In January 2002, seven-year-old Sokreth Un was too young to understand why his father, Sokhom, had been run off the road by a large truck in the Odong district of Cambodia. Sokhom Un had been travelling from district to district with fellow members of the opposition Sam Rainsy Party, campaigning ahead of upcoming local elections.

It would not be the last time Sokhom was targeted for his opposition to the regime of Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen. Sokhom was a journalist who owned a paper, Proyuth, “To Fight Against” in English. One day in August 2002, Sokhom and a friend dropped off the paper at the printer around midnight, according to Sokhom’s personal statement from his 2005 U.S. asylum application, which Sokreth shared with The Politic in an email. That day, two soldiers had come to the paper’s office and demanded to speak with Sokhom, but he was out reporting.

On his way back from the printer, Sokhom noticed two cars following closely behind him. He took two or three turns to confirm the cars were trailing him—they were. His friend suggested switching cars to confuse the pursuers. The last thing Sokhom remembers is opening his friend’s car door and being struck by a vehicle.

When Sokhom awoke in the hospital, his friend told him the car that struck him was a big Mercedes driven by a man in a military uniform.

Sokhom barely survived the attack: Most of the skin on his back and arm was scraped off. He filed a complaint with the government, but the major general who ran him over claimed it was an accident. Four soldiers visited Sokhom in the hospital and expressed surprise that he was still alive.

After the “accident,” Sokhom’s family decided the brutal political violence of the Hun Sen regime made staying in Cambodia too dangerous. They moved to the U.S. in 2006, when Sokreth was eleven. Now, over a decade later, Sokreth is a student at the University of Massachusetts Lowell, which has a sizable Cambodian population. Sokreth serves as president of the university’s Cambodian American Student Association.

