We live in an age of Big Data. For evidence, we need not look further than the past two weeks of polling, predictions, counts, recounts, and updates as our country muddled through another election. A recent article on Forbes on the agglomeration of data by companies is full of figures beyond my comprehension: “terabytes,” “petabytes,” and “exabytes” of data that companies collect or will collect from their products. (For reference, it takes 1,024 gigabytes to make one terabyte. Petabytes followed by exabytes grow by the same order of magnitude). In 1965, an engineer named Gordon Moore claimed that our data storage and processing capacity would double every year (and later, every other year) as we created smaller and more efficient chips. Although some people have started to question how long the growth can continue, for the past 50 years, it has held true. This explosion of data collection and storage allows for innovation in self-driving cars, cancer detection, political polling (admittedly to questionable success), and much more.

As the capacity to collect and store data has grown exponentially for decades, so too have concerns about the ramifications of data collection. Today I will examine more closely one particular concern: that storing massive amounts of data might be—in and of itself—anticompetitive. Companies like Google, Amazon, and Facebook have massive troves of information on individual people as well as populations—stores that allow them to sell targeted advertisements, analyze consumer trends, and improve their products. Some regulators have claimed that these data comprise a barrier to entry into the market. While I would rather see more research into antitrust intervention for the sake of data alone, by examining Amazon’s control of multiple levels of the supply chain, we can already see how companies use data anticompetitively and thus require more careful scrutiny under our existing antitrust laws and other regulatory agencies.

At its core, the antitrust critique of Big Data is that it acts as a barrier to entry, preventing new companies from competing with established ones online. In their book, Big Data and Competition Policy, Professor of Law Maurice Stucke (University of Tennessee) and Attorney Allen Grunes (formerly at the Department of Justice’s Antitrust Division) note that “data-driven markets ‘can lead to a “winner takes all” result where concentration is a likely outcome of market success.’” As such dominant companies accumulate data, they gain the ability to “monitor emerging business models in real time…[to] identify (and squelch) nascent competitive threats.” Stucke and Grunes suggest that these market supervision practices would be considered anticompetitive except that regulators do not have the same access to data as the dominant companies and thus cannot determine when those companies act to prevent competition.

A second concern about Big Data is its privacy implications. Overwhelming majorities of Americans feel like they have only minor control over their personal data online, low understanding of how those data are used, and little ability to escape tracking by either the government or private companies. Stucke and Grunes allege that the free market does not ameliorate this dissatisfaction because it is in a state of “dysfunctional equilibrium.” Unlike in a healthy market that responds to consumer demand, in this dysfunctional one, consumers “do not believe that they have control over privacy” which makes it impossible to believe that any company will actually protect it. The lack of a competitive market allows companies like Facebook which dominate market sectors to abandon their privacy guarantees—even when those guarantees might have been the reason consumers preferred them.

While I am sympathetic to both of these concerns, critics note that concentrated data alone are insufficient to justify increased antitrust intervention and are more helpful than dangerous. As noted at the top of the column, large data sets promise great innovation and development. The centrist think tank, the Information, Technology, & Innovation Foundation (ITIF) argues that while data can be used anticompetitively, “the focus should be on abusive behavior and not on structural issues, such as how much data a company holds.” In this view, the problem of barriers to entry is overstated. For one, the network effects that lead to the concentration of data-driven markets (the trend that more users improve the service) are beneficial. We want more people to use the social media that we use because we can connect with them on it.

ITIF also notes that we ought not focus on users of online services but rather on the advertisers that fund companies like Facebook and Google and force them to compete with each other even when they do not directly compete for users. From this perspective, companies that have access to troves of data, far from wielding monopolistic power, compete with each other for advertising dollars. Further, these companies have access to the same (or at least similar) data. Data possession is replicable (or non-rivalrous), meaning that multiple entities can use the same data. Data monopolies are much harder to secure than they at first appear.

