“I hereby reject the results in totality. Let me repeat: I will not accept the results based on what has happened.”

More than a few American political pundits thought Donald Trump might have made a statement like this had he lost November’s presidential election.

But the contested vote in question actually occurred on December 1, 2016, in the Gambia, mainland Africa’s smallest country. And the rejection of the results, announced on state television, came from Yahya Jammeh, the strongman who had been president of the Gambia for twenty-two years.

Bizarrely, Jammeh made his declaration on December 9, a full week after he publicly–and given his authoritarian reputation, perhaps unexpectedly–conceded defeat in his country’s presidential election, calling to congratulate opposition candidate Adama Barrow on a victory few had seen coming.

In a 2011 interview, Jammeh told the BBC, “I will deliver to the Gambian people and if I have to rule this country for one billion years, I will, if Allah says so.”

One could be forgiven for thinking he meant it literally. Prior to this year, Jammeh had won four elections, although most were deemed unfair by the opposition and international observers.

Jammeh’s grip on power did not start and does not end at the polls. He ascended to the Gambia’s presidency in a 1994 coup d’état, and has been regularly accused of using brutal tactics to silence opponents.

“President Jammeh and the Gambian security forces have used enforced disappearances, torture, intimidation, and arbitrary arrest to suppress dissent,” said Babatunde Olugboji, Deputy Program Director for Human Rights Watch (HRW) in a 2015 video about the Gambia.

An Amnesty International report released earlier this year highlighted dozens of cases of incommunicado detention without charge for six months or longer in 2015 alone, stating, “Some of those detained were tortured at the [National Intelligence Agency] headquarters, including with beatings, electric shocks, waterboarding or being detained in confined holes in the ground.”

In the HRW video, an imam arrested in 2012 for speaking out against executions recalls, “Every day, [the security forces] pulled me out of the cell, took me somewhere, beat me for two, three hours. Every day. Until nine days, the ninth day they took me to a big hole like a grave, they put me there and they covered my body with sand up to my chest. And they said, ‘Now it’s just to complete, to bury completely if you don’t tell us the truth.’”

Prior to the country’s 2011 presidential election, Jammeh told reporter Umaru Fofana, “When they talk about rights and rights, human rights, freedom of the press…this country is a hell for journalists.”

Many journalists agree. State media in the Gambia is tightly controlled by Jammeh’s government, and fear of violent retribution keeps most independent journalists from voicing criticisms of the administration.

According to the Doha Center for Media Freedom, over a hundred Gambian journalists have fled the country over the course of Jammeh’s rule. Those who stay and rebel have faced harassment, arbitrary detention, death threats, arson attacks, and in the case of The Point newspaper’s Deyda Heydara, murder.

In the BBC interview, Jammeh said of his critics, “I will not bow down before any human being except the Almighty Allah. And if they don’t like that, they can go to hell.”

Jammeh has also had harsh words for LGBTQ Gambians, demanding in 2008 that all homosexuals leave the country or face beheading. (Six years on, his view had not meaningfully changed).

Around the same time, Jammeh claimed to have developed a herbal cure for AIDS. To the alarm of doctors, he asked patients on whom he tested the treatment to stop taking antiretroviral medications.

Before this year, Jammeh–officially His Excellency Sheikh Professor Alhaji Doctor Yahya AJJ Jammeh Babili Mansa–was generally able to quash challenges to his rule. A failed coup in December 2014, for example, involved approximately ten people trying to storm the presidential palace while Jammeh was abroad.

But 2016 brought a new and more difficult test for Jammeh, starting with a nonviolent protest in April in the country’s largest city, Serekunda, that was organized in part by Solo Sandeng of the opposition United Democratic Party (UDP). Sandeng was arrested at the march, then tortured to death.

Sandeng’s daughter Fatoumata, who is now in exile, told HRW, “It’s not a new thing in the Gambia, that people get killed by the government and they don’t even admit that they have killed anyone.”

Sandeng’s case, however, jolted the opposition into action. Among the 90 people detained at UDP-led demonstrations over Sandeng’s death was the party’s longtime leader, Ousainou Darboe.

With Darboe–Jammeh’s strongest challenger in each of the Gambia’s four previous presidential contests–in prison, Jammeh must have thought winning a fifth election would require minimal effort.

But there was widespread discontent over the state of the Gambia’s economy, largely dependent on peanut farming and tourism. Along with Jammeh’s repressive regime, the country’s youth unemployment rate of 38 percent is a major driver of migration to Europe, which almost always involves a risky Mediterranean crossing.

The Torch newspaper reports that over 11,000 Gambians applied for asylum in EU countries last year. But in recent months some, including a famous footballer and a popular wrestler, have not been lucky enough to make it that far.

