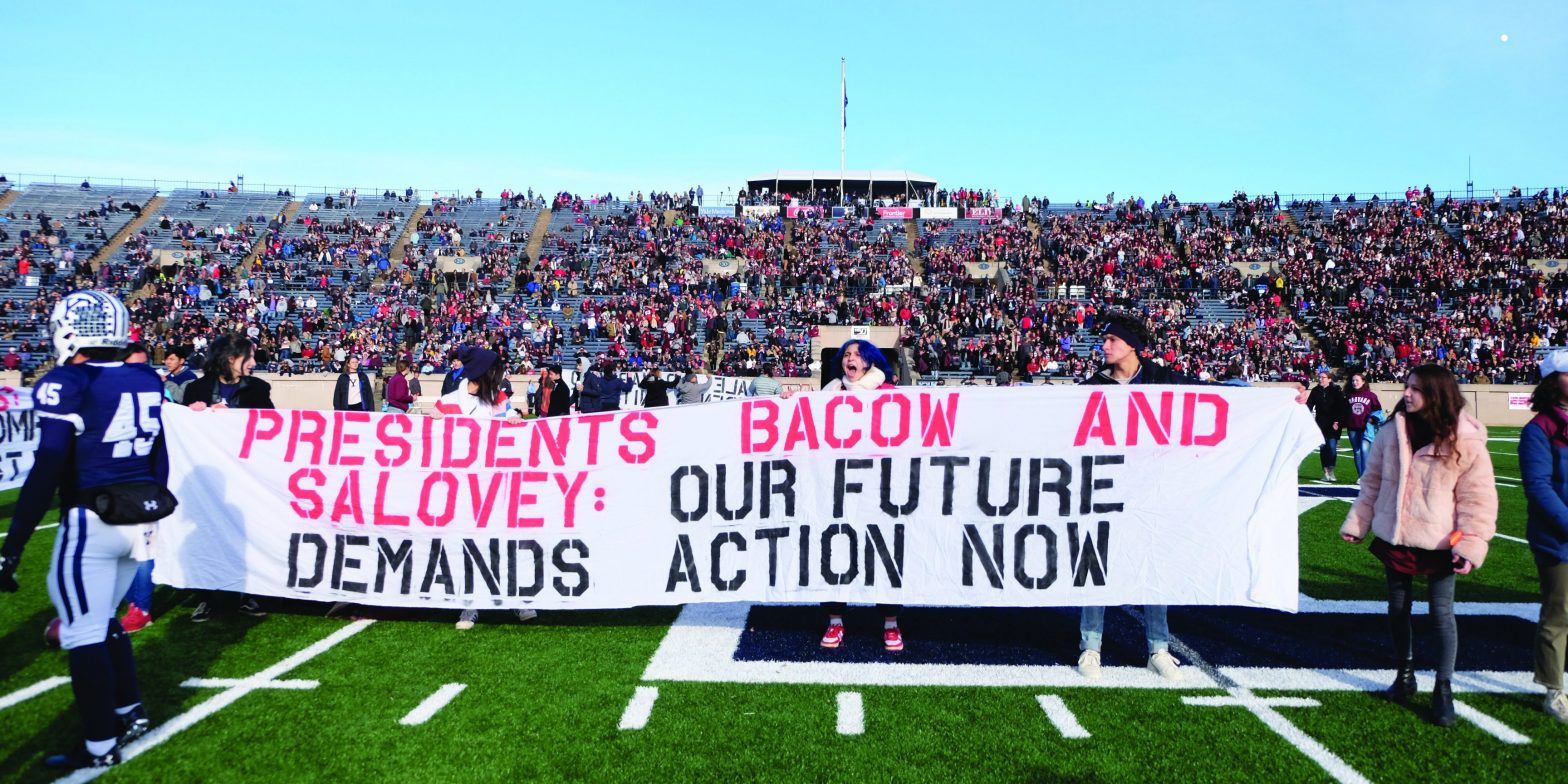

Elizabeth Juviler ‘89 first saw the news on Facebook. “Yale and Harvard students delay second half of The Game with divestment protest,” she read in the Yale Daily News, after a classmate posted the article. “It was just stunning,” Juviler told The Politic. “It was terrifically effective.”

Staring at the screen, Juviler recalled her own fight for divestment while at Yale. From nearly the moment she arrived on campus, she joined protests against investments in the South African apartheid regime, a system of racial segregation that the country’s government enforced until the 1990s. As was widely reported at the time, students worked to construct an imitation South African shantytown on the foreboding stone of Beinecke plaza.

