“Why do you think you were charged under the Espionage Act?” Scott Pelley of 60 Minutes, asked Thomas Drake, a former senior executive at the NSA who, in 2010, was indicted for leaking classified information.

“To send a chilling message,” Drake replied. “Do not tell truth to power. We will hammer you.”

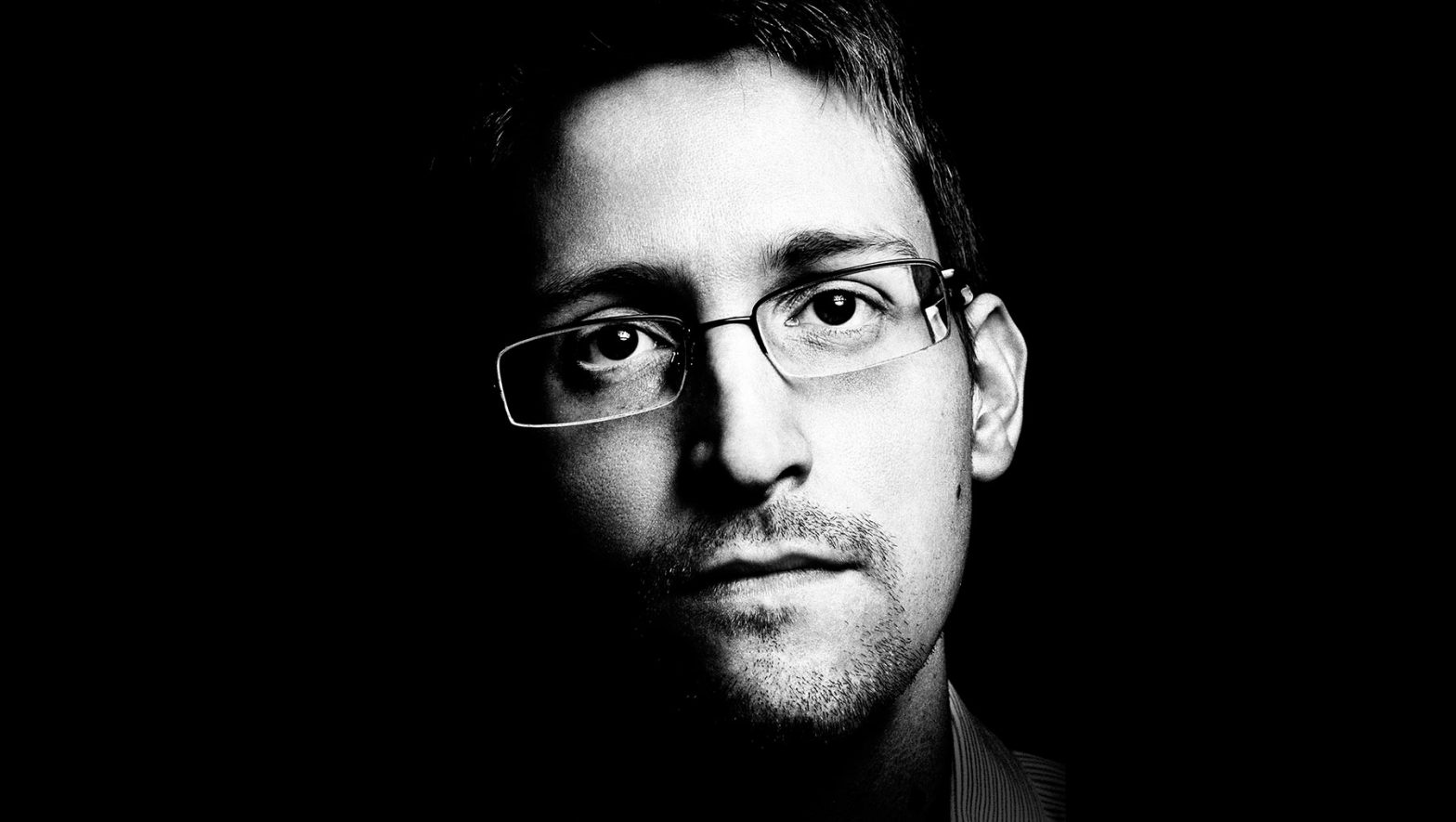

But the hammer never came down for Drake. In 2011, all ten of the original charges were eventually dropped and Drake became the recipient of the Ridenhour Prize for Truth-Telling. Edward Snowden has not enjoyed the same success.

