Deep in the forests of New Hampshire, oaks and maples fall by the hundreds. Logging is not uncommon in these parts, but it is not usually done to support an Ivy League endowment. To the tune of buzzing chainsaws, Yale trades forests for lucrative returns.

Over the past 20 years, Yale has quietly purchased over 10,000 acres of forests that sprawl across New England. Rather than relying exclusively on traditional stocks, Yale’s current Chief Investment Officer David F. Swensen has chosen to invest part of Yale’s endowment in unorthodox assets, including natural resources. In the last few years, the pace of logging on Yale’s land has increased dramatically. As the felled trees pile up, the question emerges: Is the university ignoring its commitment to environmental sustainability for the sake of higher returns on its endowment?

Swensen is hailed in investment circles for his pioneering investment strategy, which has elevated Yale’s endowment to 25.4 billion dollars—the second largest of any university in the world. Yale’s forest holdings are a crucial part of this success. They offer stable yields that have protected Yale from unexpected economic shocks, like the 2008 Recession. Over the past 20 years, the asset class has generated an average yearly return of 16.2 percent, compared to the 9.3 percent average yearly return on more traditional investments.

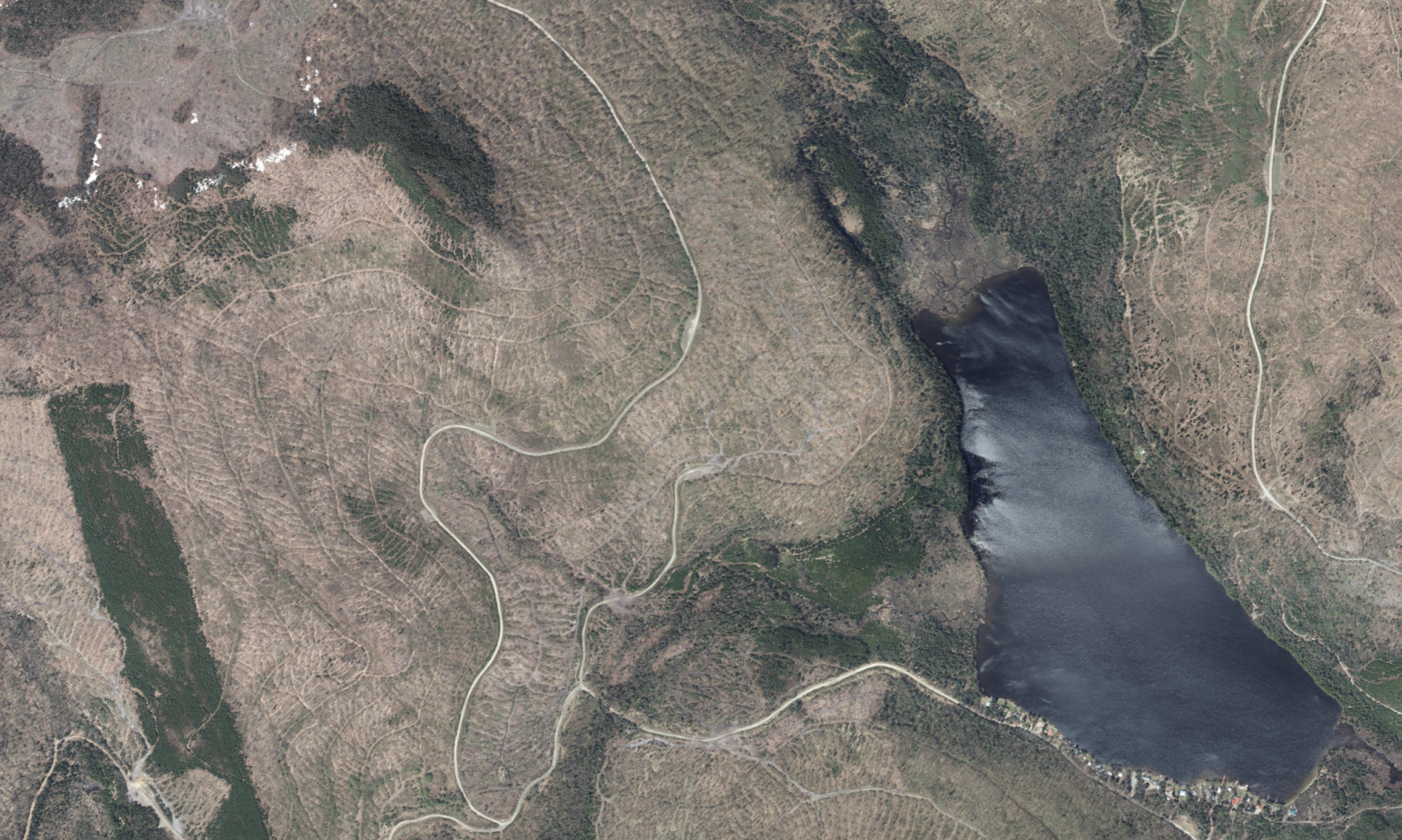

Yale does not oversee its forests directly, and instead contracts the work to a company called Wagner Forest Management. Among other administrative duties, Wagner is responsible for logging portions of the forest to collect marketable timber. But over the last four to five years, Wagner has become increasingly aggressive in its forest management strategy, clearcutting large swathes of Yale’s forests.

Wayne Montgomery, the former owner of a logging company and a 40-year veteran of the forest industry, told The Politic that this increase in logging activity is a result of Yale’s push for higher returns on its investment.

“I think part of their plan is to look at a 13 to 15 percent return on investment. But to do that on timber land you’ve got to be very, very aggressive in your management, and you have to throw sustainable forest management out of the window to accomplish that,” he explained.

While “sustainable logging” might seem like an oxymoron, the practice is possible when done correctly. A forest can be kept healthy—and turn a profit—if the tree population is kept constant and only the excess growth is felled for timber each year. But according to Rick Samson, commissioner of Coös County, New Hampshire, where Wanger manages a Yale forest, the company seems to be ignoring these principles.