Public anger–particularly among young people–combined with encouragement from the vehemently anti-Jammeh Gambian diaspora to sustain and unify the opposition. In September, the UDP and six other parties jointly nominated Barrow as their presidential candidate.

Barrow is a real estate mogul who has never previously held elected office. One newspaper supporting him even admitted, “Until his selection as the presidential candidate…little was known about Adama Barrow.”

Despite Barrow’s lack of name recognition, the opposition remained confident that his personal qualities and platform for change would carry him to the presidency. (After the election, the British press became captivated by the fact that he worked as a security guard in London while studying for his real estate license.)

“He is a humble, kind, and industrious man who breaks the deal. He is down to the earth,” one UDP leader said of Barrow to Kairo News. His campaign centered on promises to respect human rights, media freedoms, and judicial independence. He pledged to serve no more than three years as president and introduce a two-term limit for the office.

Barrow had little sympathy for Jammeh, remarking upon his nomination, “In the coming days, my fellow Gambians, I will be stretching my hands to come together and form a single front to once and for all take this soulless dictator out.”

Barrow favored reversing Jammeh’s December 2015 decision to declare the country an Islamic republic. Further, he stated his intention to have the Gambia rejoin the Commonwealth of Nations and the International Criminal Court, organizations that Jammeh had decried as neo-colonial and racist, respectively.

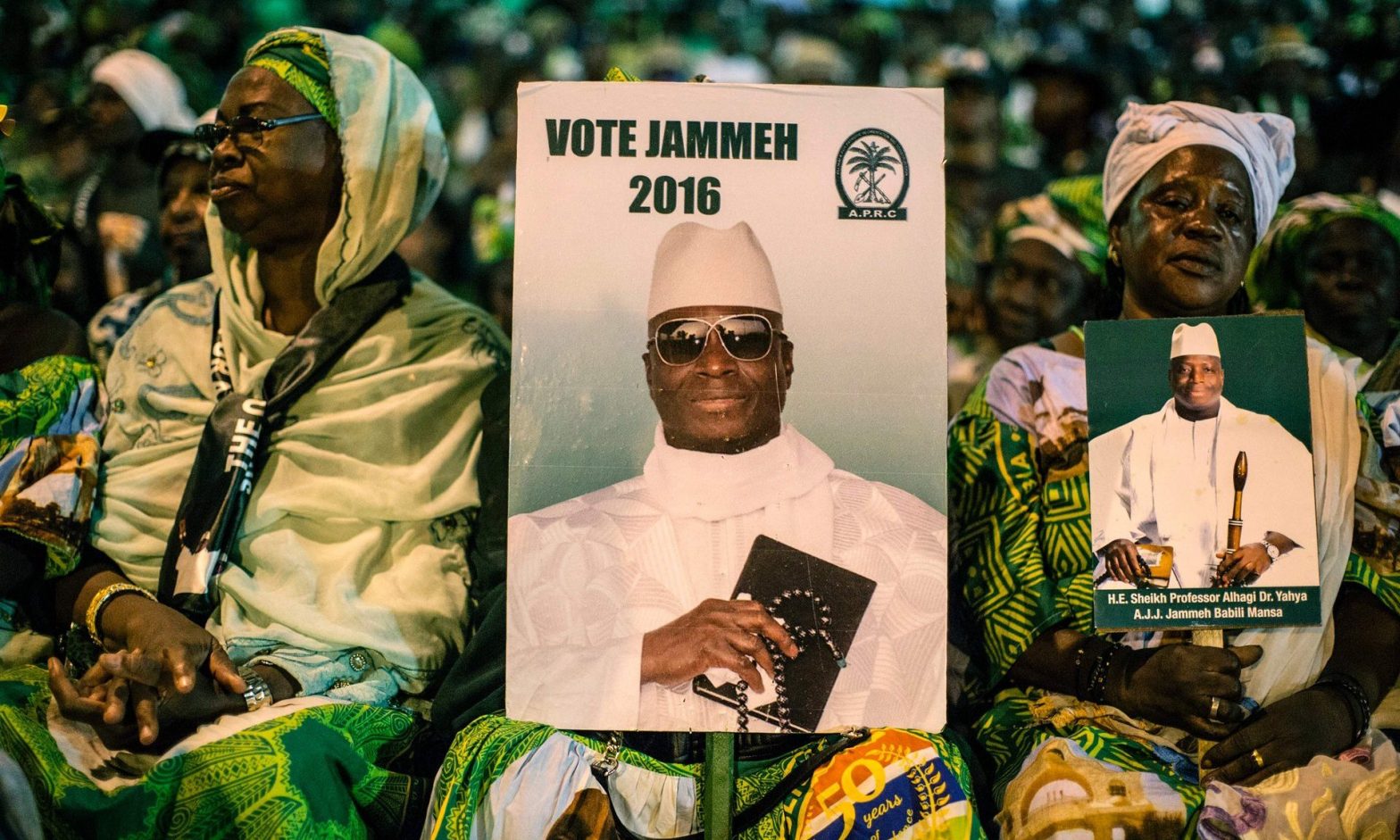

For his part, Jammeh held rallies attended by thousands of loyal supporters, many impressed with the free education and healthcare provided by the incumbent government. Shortly before the election, Jammeh told the BBC, “I’ve taken the Gambia from the stone age to a modern country.”