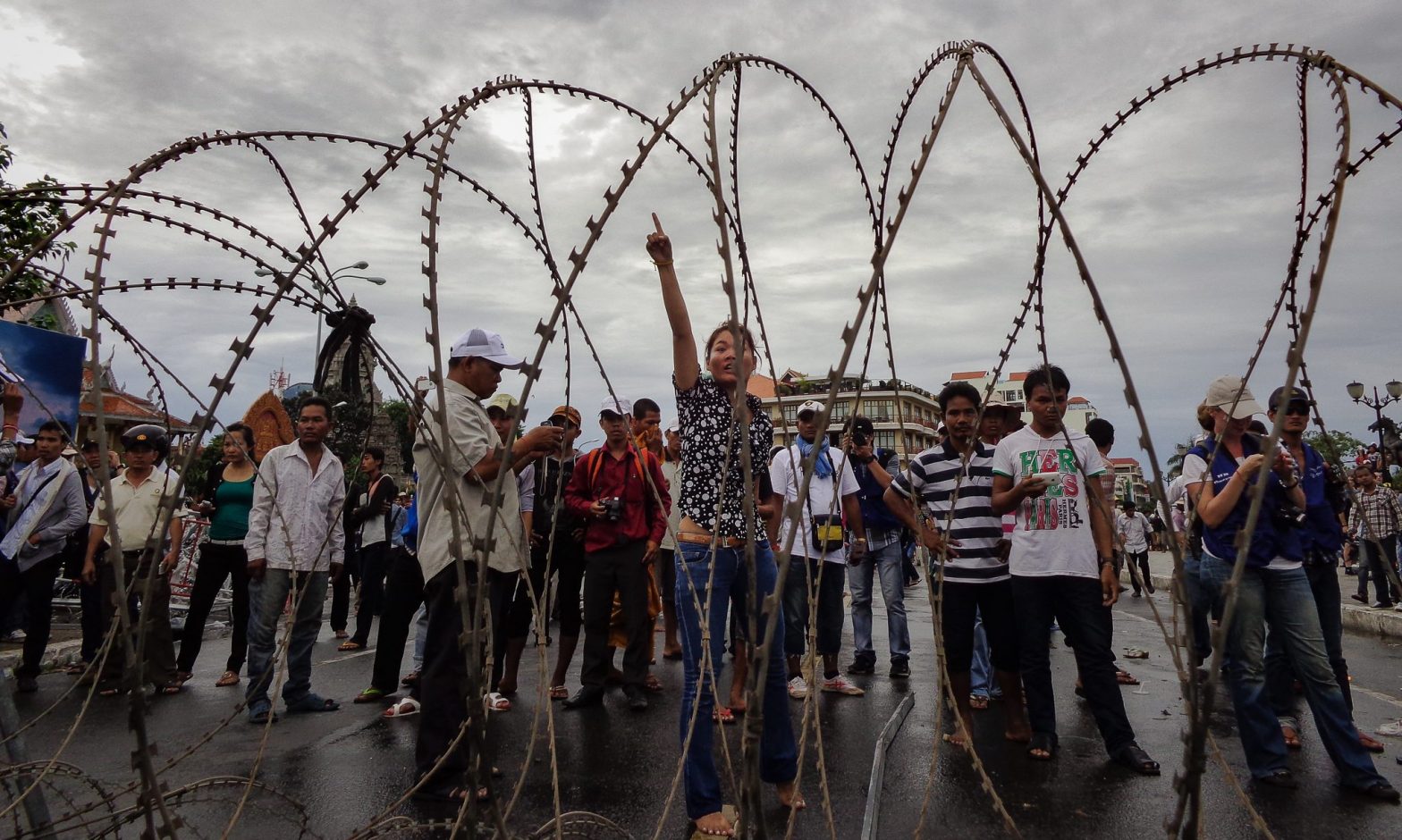

In Cambodia, Hun Sen remains in power, and his regime continues to brutally crack down on individuals and political organizations who oppose it. Hun Sen is particularly concerned with his political survival ahead of the 2018 national elections. On October 6, 2017, the regime, now approaching its third decade in power, forcibly disbanded the Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP)—the country’s main opposition party, which grew out of a merger between the Sam Rainsy Party and another anti-government group.

As Sokreth’s father experienced firsthand, news media is also considered a significant threat to the government. Cambodian journalists continue to fear repercussions from the government for publishing on sensitive issues like politics, logging, and corruption.

Hun Sen’s efforts to consolidate power have also specifically targeted institutions and publications that represent U.S. influence in the country. The regime forced the closure of independent English-language media outlets like The Cambodia Daily and U.S.-funded civil society groups like the National Democratic Institute. In August and September, radio broadcasters relaying American-funded programs were ejected from the country or forced to withdraw, stifled by excessive restrictions placed on them by the government.

“The Daily was one of a couple newspapers in town that did investigations that went out and found stories that were often pretty unflattering for the government,” Ben Paviour, a former reporter for the Daily, told The Politic in an interview. “They were stories that much [local language] Khmer media couldn’t write or couldn’t do politically because…the government would shut them down if they tried.”

Though the regime occasionally threatened the Daily with retaliation for publishing critical pieces, the recent crackdown came with an unprecedented move to shut down the paper outright. Tej Parikh, a global policy analyst and journalist, told The Politic in an email that when he was a reporter for the Daily two years ago, “There were threats, stories of aggressive encounters with officials—but nothing quite compared to the recent crackdown.”

According to Paviour, Hun Sen’s latest actions have had a chilling effect on civil society organizations, NGOs, and the press.

“They’re sensitive to the fact that they could be shut down,” Paviour said. “Anyone the government decides is part of this color revolution could be next in the net.”

Local journalists in particular fear for their physical safety. One reporter in Cambodia told the International Federation of Journalists, “Reporters talk about it being more dangerous now and there’s lots of talk of our phones being tapped. Foreigners still have an easier time working here, they might be told to leave, but for locals it’s much more difficult, especially for those with families.”

Some local journalists have even been imprisoned or denied their press cards and thus stripped of their ability to provide for their families. The IFJ report reveals that Uon Chhin and Yeang Sothearin, two former local reporters for the U.S.-funded Radio Free Asia, were arrested on November 14, 2017 on charges of “providing information that is destructive to national defence to a foreign state.” The incident highlights how Hun Sen has used ties to the U.S. to justify a crackdown on local journalists.

Meanwhile, the political opposition to the ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) has fractured. Opposition leader Sam Rainsy fled to France after a court found him guilty of defaming Hun Sen. Cambodian officials arrested Kem Sokha, the president of the CNRP, on treason charges the night before the Daily’s last day of reporting. Paviour, who helped cover the arrest for the Daily, said, “That was one of the biggest things to happen in the last year and things didn’t really slow down after that.”

What spurred this recent bout of repression by the Cambodian government? How are these attacks related to the tactics Sokreth’s father faced over a decade earlier? Understanding the crackdown requires an appreciation for the complex relations between the U.S., the Cambodian people, and Hun Sen that have defined much of Cambodia’s history since the late 1970s.

With support from Vietnam, Hun Sen’s party overthrew Cambodia’s infamous Khmer Rouge regime in 1979. But, seeking to combat Soviet influence in Southeast Asia, the U.S., China, and most of the West supported the Khmer Rouge—which had murdered two million people during its four-year rule—and other groups opposing the USSR-backed Hun Sen government in Phnom Penh. The U.S. provided diplomatic support to this resistance coalition through 1990.