As to the concern that Big Data allows companies to keep rivals from seriously competing with them, ITIF and others allege that the market is too complicated. “Companies frequently make bad strategic decisions even when they have lots of information and strong incentives,” ITIF writes. CIO Magazine, a publication run by IDG Communications (an tech industry research organization), notes that “at some point having additional data adds no additional value,” and also that data routinely loses value over short periods of time. With the addition of the privacy lens—that companies are not adequately protecting consumer privacy as a result of their data monopoly—ITIF states that “there is no evidence that any lack of competition in providing services that feature greater privacy protections is due to entry barriers rather than a lack of consumer demand.” The Mercatus Institute goes even further, arguing that profits from using consumer data in advertising at Facebook subsidize the more privacy-intensive WhatsApp, and that breaking up the company could result in less available privacy, not more (although that argument is hypothetical and difficult to ground in the history of internet companies).

Despite their differences, both critics and proponents of scrutiny based on the structural concentration of data agree that more research is needed. Stucke and Grunes call for expanded tools for regulators to analyze the effects of Big Data, and ITIF notes that “a lack of good data” is a chief difficulty in antitrust enforcement. Although I am sympathetic to the structuralist concern for how markets are ordered—not just what consumers get out of them—the case for Big Data as a key lever in antitrust enforcement independent of other metrics requires more research. What we can do now—as both sides of the debate should agree—is look at specific applications of data in a single company and examine how data contribute to anticompetitive action.

The case of Amazon presents itself as uniquely poised to unite the two factions because it adds to the problems outlined by Stucke and Grunes and sidesteps the safeguards described by ITIF. Discovering Amazon’s antitrust violations requires no new antitrust frameworks. Unlike the company that ITIF outlined in its refute of Stucke and Grunes, Amazon is not dependent on advertising dollars. Unlike Google and Facebook, which must compete with each other to attract advertisers that comprise up to 85 percent of their annual revenues, Amazon does not depend on advertisements for money. Thus, a key check that ITIF identifies as restraining Big Data companies holds little sway over Amazon. Further, while Amazon’s market power emerges from its structure, we can fault Amazon’s actions, not just its organization.

If Big Data is the door to anticompetitive action, then the vertically-merged Amazon Marketplace is the key. Amazon collects huge troves of data on its website—tracking consumer purchases, browsing habits, and mouse movements—in order to sell as many products as possible. It is not unique in this endeavor. Amazon correctly notes that many companies sell their own brands alongside other companies’ goods (supermarkets, retailers, etc.), yet these companies do not have access to the Big Data that Amazon does, which distinguishes the company from its physical counterparts. Amazon also tracks all of the businesses that sell on its website, storing their sales data, customer attraction, and appearance in searches. The data it collects are then used to improve Amazon’s own brands that directly compete with other businesses on Marketplace. By virtue of operating as both a platform on which businesses can sell and a seller itself, Amazon can use its corporate customers’ data against them.