Jammeh did suffer from missteps during the campaign, including a speech in which he made racist remarks about the Mandinka people, who form a plurality of the Gambia’s population. But with institutional advantages–including the ability to shut down phone and internet access on election day–on his side, Jammeh was expected to prevail.

Yet when more than 500,000 Gambians went to the polling booths on December 1, casting their votes with a unique marble-based system, it was Barrow who won, 43 percent to 40 percent.

When Barrow’s victory–and Jammeh’s initial concession–were announced, thousands of genuinely shocked Gambians celebrated in the streets, some of them defacing and dancing on posters of Jammeh. Others took to Twitter in jubilation, with one opposition supporter summarizing a mood common among his compatriots by writing, “WHAT A TIME TO BE ALIVE!!!”

In an interview with the Foroyaa newspaper a few days after the vote, Barrow called for reconciliation, while the imprisoned UDP leader Darboe, celebrating his release on bail on December 5, said of Jammeh, “I would never address him as a crazy man and I never would address him as an evil man.”

Others in Barrow’s coalition, however, had more drastic measures in mind. “[Jammeh] will be prosecuted,” opposition leader Fatoumata Jallow-Tambajang told The Guardian on December 7. “This is my personal opinion–it might take three months because we really want to really work fast.” (Later, a coalition spokesman said Barrow himself had no plans to prosecute Jammeh.)

But even during the Gambia’s week of democratic hope, many in the country remained skeptical of Jammeh’s intentions. “I will only believe it when I see him leaving the state house,” one businessman warned.

Fears like these were proved correct on December 9, when Jammeh retracted his concession in a 28-minute address, recommending for good measure, “[We should have] clean, transparent elections, where nobody will be denied the right to vote, and where the elections will be supervised by God-fearing, honest, patriotic…and God-fearing [Independent Electoral Commission] members.”

For the next few days, the situation in the Gambia remained calm but tense. Soldiers patrolled Serekunda and the capital, Banjul, but there were no reports of mass unrest.

Apparently speaking from an undisclosed location where he is protected by his supporters, Barrow criticized Jammeh’s conclusion that the vote was fraudulent and needed to be re-run.

According to The Guardian, Barrow said of Jammeh, “He lost the election, called me, swore to the Qur’an and said: ‘I am a Muslim, I have faith, I lost the election. I have accepted it in good faith and our electoral system is the best in the world. No one can rig it.’ We want him to step down because he has put himself in a very funny position, in a tight corner.”

Meanwhile, at the urging of the Gambia’s neighbor Senegal, the UN Security Council held an emergency session and condemned Jammeh’s U-turn. Similar statements came from American and African Union officials.

Then, on December 13, three developments occurred that could suggest an end to the uncertainty–albeit perhaps not a happy one.

First, four regional leaders flew in to Banjul for meetings with Jammeh and Barrow. One official from the West African economic cooperation bloc ECOWAS hinted that if mediation could not convince Jammeh to step down, military intervention might be appropriate.

Second, Jammeh’s party, the Alliance for Patriotic Reorientation and Construction, filed a legal challenge against the election results in the Gambia’s Supreme Court. But this court lacks judges to hear the petition–because they were fired by Jammeh.

Third, and perhaps most significantly, the offices of the Gambia’s Independent Electoral Commission (IEC) were occupied by soldiers. No one was detained, and IEC Chair Alieu Momarr Njai later repeated his previous calls for Jammeh to accept defeat. Still, the seizure indicates that the head of the Gambia’s army, who had originally vowed to uphold the election results, has shifted his allegiance back to Jammeh.

If Jammeh somehow does relent and cede power to Barrow, it will mark a historic occasion–the very first peaceful presidential succession in the Gambia’s fifty-one years of independence.

For now, the government shows few signs of willingness to compromise, with Jammeh asserting on December 20, “Before [the regional leaders] came, they had already said Jammeh must step down. I will not step down.”

But after having tasted victory–even if only for a few days–the opposition remains equally defiant.

“There is no second coming here,” reads part of an open letter to Jammeh on the anti-government JollofNews website. “A wise man knows his limitations and does not pick a fight which he has a slim chance of winning. This is not a battle you will win, sir.”