Oliver Stone’s Snowden, which hit theaters on September 16, tells a dramatized version of its subject’s life between 2004 and 2013. Over the course of the film, he suffers damaging bone spurs, is honorably released from the Army, works his way through several locations as an employee of the CIA, and eventually develops epilepsy. Interspersed through the story, Snowden’s tumultuous love story with Lindsay Mills reveals the character at his most human.

As the movie progresses, viewers become privy to Snowden’s increasing suspicion of the NSA and the liberties the organization takes to catch the bad guys, even if it means hacking into password-protected and supposedly private platforms. When Snowden has seen too much, he takes matters into his own hands and releases thousands of private documents to the press. Is Snowden a hero or a traitor? The answer to that question depends on whom you ask.

In early June 2013, Snowden flew to Hong Kong where he released thousands of classified documents to well-established journalists Glenn Greenwald, Laura Poitras, and Ewen MacAskill. Some of the documents contained information on the metadata collection program that allowed the organization to get past presumably protected data. What Oliver Stone fails to include in the film is that the metadata collection program was not the only piece of information that Snowden passed on.

“One of the biggest misconceptions about him is that he ‘heroically’ revealed a domestic spying program in the name of civil liberties,” Rebeccah Heinrichs, a fellow at The Hudson Institute and former adviser on military matters and foreign policy to Rep. Trent Franks (R-AZ), told The Politic. “He took over one million classified files–only a tiny tiny portion had anything to do with the metadata collection program. The rest had to do with military operations and technology, counter-terror efforts.”

Others, like retired CIA operations case officer Scott Kessler, feel similarly. Snowden, he told The Politic, “took classified information on sensitive collection systems that he knew was classified and made it unclassified.” Snowden released information he promised to keep secret, and he broke that promise, compromising international security. Kessler also observes that there were plenty of alternatives to what Snowden decided to do with his discovery. “You can quit, you can make an internal complaint, you can go through the painstaking prospect of following the law,” Kessler said. “If you’re not comfortable with those then you say so and deal with the consequences [rather than running to Russia.] People who stand up for American democracy do not take shelter under Vladimir Putin.”

Others, however, point out that without Snowden’s efforts, the nation would be blind to secret data collection of private information. Loosely quoting Bob Graham of The New York Times, Llyod Gardner, author of “The War on Leakers,” told The Politic that “a government that depends on secrecy is headed for mediocrity.” Leakers provide checks and balances for the government. Perhaps without Snowden’s actions, the country would still be in the dark. Gardner further emphasizes that leakers like Snowden and Drake are not in it for the money: “They were doing it because they were alarmed at the way government money and resources were going into a program that was costly and not successful.”

As the end of Snowden’s three-year asylum in Russia approaches, the question of his fate has become a hot topic of debate. Early in September, Congress issued a report which holds firm that Snowden was not the whistleblower he claims to be. A day before the release of the report, campaigners launched a “pardon Snowden” crusade, urging President Obama to issue Snowden a pardon before leaving office in January. Such a request seems unlikely to succeed.

Snowden’s efforts may have encouraged the NSA to be more transparent and work harder to explain itself and its actions. Some even say Snowden influenced President Obama’s decision to sign the USA Freedom Act last year, an act limiting the NSA’s access to telephone data.

But even if Snowden’s leak created a public good, that does not mean he should be pardoned. Professor at Harvard Law School, Jack Goldsmith, explains in his “Lawfare” blog that “the price of the benefits were enormously high in terms of lost intelligence and lost investments in intelligence mechanisms and operations, among other things.”

There is much to learn from both sides about Snowden’s motivations for leaking the documents and about how much damage was caused by the leaks. But regardless of what is found, Snowden’s prospects look bleak. As Goldsmith notes, “presidents don’t usually grant pardons because a crime brought benefits.”