Seven dollars.

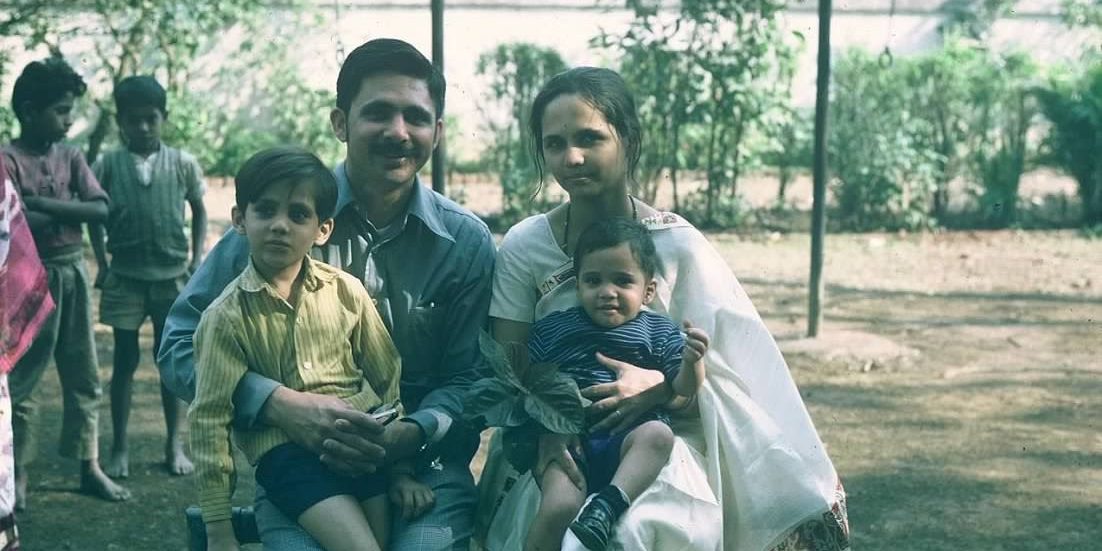

That, according to family lore, is all the money each of my paternal grandparents was allowed to carry on them when they embarked on their flight from Mumbai, India, to New York City, NY, in 1968. A byproduct of India’s rigidly protectionist “Licence Raj” era, the rule was designed to discourage emigration from India to greener pastures in the West by depriving would-be emigrants of capital. Like many an Indian policy, past and present, it didn’t work. Fresh off the Boeing, green cards in hand, a son in tow, my grandparents—whether they knew it or not at the time—had made their choice. They would be Americans.

Coming from India to Providence, RI by way of the United Kingdom, my maternal grandparents didn’t face quite the same restrictions on what they could carry when they arrived in 1973-74. “We weren’t penniless,” Ajay Dashottar, my maternal grandfather, told me in an interview. And unlike my paternal grandparents, they didn’t plan to stay forever. “I didn’t have any desire to settle down,” Dashottar said. “I just came for higher education. As a safety wall, I qualified for immigration [permanent residency] and left [for India].”

A few years later, though, he and my maternal grandmother were back in the United States, where they would end up making the same decision as my paternal grandparents: an American life.

When the COVID-19 pandemic arrived in the U.S. in full force in March 2020, both sets of my grandparents had been living in Rockville, MD, for more than 40 years—40 years of opportunities and prosperity, in their opinions, that would not have been possible in the India they left. Dashottar only retired from his job as a doctor outside of Washington, D.C. in April 2020, when the pandemic rendered him unable to work. My maternal grandmother, Pushpa Dashottar, spent decades as an organizer of events like plays and festivals in the Indian-American community. My paternal grandmother, Alaka Mangalmurti, was a clerical worker for various companies, and my paternal grandfather, Surendra Mangalmurti, an engineer who worked for years at the Washington Metropolitan Area Transport Authority, helping expand the metro lines powering the nation’s capital. “As far as my aspirations were,” he told me in an interview, “I think I have achieved [the American Dream].”

By and large, the pandemic has had a far more limited impact on my grandparents and their immigrant cohort than on many Americans. Retired, strongly health-conscious, and relatively prosperous, they’re in a prime position to wait out the pandemic. “We are getting a new experience in life,” Surendra Mangalmurti told me. My paternal grandparents have been able to garden and enjoy online bridge games with family members and friends from Potomac, MD to Poona, India. My maternal grandparents have joined COVID-19 charity drives run by Indian-diaspora community organizations. While certainly tedious, the pandemic has not upended their lives to the extent it has many others. And with luck, they’ll swiftly return to normal life when the pandemic abates.