In the weeks following 2019’s Game, discussion of the halftime protest dominated campus and drew national attention. Within hours, outlets from the Yale Daily News to conservative blogs to The New York Times (and even the Twitter timelines of several Democratic presidential candidates) buzzed about the event. And yet, the road connecting Juviler to the protesters who stormed the field is long and winding, spanning decades of Yale’s history. Only after this journey can we finally answer the essential question: How did the Harvard-Yale protest come to be?

***

Josie Ingall ‘23 had just arrived on Yale’s campus this fall when she joined countless other first-years for the annual extracurricular bazaar in Payne Whitney Gym. Amid seemingly endless rows of tables staffed by enthusiastic upperclassmen vying for her attention, she found herself drawn to one group’s poster in particular: “Climate Strike: September 25th.” Immediately, Ingall knew she wanted in. Come September, she was.

Ingall is no stranger to climate action. Speaking with The Politic, she recounted being surrounded by ongoing climate movements growing up in New York City. “I participated in Fridays for Future protests,” which she explained are modeled on the efforts of teen climate activist Greta Thunberg.

So it was a no-brainer for Ingall to get involved at Yale. She recalled, “The only club meeting I went to in the first few weeks was Endowment Justice Coalition [EJC],” one of the organizers of this fall’s Climate Strike, where 1,500 students left class to rally on Cross Campus demanding fossil fuel divestment. Ingall quickly fell in love with EJC, especially its commitment to non-hierarchical organizing. “We’re able to welcome people with open arms to an organization without an existing power structure,” she explained.

Beyond abstract policy, for Ingall and her fellow coalition members, it’s personal. Many have family members in countries that feel the devastating and direct impacts of climate change. “I remember my family sending us pictures of the smoke in the sky when the Amazon fires were at their worst,” said Ingall, whose family lives in São Paulo, Brazil. “Those pictures are so deeply terrifying.”

She had always been curious about protest. Living near the location of the 1911 Triangle Factory fire inspired her to research the ensuing labor movement. “After crisis…you gather your shit up and you organize. You make it so that this can’t happen again,” said Ingall.

She also proudly recounted the day of the September strike: “I was in a small seminar, but I was the person responsible for communicating that we were going to walk out. And all of them did.” She laughed excitedly over the phone before explaining, “I was one of the people walking around with that group banging pots and pans in the middle of the school day, feeling so at home and scared and also not knowing what the hell was going on.”

In the eyes of climate organizers, the strike was a success, yet they immediately began brainstorming how to capitalize on their growing momentum. Martin Man M.Arch ‘19 told The Politic that the 136th Harvard-Yale game in November became an obvious early target, especially because they could partner with students from another school with a massive endowment. “I think I was actually the person who first brought up ‘What about the game?’” said Ingall. In all, the protest took about four weeks of dedicated planning.

The organizers split up tasks to get the job done. “My first and most important task was bagel picker-upper,” Ingall joked of her game-day responsibility. Primarily, she acted as the group’s media liaison along with classmate Jordi Bertrán ‘23. The event was choreographed into movements of nine separate groups, each with a communications head for coordinating with other groups, a vibes captain for checking in on group members’ emotional states, and a police liaison for handling all police interaction.

The morning of November 23rd—critical bagels in tow—all participants gathered in Dwight Chapel to run through the event and ensure everyone knew their assigned roles.

Among those present was Max Teirstein ‘21, a strategy team member and communications head. Teirstein had been attending weekly meetings to discuss every possible logistic imaginable, including, “what the Yale Bowl looks like, where we would enter from, how we would enter, how we would communicate without [cell] service at the Bowl,” he rattled off in an interview with The Politic.

Come halftime, following the Yale marching band’s performance, the weeks of planning—themselves a culmination of years of activism—came to fruition. Man, Ingall, and Teirstein, in their respective groups, streamed onto the field and took their place at the 50-yard line.

***

In 1966, before any of this began, Jon Gunneman MA ‘67 PhD ‘75 followed his friend Charles Powers to an extracurricular study group. “We were looking at the impact of American corporate business in South Africa at the time of apartheid,” Gunnemann told The Politic. Through his discussions, he “became aware of the ambiguity of investing” in these companies. “What we wanted to do was to get both corporations and the government to think about this,” he recounted. “One of the principal things that came to our mind immediately was that the Yale Board of Trustees has a lot of influence.”

“The idea was to persuade the Board of Trustees to take a look at what investments in South Africa mean,” Gunneman continued. The primary target was obvious: the Board’s chairman, J. Irwin Miller ‘31.

