A body was found floating in the Chubut River on October 20, 2017. The river, slow-moving and shallow, runs through the Patagonia region in southern Argentina. Its name comes from a word in the Tehuelche language that roughly translates to “transparent.” In the previous two months, the waters had been searched three times.

On that day in late October, the authorities finally found what they had been looking for—and what the nation had been asking for. His name was Santiago Maldonado, and he had been missing for 78 days.

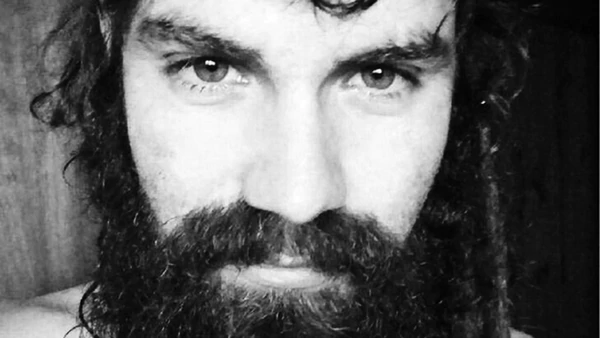

Three months earlier, on August 1, Santiago Maldonado was at the Lof de Cushamen, a camp not far from the Chubut River. The base was set up by activists to demonstrate in support of the land rights of the indigenous Mapuche people. Santiago’s face, dominated by a long, scruffy beard, was hidden under a hood; he, along with seven other protesters, blocked the National Route 40 highway. The Argentine Gendarmerie, an elite police force under orders to intervene, disrupted the protest.

When the police started firing rubber bullets and launching stones, Santiago fled with other protesters into the forest and the nearby river. A young demonstrator stated in his trial that he and Santiago were running together when he suddenly lost sight of Santiago. Shy and scared, the demonstrator told the judges that he had last seen Santiago alive in the hands of the gendarmerie.

Santiago Maldonado went missing. Over the next two months, his name became a charged, political anthem. Social media erupted in indignation and his picture was plastered on sidewalks, bus stands, and government buildings, accompanied by the words, “¿Dónde está Santiago Maldonado?” [Where is Santiago Maldonado?]

The case gripped the nation, making its way into even the most unlikely of arenas.

“In schools, in classes with children as young as ten years old, teachers would conduct roll calls and would repeat the last name Maldonado in order to make a political statement, as if to press the question of where he was…the same goes for waiting rooms in hospitals,” said Adrian Bono, CEO of the Buenos Aires-based digital media company, The Bubble, in an interview with The Politic.

On October 1, more than 3,000 people assembled in the Plaza De Mayo in Buenos Aires to demand that Santiago be found.

“¡Ahora, ahora! Resulta indispensable, justicia por Santiago, el gobierno es responsable,” they chanted.

[Now, now! It’s indispensable, justice for Santiago, the government is responsible.]

Forced disappearances are rare in Argentina today, but the slogan reminded many of Santiago’s compatriots of a not-too-distant past. After a 1976 coup, a right-wing military junta controlled Argentina by brutally repressing dissidents. One of the most infamous (and popular) methods used by the regime’s death squads was to sedate resisters and drop them from planes into bodies of water.

Once Santiago’s corpse was found floating in the Chubut River, the nation tensely awaited the results of the autopsy and any other relevant information from the government of President Mauricio Macri. Santiago Maldonado, a previously unknown tattoo artist from the small town of Veinticinco de Mayo, was to become the barometer of Argentina’s democratic progress.

***

For Argentines who remember the old junta rule, distressing memories have resurfaced with the disappearance of Santiago under Macri’s conservative administration. Nearly a quarter century has passed since the military junta fell from power. Beginning in 2003, a socialist couple, Néstor and Cristina Kirchner, each served as president of Argentina successively. But the hegemony of leftist Kirchnerism ended with the 2015 election of Macri, who identifies with the center-right.

Bono from The Bubble emphasized that the Argentinian right should not be equated with its American counterpart.

“Center-right here means a government that still does believe in climate change and supports marriage equality,” he told The Politic.

But the memories of the junta still worry Argentines who consider the current government conservative. Beatriz de Lezica, National Director for Argentina’s Ministry of Culture, told The Politic in an interview: “We are all a little bit traumatized,” and, referring to the NGO founded in 1977 to find people abducted at the hands of the military dictatorship, added, “the Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo are completely entitled to feel trauma because they saw the loss of family and people close to them, but even those people like me who were quite small, I am also quite traumatized. We are afraid of violence.”

As the case unfolded, Argentina prepared for its midterm elections, and Cristina Kirchner, as an opposition leader running for a Senate seat, called out Macri for his apparent apathy towards Santiago’s disappearance. In an interview in September, Kirchner reminded the nation of her and her husband’s response to the 2006 disappearance of Jorge Julio López, who went missing after testifying in the trial of a junta-era police commander.

“Néstor spoke to the country about Jorge Julio López immediately; it has been 43 days and we did not hear a single mention about Maldonado from Macri,” said Cristina Kirchner.