Sebastian Strangio, a journalist and the author of Hun Sen’s Cambodia, told The Politic that this contentious relationship has left a “legacy of bitterness” between the Hun Sen regime and the United States.

In 1991, Hun Sen, the Khmer Rouge, and other rebel factions signed a peace treaty brokered by the United States, the Soviet Union, and China. U.S. policy officials began to lecture a government they had tried to disband for over a decade on the importance of democracy.

To Hun Sen, who remembers U.S. political intervention in support of the Khmer Rouge as well as the extensive bombing of Cambodia by the U.S. during the Vietnam War, criticism of human rights abuses by American officials rings hollow at best and hypocritical at worst. In an October 2017 speech to 20,000 factory workers in Phnom Penh, Hun Sen said, “Now, we just use the law to protect…the security and peace of our country, but they said that we violate human rights. But [the U.S.] shot, killed, and dropped bombs on our people.”

Indeed, Kosol Sek, the managing director of IKARE, a Minnesota-based non-profit that seeks to promote Khmer interests and preserve Khmer history, told The Politic that U.S. policy gives “the Cambodian people sort of a huffing and puffing-type feeling.”

In 1992, the UN launched a peacekeeping mission in Cambodia that sought to establish democratic institutions in the country. Strangio said that since the ’90s, Cambodia has been a “hybrid form of semi-democracy, in which freedoms were permitted and tolerated in certain places at certain times.”

In Phnom Penh, human rights activists contributed to a vibrant civil society, Two English-language newspapers and U.S.-funded radio broadcasts were allowed to voice criticism of the regime without much retribution. Meanwhile, local Khmer papers like the one owned by Sokreth’s father were harshly stifled.

The colorful newsstands lining the streets of the capital belied a deeply repressive reality for the majority of Cambodia’s citizens.

“The reason the government permitted these spaces to exist was precisely because they were quarantined from the heartland of Cambodia and the vast majority of the people,” Strangio explained.

The Cambodia Daily, for instance, had a circulation of just 5,000 in a country of nearly 16 million prior to its shutdown. According to Strangio, the reality of Cambodia’s free press was “tightly circumscribed by a wide range of formal and informal mechanisms.”

As Josh Kurlantzick, a fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, told The Politic when discussing the present crackdown, “Hun Sen has been using similar tactics in the past, but they have ebbed and flowed.”

Strangio pointed out that Hun Sen has justified his most recent actions as “part of a wider pushback against foreign-funded NGOs and the presence of foreign money and influence in Cambodian politics.” From the Cambodian government’s perspective, Voice of America and Radio Free Asia—two American-backed programs shuttered by the regime—are not independent media outlets at all but tools to expand U.S. influence in the country. And when speaking about the U.S.-funded National Democratic Institute, Paviour acknowledged, “If China were in the U.S. funding some sort of organization providing training to the Democratic or Republican Party, that would be a huge deal.”

Even if seen as a continuation of Hun Sen’s cycles of repression and relaxation, the closure of newspapers and NGOs and the disbandment of the opposition party constitute a much more severe crackdown than has been seen in the past. So what has caused such a harsh response?

In the last parliamentary elections in 2013, the CNRP scored an unprecedented number of seats.

“Years in power, years of wealth, have created distances between [Hun Sen] and…the struggles of ordinary people,” Strangio told The Politic. “He didn’t realize the depths of the anger.”

Though the CNRP did not enter government in 2013, it won almost 45 percent of the seats in parliament. (There is speculation that the party won even more seats than officially reported.)

Those results came despite the fact that, as Kurlantzick told The Politic, “the ruling party would use whatever levers it had to make the election not free, like not giving the opposition almost any time on TV, handing out money to CPP local party organizations, some degree of fraud, and repressing the vote in some places.”

In the past, Strangio explained, the CPP “has been able to accomodate minority opposition because having some people in parliament doesn’t really affect the networks of power that the CPP uses to maintain its hold on power throughout the country.”

The rules in Cambodia’s National Assembly are so strict that they make it difficult for minority party members to even raise concerns during parliamentary sessions.

Indeed, the CPP has commonly quashed opposition by co-opting anti-regime movements, granting their leaders political positions that lack any meaningful authority. Kurlantzick said, “It would be a typical cycle for there to be some moderation, or also co-option […] offer [opposition leaders] incentives to give up opposition and join the government in some way.”