The strategy, too, came to them quickly. “We knew [Miller] read the New Testament in Greek every morning, and we knew he read the Christian Century,” Gunnemann explained. In January, 1969, he and Powers wrote an article in the magazine calling for universities to consider their investment’s social impact.

Gunneman and Powers then wrote a formal proposal to the University, which then-treasurer John Ecklund ‘38 YLS ‘41 quickly denied in a lengthy, legalese-filled response.

This setback led Gunnemann and Powers to John Simon, a professor at Yale Law School and president of the Taconic Foundation, which was already practicing an early form of ethical investing. Together, the three met with President Kingman Brewster and the Board to rebut to Ecklund’s response.

“As we hoped, John Simon was able to take every single one of [Ecklund’s] arguments, one by one, and show that they didn’t really work,” said Gunnemann, chuckling at the memory.

Gunnemann paused to gather his half-century-old memories before recounting the meeting:

Brewster: Well, Irwin, you’ve been uncommonly quiet—what do you think about this?

Miller: Well, I sit in a chair every Sunday, the minister says something and people don’t have a chance to challenge him on anything. I sometimes think that ministers should be held accountable and responsible for what they say. What these young men are asking us to do is to be accountable for our actions, including our investments. I think that’s a good thing.

“That basically broke everything open,” Gunneman explained. The trio received a $10,000 grant to study the topic, organized a year-long research seminar, and then published a final report to the Yale Corporation, before publicly releasing a revised edition. Gunnemman concluded, “The Ethical Investor is the result of that.”

Nearly 50 years later, The Ethical Investor endures as Yale’s official guidelines on investing and the definitive source for any consideration of divestment.

***

Juviler remembers the 1985 shantytown proudly. “We had teach-ins there, rallies there, students actually slept on rotation,” she shared with The Politic. “It was one of the big movements of the moment.”

Like Ingall, Juviler cited her family as a significant inspiration for her activism. The granddaughter of socialists and daughter of two constitutional lawyers (and alumni of YLS), she recalled that her parents “went on marches with King and…for women’s rights.” In addition to her Jewish upbringing, Juviler explained how “the word equality was as close to religion as we got.”

Both she and Richard Gervase ‘89, another then-first-year involved in the protests, credited the shantytown’s visibility with attracting both campus-wide and national attention. Gervase said, “There was a physical structure on one of the most prominent places on campus.”

The shantytown quickly became a target of Yale Police, who were tasked with removing it despite fierce student resistance. “Many dozens of students were arrested trying to protect it,” said Juviler. She also recalled one particularly dramatic sit-in: “It was about 80 of us. We went in the morning, we surrounded the outside of the [investment office], and we sat down. We blocked all the entrances.”

That spring, while still a first-year, Juviler was arrested. Along with every other protester, she was detained and punished for the crime of interfering with University function. “That was kind of the point,” said Juviler, with a laugh. Ultimately, they were given a lesser sentence of an “internal mark on the record.”

With the anti-apartheid divestment protests, all roads seemed to lead to Matthew Countryman ‘86, now a professor of history and American culture at the University of Michigan. Countryman, a fifth-year senior when Juviler and Gervase were first-years, was a key orchestrator of the shantytown protest. Both explained how much they admired his leadership.

Countryman cited his own inspirations in an interview with The Politic: “My parents met in the civil rights movement. My father was white, my mother is African American.” He recalled, “We were trying to figure out how to go from a small thing to something that would affect the campus and push the corporation and President Giamatti to change their policy.”

The following fall, Yale appointed a new president, Benno C. Schmidt, Jr. ‘63 YLS ‘66. To preserve their message in this transition, Juviler and six other students—five of whom had also participated in the previous year’s sit in—staged another protest, this time inside the investment office.

As Juviler put it, “You can’t suspend 80 kids from Yale, but you can suspend five.” So with a second mark on her record, she was suspended. I could sense the wry smile as she added that it was “the same day the U.S. Senate approved sanctions against South Africa.”

Juviler’s usually carefree tone took a marked shift as she remembered how the suspension felt more like “expulsion”: “I was excommunicated.” Following a long pause, she continued: “There was never any response about that when I came back. I was wounded—I felt really burned.”

***

“We thought it was part of the halftime show,” said Sam Tuckerman ‘20, a kicker on the football team, who was warming up on the field when the protest began. “We thought it would be resolved pretty quickly,” he shared with The Politic. “But the longer it went on the more aggravated I became,” especially because the risk of injury increased as players’ muscles cooled down with each passing minute. Furthermore, he didn’t see the point: “There really is no correlation between climate change and football players.”