“I think what they decided is the best way they can maximize their investment is to liquidate the lumber and then try to find easements to take their place,” Samson told The Politic. “My fear is that once they liquidate the lumber, it will be 50 or 75 years before there is any marketable lumber grown there again to sell.”

Yale has no such fear. In a July 2017 Statement, the University said that Wagner Forest Management “practices sustainable forest management on the Bayroot LLC lands in conformance with certification standards promulgated by the Sustainable Forestry Initiative (SFI) and the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), as confirmed by independent auditors.”

Clear-cutting the forest also has implications for the local economy.

“The only people that would be interested in buying that land and could afford to sit on it for 50 to 75 years would be the federal government, but the federal government would use our tax dollars to buy that land…and it’s taken out of the tax base,” Samson said. “So it appears to me that Yale’s concern is their bottom financial line and their endowment, not the benefit of the county and the local communities.”

While Wagner Forest Management has clear-cut certain tracts of Yale’s property, it has left other stretches of forest intact. According to Samson, Wagner practices sustainable forest management and selective cutting in those parts of the property, in order to maintain its image.

“Those are the portions that they show reporters and the organizations to say they’re sustainably managing the land,” Samson said. “However, they do not go on the property where they clear-cut and there’s nothing left.”

According to the Sustainable Forestry Initiative website, forestland owners meet an array of environmental standards in order to receive certification from the Sustainable Forestry Initiative. The Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) similarly requires an independent auditor to verify that forest managers meet criteria in several key areas: compliance with laws and FSC principles, indigenous people’s rights, community relations and workers’ rights, environmental impact, and maintenance of high conservation value forests.

But Montgomery and Samson are skeptical of how much these certifications and sustainability standards really protect the forests.