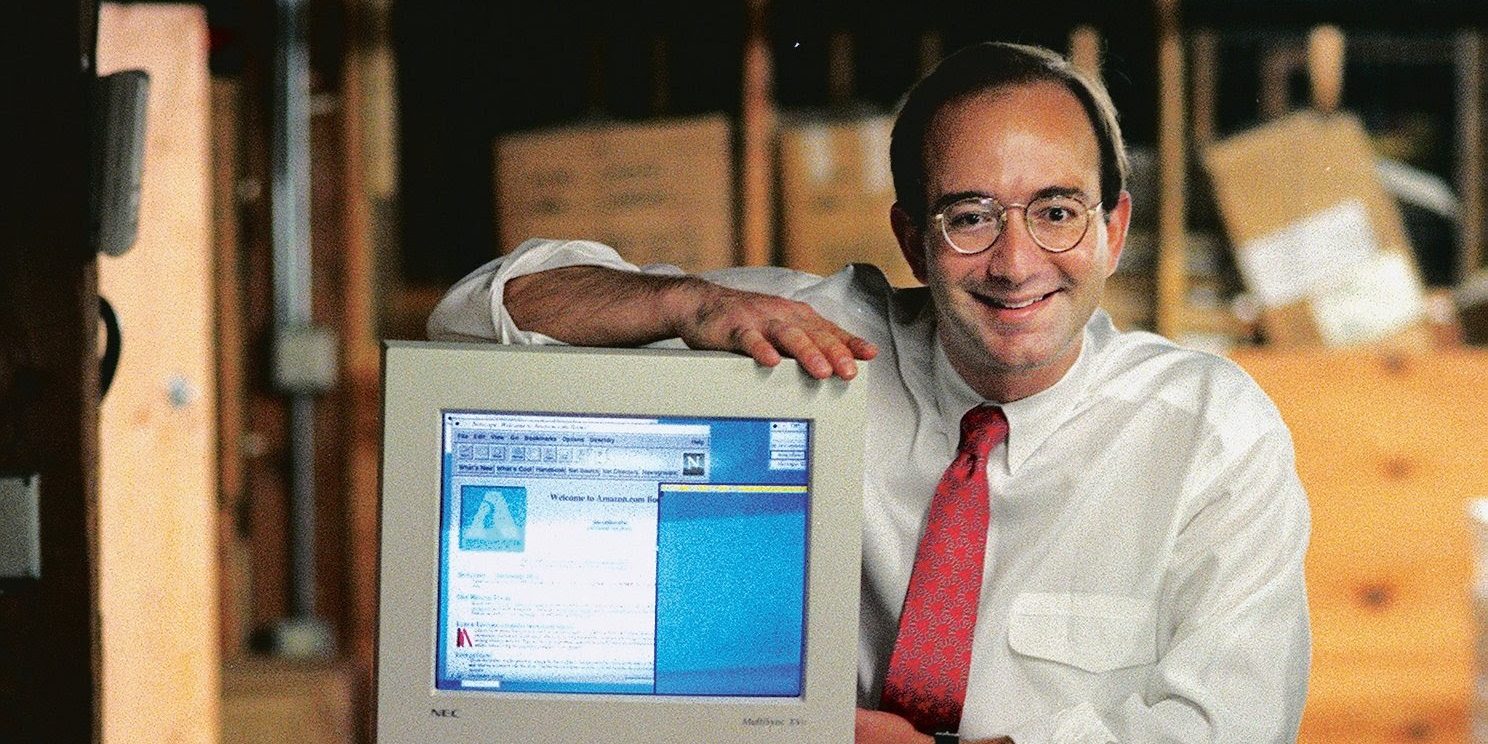

Amazon’s size only worsens the problem because its would-be competitors often cannot escape its data collection reach. Amazon Marketplace is the largest online marketplace in the world (home to 2.2 million sellers). The company captures over one in every three dollars spent online in the United States and holds the memberships of half of American households. Given its size, choosing not to sell goods on Amazon (the only way to keep the company from collecting sales data) is hardly a choice at all. Businesses as small as the notorious Quidsi and as large as Apple have agreed to sell on Marketplace. All of these data sources empower Amazon to track its sales competitors and target emerging products and companies that promise to expand or threaten its profit. Amazon itself has recognized the anticompetitive potential of its dominance of Marketplace data. It agrees in its terms with sellers that it will not pull their individual seller data for its own research and marketing, but in 2020, in a Congressional hearing, CEO Jeff Bezos admitted that he “can’t guarantee you that this policy has never been violated.”

The case of the Fortem trunk organizer exemplifies the danger. Fortem is a small business that invented a design for a set of boxes to put in the trunk of a car and began selling it on Amazon. The product was a huge success and a major seller online. Soon after, Amazon came out with its own, nearly identical trunk organizer under its label, “Amazon Basics” and began listing that item first in searches for trunk organizers. (Having an item appear first in a search dramatically increases its sales, according to one seller, by a factor of five over an item that appears in the fourth spot.) Sales of the Fortem trunk organizer plummeted. An employee of Amazon revealed to the Wall Street Journal that while the company did not run an analysis of Fortem’s business, the employee did run a report that displayed “25 columns of detailed information about Fortem’s sales and expenses.” The report instead catalogued sales of Fortem trunk organizers, 99.95 percent of which were placed on Fortem’s Amazon page. When the Wall Street Journal approached Amazon with the story, the company noted that Fortam’s trunk organizer is at the top of the list and is a bestseller on the site. It neglected to mention that Fortem now pays up to $60,000 per month to Amazon so that its products appear first.

Amazon’s exploitation of Big Data cannot be extracted from its vertically-merged status. As in the case of Fortem, the company plays both of its platforms off each other to exploit third parties. Amazon Marketplace data allowed its manufacturing arm to copy a successful product which then drove up profits for the platform by extracting advertisement dollars from Fortem to reclaim its place on the website. Nowhere in this story does Amazon enhance consumer welfare; it neither offers a better product to consumers nor a better service to other merchants. The company takes the data it gets from the small businesses it hosts and weaponizes that data against them.