Following his team’s late-game comeback and eventual victory, Tuckerman penned a widely circulated op-ed in the Yale Daily News. Concluding that—even if successful—the protest wasn’t guaranteed to do much, Tuckerman explained that “the protesters didn’t value The Game itself nor the recognition Yale Football has earned over our 147 years of existence, but they opportunistically stole the spotlight that comes as a direct result of both.”

Esteban Elizondo ‘20, in a similar New York Post op-ed, compared his peers’ actions to a “childish” tantrum. In an email to The Politic, he expressed his skepticism about the protesters’ disruptive methods: “A good protest should take into account if the tactics and rhetoric are appropriate for the message and the audience you’re trying to reach.”

It is indeed unclear whether divestment would have any tangible effects. “Even if the entire Ivy League divested,” Matthew Zaft, a wealth advisor at Morgan Stanley explained, “it would have a little bit of an impact on the stock, but very, very minute in the grand scheme of things.” Unless it created a domino effect among “larger institutions” like Fidelity or Vanguard, divestment would not meaningfully impact fossil fuel companies, he concluded.

A Shell spokesperson echoed this point in an email to The Politic. He wrote, “The idea that a University divestment will accelerate our understanding of the most important issues of our time (climate change) or force a new business model is a seductive argument, but it’s not reality.”

Adele Morris, a senior fellow and policy director for Climate and Energy Economics at The Brookings Institution, amplified the problem in an interview with The Politic: “A lot of the protests and activism are…going after divestment because they’re trying to change corporate behavior, because corporate behavior isn’t being driven as it should be by public policy…. It is a tertiary issue relative to the critical role that public policy has.”

As an alternative, Morris advocates for a carbon tax—proportional to CO2 production—which directly charges companies for their pollution. “The key is to drive investment in low carbon technology and capital,” Morris explained.

Indeed, in 2014, Yale itself, through its Corporation Committee on Investor Responsibility, officially acknowledged the “grave threat to human welfare” posed by climate change but concluded that divestment was “neither the right means of addressing this serious threat nor would [it] be effective,” preferring instead to pursue change through steps like shareholder action.

President Salovey’s statement following the halftime protest adheres to a similar position, explaining that the University does not support divestment, but encourages its investors to consider the environmental impacts of companies in which they invest. Both President Salovey and Karen Peart, the Director of University Media Relations, refused multiple requests to explain what that means in practice, instead referring The Politic back to Salovey’s statement.

Reinforcing the University’s position, Zaft concluded that “for the short term,” Yale’s divestment from fossil fuel companies would amount to “really nothing at all.”

***

Despite the physical centrality of many Yale administrative offices, housed behind Woodbridge Hall’s imposing white facade, the offices’ internal workings are notoriously secretive, with small insights trickling out in carefully worded statements. Salovey’s post-game statement fits the bill exactly. Beyond offering vagaries regarding Yale’s actual investment practices, he addressed the manner of protest itself.

He wrote that “Yale has rules and disciplinary procedures that support free expression while prohibiting significant disruption of campus activities.” Here, Salovey seems to reference language from the Report of the Committee on Freedom of Expression at Yale, which stands as the university’s official policy on Free Expression, Peaceful Dissent, and Demonstrations.

The report, commonly referred to as the Woodward Report, is named after the committee’s chair, C. Vann Woodward, a Pulitzer-winning historian and Sterling Professor of History at Yale from 1961 to 1977. In May 1974, Brewster commissioned Woodward to helm a committee of 13 Yale community members and tasked them with examining the state of free expression on campus.

The report “is one of the great and enduring articulations on any campus of the benefits of freedom of expression and the dangers of suppression of that expression,” explained Floyd Abrams YLS ‘60, a noted First Amendment lawyer at Cahill Gordon & Reindel and founder of YLS’s Abrams Institute for Freedom of Expression, in an interview with The Politic.

The report articulates both that a) “Every member of the university has an obligation to permit free expression in the university” and that b) “It is a violation of University regulations…to prevent the orderly conduct of a University function or activity.”

Despite a “tension” (in Abrams’ words) between these two ideals, Peart, speaking for the University and Salovey, declined to clarify where the line is.

Nevertheless, Abrams did not take issue with the two competing rules: “In general, they can be reconciled. Speech and protest can occur and should be allowed to occur, but they can’t interfere with the rights of others.”

