer records and resources exist to research them.

Local history is often an important source for constructing genealogical records, which fuel the popular hobby and discipline of genealogy. In 2019, the market for genealogy services was valued at $3 billion, and was expected to grow. Family histories help people connect with their living kins and create a sense of family pride. David Rowland, the president of the Old York Road Historical Society, which preserves the history of the eastern Montgomery County region in Pennsylvania, estimates that one-third of the inquiries the society receives are from people hoping to learn more about their ancestors. The society’s volunteers help amateur genealogists search through social registers, newspapers, and the society’s other records for information on their ancestors. Understanding the lives of one’s forebears often requires understanding the context in which they lived: in other words, the local history of their town—which wouldn’t exist without local preservation efforts.

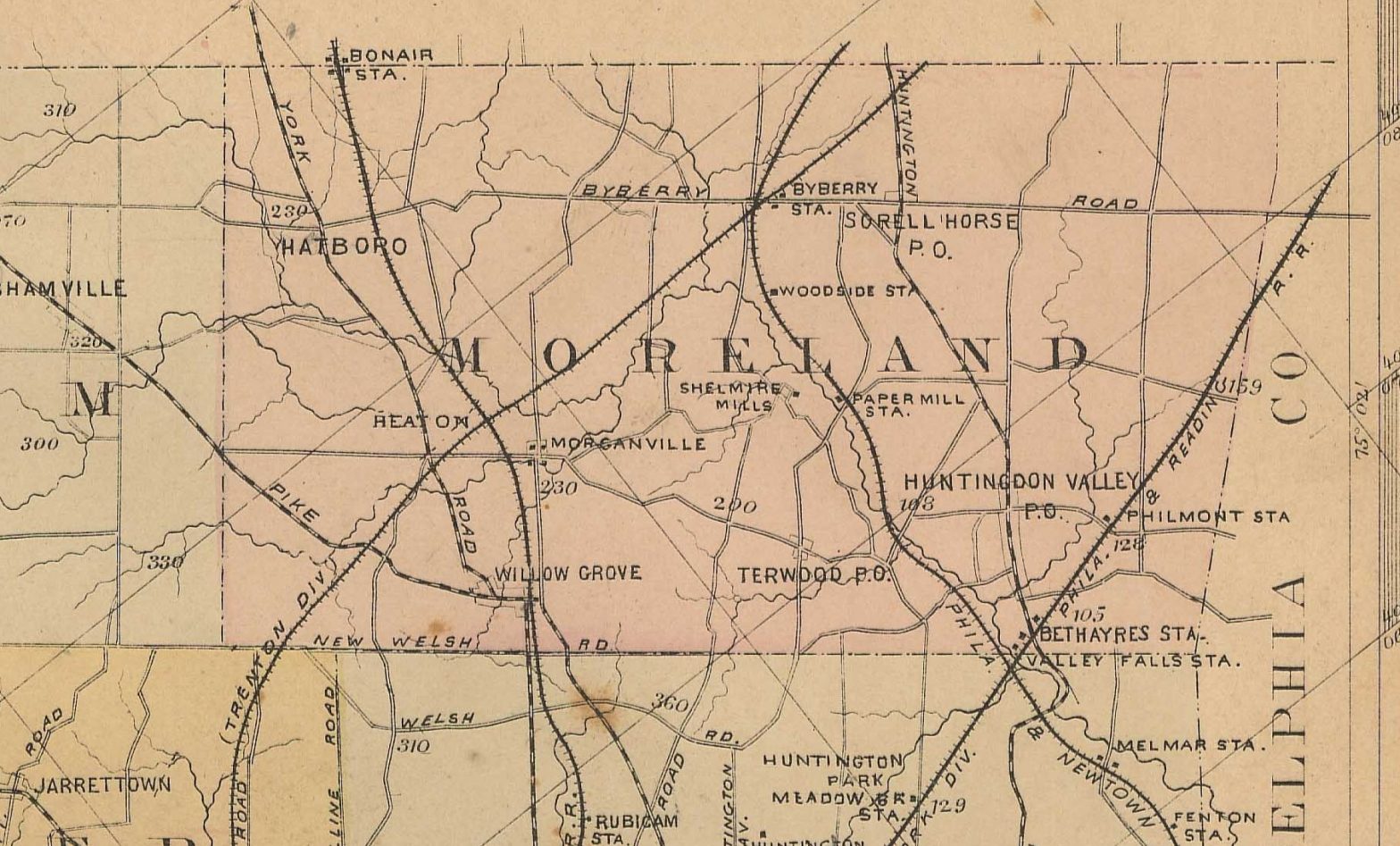

Local history even adds to one’s understanding of the present. It explains why Upper Moreland and Lower Moreland are two different townships in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania (the wealthy businessmen got into a pissing match in the early 1900s and split Moreland township). Local history explains where street names come from, why a town is organized the way it is, and how its government was formed. It answers the questions that come to mind when we’re walking down a nearby street, but that we quickly accept are too difficult to answer.

And for all the questions it can answer, local history, like all history, requires a concerted effort to preserve, and it is easily lost. A few years ago, Rowland tried to collect an archive of five area newspapers for the Old York Road Historical Society. The publisher was moving its offices, and he asked a representative if he could collect its print archives before it made the move. The representative assured him that the newspapers would be kept, and he should collect them later. But a few weeks later, he was told the papers had been thrown out in the move. All it took was one oversight, and what was likely the only existing archive of those newspapers—and possibly the most comprehensive record of the area’s history—was gone forever.

Over time, there have been many similar failures to document important information—sometimes having grave consequences, as in the case of the 1918 influenza pandemic. Due to a lack of local preservation, historians are missing important evidence like personal stories to properly analyze the sweeping impact that the 1918 pandemic had on the global population. A century later, this is a mistake archivists want to ensure is not repeated.

Because history does not preserve itself, over the past year, historical societies across the United States have documented the pandemic lives of Americans. They have collected people’s stories, photographs, and videos, creating a record for future historians. Many compare today’s moment to previous major historical events that are studied by today’s historians. Last year, Lotstein created the Yale Help Us Make History Project to collect and archive student experiences during the pandemic. Erin Garcia, director of exhibitions for the California Historical Society, told the Washington Post, “These pandemic photos and stories will become primary source material for researchers in the future studying this moment.”

Though the pandemic has intensely influenced human life in the last year, the limits of its influence should not constitute the limits of our efforts to document current human life. Local and national history alike need to be documented so that we might preserve the fullest picture of the present day.