In June 2017, however, commune elections—for local councils a level above village government—served as a wake-up call for Hun Sen. Despite the ruling party’s repressive tactics, the CNRP won a significant number of seats at one of the most grassroots levels of government. Strangio explained in an email to The Politic that opposition presence in local positions poses a unique threat to Hun Sen. “The CPP has controlled the country through political networks that extend down to the village level…This is the bedrock of CPP control.”

The CNRP victories reflected the long-held grievances of Cambodians who feel neglected and silenced by their government. Journalist Nathan Thompson told The Politic, “[The CNRP was] tapping into the general anger that people feel about the way the government operates in Cambodia. It’s generally done through a system of cronies.”

Unfair treatment under the law based on ties to government officials is commonplace.

“If there’s ever any dispute between a connected person and a not-connected person, then the connected person tends to win—which is pretty serious when it comes to issues of land rights, because this is people’s livelihood,” Thompson said.

The public outrage did not bode well for Hun Sen, who had been expecting to win handily in the 2018 parliamentary vote. Since the commune elections, there have been reports of opposition members who won commune seats being followed and intimidated into joining the CPP.

But the CPP had reason to fear that its hold on the population was slipping even before this past year.

Parikh told The Politic in an email that when he stopped reporting for the Daily in April 2016, “There was a clear sense that—with commune and national elections on the two-year horizon—the ruling Cambodian People’s Party was becoming increasingly restive, paranoid, and repressive over dissenting voices.”

Months before Parikh left Cambodia, Kem Ley, a prominent political commentator and government critic, “was assassinated in Phnom Penh under dubious circumstances.”

Another factor motivating the current crackdown could be Cambodia’s shifting geostrategy. Strangio argued that as China has emerged as a viable economic partner, “the government has been able to shrug off what is perceived to be an unwanted burden of Western demands about democracy.”

In the past, the United States and other Western nations have attempted to rein in Hun Sen’s repression and violence with threats to pull aid money. But now, those threats have less weight, since foreign aid from China accounted for nearly 36 percent of assistance received by Cambodia in 2016—almost four times the amount provided by the United States. While China is certainly not responsible for Hun Sen’s three decades of repressing his people, it has provided the regime with hundreds of millions of dollars in financial backing as it deepens its crackdown on Cambodian civil society.

Though China may be a less outwardly demanding donor than the United States, the U.S. seems to have offered little more than lip service in its calls for democracy over the years.

Strangio told The Politic that “every foreign envoy that goes to Cambodia undergoes a similar sort of pattern.”

When diplomats first arrive, they are impressed by the progress Cambodia seems to have made since the Khmer Rouge’s brutal genocide. Initial meetings with Cambodian officials prove hopeful; the regime is adept at donor-speak. Over the course of their two- to four-year postings, Strangio said, envoys become disillusioned with the mirage of democracy.

“Power functions as a function of personal relationships and not…accountable and independent institutions,” Strangio said.

Speaking on his experience living in Cambodia, Paviour told The Politic that in moments of political crisis, “Embassies, at best, put out some sort of statement…expressing grave concern…but at the end of the day, they’re there to grease the wheels for business.”

Similarly, Kurlantzick told The Politic that the EU is unlikely to follow through on a recent threat to revoke trade preferences, which are currently a boon for Cambodia’s economy.

“They have to balance a desire for really holding Hun Sen accountable with the fact that the significant effect would probably make a lot of people who are relatively poor even poorer,” he said.

Germany has suspended preferential treatment in issuing visas for private travel by Cambodian government members, but has held back on more sweeping sanctions.

So what can Cambodia’s opposition expect? Recent jailings and past political violence have stoked fears among those who seek more democratic representation.

Sek told The Politic that his family and friends living in Cambodia “are very reluctant to answer questions related to politics” out of fear.

“This community has just woken up from a recent genocide in the ’70s and ’80s,” he said. “So there’s a significant amount of wounds and damage that…includes fear factors and suspicions.”

It is possible that after Hun Sen secures a now-certain victory in the 2018 elections, he will decide it serves his political interests to let the CNRP reestablish itself under strict government control.

Kurlantzick said there may be “some sort of sham moderation of behavior before or after the election.” Still, it is unlikely that the regime would allow the CNRP to enact meaningful change in Cambodia.

History has shown Hun Sen’s tendency to fluctuate between repression and superficial relaxation, but Strangio told The Politic, “The baseline trend is moving towards more repression, and more permanent forms, a new status quo.”

Paviour concurred.

“Generally these things tend to happen in waves…but this seems to be chugging along,” he said. “I don’t think even Hun Sen knows where it’s going to end.”