Importantly, the Constitution only applies to government action, not private institutions like Yale, leaving schools to enforce their own policies. Abrams ruminated, choosing each word deliberately: “Law-breaking is presumptively unacceptable,” but that, like during the Civil Rights Movement, “sometimes defiance to law is morally admirable.”

***

The divestment question comes down to three contentious words: “grave social injury.”

This language comes directly from The Ethical Investor, which calls for divestment only as a last-ditch effort. Indeed, Simon, Powers, and Gunnemann write, “Divestment, after all other corrective steps have failed, does remind us of the war movies in which the beleaguered infantryman, having exhausted his ammunition, finally hurls his rifle at the advancing hordes.” Thus, “social injury”—when companies’ actions have an “injurious impact…on consumers, employees, or other persons,” as the book says—is the key divestment criterion.

Indeed, both sides cite the same passages of The Ethical Investor as proof that they are correct. Students argue there is no harm more grave than the destruction of the planet, while the University claims that the blame is misplaced and that not all options have been exhausted. Given these competing interpretations of the same text, who can know which side is right or what the original authors intended?

“At this point, I would be tending towards yes, we should divest,” answered Gunnemann, one of the original authors of The Ethical Investor.

Gunneman also pointed to a footnote which offers “Murder, Inc.” as a hypothetical example of a socially injurious company. Yale applied this principle when it barred its external investors from investing in assault weapons sellers. Although both Gunnemann and Simon believe tobacco companies fall into the same category as well, Yale allows continued investment in them, instead supporting shareholder resolutions targeting unethical tobacco marketing.

In a follow-up email, Gunnemann considered both sides: 1) Assuming tobacco investments are unethical, “it can be argued that the harm being done to the entire planet and future generations [by fossil fuel industries] is much graver than deaths from tobacco” and 2) Fossil fuel companies do not deserve the sole blame, because “we are all complicit in benefiting from fossil fuels.”

Ultimately, Gunnemann decided the fossil fuel investments are unethical regardless. He explained he cannot ignore that “the companies…have long known the harmful benefits of their activities and have hidden the knowledge they had about the harm, lied about it to the public, and actively lobbied government to prevent governmental regulation and/or punishments.”

“Hence,” wrote Gunnemann, “the statement on p. 93 of The Ethical Investor seems to me to apply directly to them: ‘if the harm caused is grave and if there is nothing the university as a shareholder—or anyone else—can do about it in any reasonably near future, then the university should disaffiliate.’ This is where I now stand.”

***

As soon as Ingall left the field, the questions began. She quickly spoke to a few student reporters who happened to be at the game before rushing to Blue State Coffee, where she spent the afternoon and evening on the phone with publications from across the country. Later that night, on behalf of Fossil Free Yale and Divest Harvard, she also penned a widely-shared article that ran in BuzzFeed News.

Amidst the chaos, Ingall also found a few moments to reflect on the protest’s impact and her family in Brazil. “They’re very proud,” Ingall beamed. “They understand very intimately the importance of the work being done by young people in America.”

Nevertheless, Ingall has already turned her attention to planning and organizing the next climate advocacy event. She explained: “Disruption is necessary if you want people to not just go about their lives as if this is normal—because it’s not normal.”

Both Morris and Zaft gave reasons for student protesters to feel good about their work. “If Yale is pursuing climate goals at the University level,” Morris explained, “maybe it’s consistent to say, whether or not our assets would perform better from a market perspective—with or without fossil fuels—maybe this is something we should do to express our distaste for participating in a fossil fuel-reliant future.”

In Zaft’s eyes, the protest has the potential to effect real change as well. Although “the initial action of someone like Yale doing it would be very little,” he explained, “it could potentially be a domino effect that would be very big.”

In fact, according to a briefing Zaft forwarded to The Politic, investment management firm BlackRock will “exit investments that presented high sustainability-related risk, including thermal coal producers,” a move Zaft believes “could actually move the proverbial needle and could be a big domino.”

Countryman also praised the protest’s student organizers: “I’m very impressed by the planning they did, the support they got from national organizations, and the thoughtfulness with which they engaged the wider student body.” He concluded, “Business as usual is not enough.” As for Juviler, she sees much of herself in today’s protesters. When she saw the Facebook post, “I was proud to be a Yalie,” she reflected.

Ever-focused on the future of climate activism at Yale, Ingall argued, “We know that they’re listening to us. We’re very aware that they’re paying attention.” Vowing that this is far from the last time we’ll hear from her, Ingall spoke with determination: “We’re going to keep pushing.”