So these immigrants, at least, are doing okay. Unfortunately, it doesn’t look like the half-century-old vision of America they represent is going to be nearly as lucky.

❋❋❋

In considering the pivotal moments that made the modern U.S., I think there’s one we often overlook: October 3, 1965. The day then-President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 (INA) was an otherwise ordinary Sunday, and the act a supposedly ordinary piece of legislation.

“This bill we sign today is not a revolutionary bill. It does not affect the lives of millions. It will not restructure the shape of our daily lives,” Johnson said at the signing, posed neatly in front of the Statue of Liberty.

He was wrong.

In the 55 years since it was signed, the INA has reshaped what it means to be an American, and redefined who gets to be one, in a way that far exceeds its creators’ expectations. Today’s immigrant population—largely Asian and Hispanic—is the product of the INA’s elimination of race-based rules that restricted immigration to the U.S. to a handful of countries in Northern Europe. The far more liberal immigration regime it introduced opened the gates of U.S. immigration to Asians, Africans, Southern Europeans, Caribbeans, and many Latinos. Were it not for that change, people like my grandparents—who were barred from U.S. citizenship until 1946—would likely have never made it to the U.S. The INA made the American Dream, the promise that you could have a better life and your children a better one than that, suddenly visceral to the majority of the world where it had long been out of reach.

In the 1970 census, taken two years after the INA went into effect, the foreign-born population of the U.S. was only 9.6 million people—4.7 percent of the population—the lowest proportion recorded in American history. In 2017, the foreign-born population of the U.S. was 44.4 million people—13.6 percent of the population—nearing highs not seen in over a century. The INA, in essence, rebirthed American multiculturalism (and thus America) after 50 years of moribundity.

That multiculturalism is now under threat. “An age of interdependence among nations” was anticipated by President John F. Kennedy nearly 60 years ago in a statement advocating immigration reform to Congress. That age reached full blast only in this century, with the rise of globalization. A key component of globalization has been the free (or freer) movement of people. The COVID-19 pandemic has brought that to an abrupt halt. A recent analysis by The Economist estimated that more than 65,000 “restrictions on mobility” have been put in place by nations around the world out of pandemic-related fears. Every country has closed its borders to some extent.

In the U.S., though, restrictions on migrants have gone beyond health precautions. The Trump Administration’s rules—like President Donald Trump’s April 2020 “Proclamation Suspending Entry of Immigrants Who Present Risk to the U.S. Labor Market During the Economic Recovery Following the COVID-19 Outbreak”, subsequently extended by Trump’s June 2020 proclamation on work visas—are clear attempts to turn back the tide of immigration that has transformed the U.S. over the past 55 years. The Migration Policy Institute, a think tank, estimated that under normal circumstances, Trump’s order would have blocked about 26,000 green cards a month. With consulates and embassies already closed and not processing visa applications, the proclamations have had limited repercussions so far—but only because the pandemic has effectively shut down global immigration to the U.S.

If the proclamations continue to be extended after the pandemic enters remission, the U.S.—which has seen the growth rate of its immigrant population shrink dramatically over the course of the Trump Presidency—could be on course for nearly no net immigration growth this year, a sharp departure from our recent history. There is a concerning possibility that even when a vaccine is found, the U.S. could follow Trump’s lead and choose insularity over openness, misjudge the real impact of immigrants, and keep its borders tightly closed. After all, there’s no justification as potent as a pandemic for xenophobic policies and politicians.

Such a post-COVID-19 America would be one truly in decline—one choosing to repudiate the path of (general) positive change that’s been charted over nearly 60 years. That’s not merely because of the diversity and heterogeneity it would lack, valuable though those are. It’s just a simple economic fact.

In medicine and as essential workers, immigrants are currently keeping America alive: 29 percent of American doctors are foreign born and over 40 percent of both agricultural and farm workers are immigrants. After the pandemic—going by 2015 trends—they’ll account for almost 90 percent of U.S. population growth until 2065, stopping the country from tipping over into perpetual old age and stagnation. Between all that, they continue to generate jobs and create businesses at much higher rates than other populations—regardless of background. If we really want to recover from the pandemic, and if we want to emerge better than we were before, a century’s worth of data on their impact suggests that more immigrants, not fewer, is the way to do it.

After all, if the work of people like my grandparents—doctors, engineers, clerical workers, community organizers—tell us anything, it’s this: immigrants—they get the job done.