Many interpreted the president’s silence as evidence of a guilty conscience. To those protesting Santiago’s disappearance, “El gobierno es responsable” was not only a call for accountability but an expression of alarm that Macri’s administration may not be in line with democracy.

Activist groups played a key role in rallying awareness of Santiago’s case. One of these groups was established during Argentina’s junta rule: the Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo. They helped organize the October 1 rally where demonstrators accused the government of having a hand in Santiago’s disappearance.

“The city of Buenos Aires had three or four rallies, the most important one was at the Plaza de Mayo…3,000 people is a lot in our country,” said Alan Iud, the coordinator of the NGO’s legal department, in an interview with The Politic. “There were demonstrations in most of the major cities in Argentina.”

The Grandmothers confront the ugly aftermath of the junta on a daily basis and the organization is anxious that Santiago’s disappearance might mark the return of repressive policing in Argentina.

Iud, awaiting the final results of Santiago’s autopsy, told The Politic: “Even if it turns out that he was not taken into custody, there is still the responsibility of the security forces.”

“One case is worse than the other, but we need to understand that these kinds of deaths and these kinds of disappearances are not possible under a security force that works well,” he continued. “There is a responsibility of the police in this disappearance of Santiago that demanded two months to find his body.”

Amid the tension ahead of the midterm election, the disappearance became a significant campaign issue.

This anxiety manifested itself during Santiago’s autopsy, de Lezica said.

“We didn’t trust the justice [system]. Nobody was allowed to touch the body until there were specialists chosen by the family, by the Abuelas [Grandmothers], by the government…there were fifty-five experts that travelled with the police as they took his body from the river. In the autopsy room, nobody was allowed to perform without all fifty-five experts being in the room,” de Lezica explained.

But even before his dead body was discovered, Santiago had acquired a transcendent quality. As the Grandmothers said in a public statement: “For him, for his family, for the future, we say memory, truth and justice.”

***

On October 22, Argentina midterm elections took place—just two days after Santiago’s body was identified. The results were unexpectedly in Macri’s favor. While he was unable to get an outright majority, his supporters picked up key seats in parliament. The result shocked Kirchnerites and those who had turned out by the thousands to protest Santiago’s disappearance.

Santiago’s story now required a new narrative: How did an “undemocratic” administration under which a man went missing harness the support of the Argentinian people?

Bono had a simple answer.

“I’m going to say something very politically incorrect,” he told The Politic, “but I believe that the Argentinian people didn’t actually care at all about Santiago’s disappearance.”

The autopsy did little to solve the mystery surrounding Santiago’s death: It found that Santiago had drowned and that his body had been in the river for the entirety of the two months since he disappeared.

The results were up to political interpretation. To Macri’s supporters, Santiago drowned—as his family confirmed, he could not swim—in an attempt to escape the Gendarmerie. But to others, Santiago had been taken by the police and his body was later dumped in the river. His blood, therefore, was on the authorities’ hands. “Santiago’s was a case that showed how divided Argentinian society was,” said de Lezica.

This second narrative fits with the theory of a targeted assassination, but one key question remains unaddressed: Why Santiago? If Macri’s government had plotted Santiago’s disappearance and death, why did they choose him and not any of the other seven protesters blocking the highway that night?

For Bono, the answer is no reason at all.

“I’m on the fence over the fact as to whether he may have been taken by the border patrol,” Bono said. “But to go out and say that the president ordered the assassination of a guy that he didn’t even know or hadn’t even heard of before—like, he wasn’t a leader of a violent group, he was just a guy who decided to join a protest that day—and to use that to have a large part of the population come out and say that the dictatorship is back is insane.”

Bono argued that leftists’ labeling of Macri’s government a dictatorship is “only pissing people off more and this is my fear.” He continued, “This is why Donald Trump won in the United States. My fear is that people are taking things to such an extreme the average Argentinian will no longer consider Macri right-wing enough in 2019.”

He quoted his mother as an example of a Doña Rosa—the Argentine equivalent of the Average Joe. “[My mother] said, ‘Enough with the human rights bullshit.’ The Macri administration sucks at handling or cozying up to human rights activists not because they are against human rights but [because] they feel that Cristina Kirchner has made such a crusade of human rights,” Bono explained.

But De Lezica believes that Santiago’s prior anonymity is exactly why his case has caught the public attention.

“He was a boy at the wrong place at the wrong time. They were not targeting him,” de Lezica said. “He was an artisan, he made tattoos and he decided to join a protest that day.”

De Lezica has a son who is nearly the same age as Santiago. “It could have happened to anyone,” she said.

It is unlikely that anyone will figure out what exactly happened to Santiago. In the absence of definitive evidence, his death has become a persuasive device for telling two divergent stories.

“We are living in a post-truth world where you believe what you want to believe,” said Bono. And in this world, Santiago Maldonado has disappeared. What replaces him is a version of a man, with his face and his name, who transforms to align with the agendas of those who use him. To some, the new Santiago—a martyr—is a symbol of Argentina’s future. But the real Santiago Maldonado, the tattoo artist from Veinticinco de Mayo, has been lost, submerged under the waters of the Chubut River.