The case of Amazon’s abuse of Big Data suggests that data can be a part of anticompetitive action from a company, but not that it is threatening independent of other factors. As we move forward into the world of Big Data, we must continue to rigorously advance the interests of the people over the profits of corporations, but we need not always pursue that goal through antitrust. Against antitrust action (such as breaking up the company or limiting future mergers), Amazon argues that when it used to sell its own products on a separate website from its marketplace platform, small businesses did not have as much publicity and the company’s own offerings were more limited.

Amazon’s arguments, however, have not stopped the European Commission from bringing new charges against Amazon alleging that the company uses its data to unfairly compete against the sellers on its platform. The suit argues that the data Amazon collects enable the company to manufacture the most profitable items and gain a majority of profits on the platform despite comprising a minority of sales.

The Commission’s arguments largely track those outlined in this column, with the exception that while the Commission follows Amazon’s aggregation of data, I follow the individual targeted seller. By focusing on the aggregate rather than the individual, the Commission loses a critical dimension of analysis. Through the Fortem trunk organizer debacle, we see how an actual competitor confronts Amazon’s dominance and interacts with its Marketplace that is both exploitative and profitable—a double bind, in which each competitor must either sacrifice access the biggest collection of consumers in America or surrender itself to a company that might allow it to profit but never to escape. The Commission obscures the fact that the problem is not so much that Amazon has access to massive quantities of data that allow it to adjust its production to consumer demand. Instead, it is that each byte of information comes from an individual small business that has little choice but to provide it and that faces the inescapable risk that, one day, too much success will cost it dearly. The data themselves are dangerous not on their own but only in combination with the exploitative power Amazon’s gets from having its fingers in too many pots.

That this exploitation remains hypothetical for many, if not most, of the businesses that sell on Marketplace makes it more difficult to address. The trouble with Marketplace is that it offers so much value to so many people and businesses at the price of exploiting a minority of them. Figuring out when and how to intervene is a challenge for antitrust regulators that is not new to our time, and, given the European Commission’s lawsuit, the challenges that Big Data poses might not be so severe that they require reworking antitrust law itself as much as learning how the online market demands different protections from the offline one. Thus, we find ourselves somewhere in between Stucke and Grunes on one hand and the ITIF and CIO on the other: data pose an anticompetitive threat only in the context of their use, but that use cannot be extracted from the structure of the businesses that collect them. Regulating Big Data, then, in an antitrust context, requires better analytical tools, but not a legislative adjustment to regulation itself.

Antitrust enforcement, however, is only one of the many actions that we can take to address and control the rise of Big Data in our world. Two other avenues are data taxes and increasing online protection laws. Admittedly, the data tax would require careful phrasing so as not to penalize companies for storing data in the interests of consumers (like IBM’s Watson that works on cancer diagnosis), and thus might be difficult to implement effectively. On the other hand, online protection laws such as the European Union’s GDPR and California’s CPRA both open up new ways for individuals to control their data online and provide templates for future continued regulation. For Amazon specifically, we might envision similar restrictions on the use of third party data—even perhaps closing loopholes in the restrictions to which the company itself agrees in its contracts with third party sellers. These non-antitrust solutions have the advantage of applying to all companies—not just big or notable ones—to ensure a safer internet for all people, consumers and non-consumers alike.

Even if, as I have suggested, changing antitrust law is not the first place (or at least not the only place) to regulate Big Data, we need not and ought not give up our concerns. In the wake of yet another troubled election (many parts of which were hosted on Amazon servers); the hacking of Amazon’s home surveillance device, “Ring”; Amazon’s development of facial recognition software shared with police forces; and its software that allows private companies and ICE to compile detailed profiles to track individuals through their biometrics, privacy concerns should be at the top of our social priorities. Beyond the company itself, the New York Times’s terrifying exposé of location tracking through cellphones, the authoritarian contact tracing methods that have emerged around the globe, and the disturbing accounts of social media companies in Netflix’s The Social Dilemma are all cause for alarm.

Rather than redesigning antitrust to control companies as they collect Big Data, we would be better off first deciding what kind of data anyone ought to collect and directing our government to protect us from the worst dangers of Big Data, antitrust-related or not.