“The FSC program is one that really looks at their management plans and determines whether their management plans are being adhered to. That’s not to say they’re looking at sustainable forest management,” Montgomery said.

“FSC doesn’t get into whether it’s a good idea or not, they just say, okay, did you meet the terms of your management plan? And that could mean they could be clearcutting everything in sight, but it’s not FSC’s job to evaluate whether or not they’re practicing good forestry.”

Samson also believes there is a conflict of interest between logging companies and certification firms.

“Those two organizations are paid by Wagner to come in and do a report,” he said. “They are not gonna come in and give them a bad report…because of course, if they do, they are not gonna get hired back.”

Sophie Freeman ’18, former president of the Yale Student Environmental Coalition, believes other forms of oversight are needed.

In an email to The Politic, Freeman wrote that “Wagner Forest Management should, at the very least, comply with forest sustainability standards as recommended by the Yale School of Forestry. Yale students, both undergraduate and graduate, have expressed their strong opposition to the lease and believe that Yale is acting in direct opposition to its professed values.”

Criticism of Yale’s forest management is not limited to its logging practices. On July 1, 2017, Bayroot LLC, the Yale-owned company that controls Yale’s forests, approved a plan to build a hydropower transmission line across a 24-mile strip of Yale-owned forest. The line would carry hydropower generated by plants owned by Hydro-Québec, a Canadian energy company, from Quebec to New England.

In an April 2017 article for the Yale Daily News, Freeman criticized the proposed plan for its potentially harmful environmental impact.

“One of the core tenets of the Yale Sustainability Plan 2025 is to ‘plan and preserve resilient and sustainable infrastructure and landscapes,’” she wrote, “Yet can Yale really claim to be committed to sustainability if it controls a company which directly subverts this principle?’”

Samson opposed the program, too, and sent Yale a letter attempting to persuade Yale to terminate the deal.

“This university is on the verge of undermining the widespread and heroic conservation efforts in our county by leasing a 24-mile strip of land that is necessary for the development of Northern Pass,” Samson wrote.

The University issued a statement in response to the growing opposition.

“Institutional investors such as Yale typically invest with managers through partnership arrangements that limit the investor’s ability to control decisions from both a legal and best practices perspective,” the statement read. “Wagner Forest Management did not have the ability to terminate the option to renew under the terms of the lease.”

Samson said that he remains unconvinced. “If Yale owns the land, and they hire someone to manage it, and they are not managing it the way it should be, there is no doubt in my mind that Yale could either have them manage it properly or get someone else to manage it.”

Montgomery said he believes Yale has the power to terminate the deal.

“These people are some of the greatest business minds in the world running this endowment,” said Montgomery. “Do you think they’d put themselves in a situation where they didn’t have an out if they needed it?”

Currently, the Northern Pass hydropower line project is undergoing a New Hampshire Site Evaluation Committee hearing that has dragged on as testimony continues to trickle in from all sides of the debate.

The potential environmental risks of the pipeline, if approved by the committee, are severe. The pipeline would cut through the Great Northern Woods and the White Mountains, areas that contain some of the largest tracts of forestland in New England. According to the Appalachian Mountain Club, 90 to 140 national and state scenic viewpoints would be impacted by the route.

The Hydro-Québec project could contaminate many of the natural resources that the Pessamit Innu First Nation relies on, such as the population of salmon in the nearby Betsiamites River.

In the face of these threats, local communities are fighting back. Of the 32 towns in the project’s area of impact, 31 voted to oppose the project, and the people of the Pessamit Innu First Nation have testified at the Site Evaluation Committee hearing in an effort to preserve their rights to resources. Coös County farmers refused huge offers for their land, choosing instead to forgo the money and obstruct the development of the project.

Yale, Samson believes, could fight back, too. By using the university’s influence to stop the progress of the Northern Pass project, Yale would correct its previous failure to commit to sustainability and responsible investing.

The window to act, he said, has not yet closed: “I do believe that they could do the right thing.”