00:40 – There’s more concrete ways to deal with the legitimate concern that our border’s not secure. As it pertains to birthright citizenship, this is a right protected under the 14th Amendment. And I just don’t think it’s legitimate to say that we’re going to change our Constitution and that it’s going to solve our problem. I don’t think that’s the proper thing to do. There’s fraud and there’s abuse — you know, pregnant women are coming in to have babies simply because they can do it. Then there ought to be greater enforcement. That’s the legitimate side of this. Greater enforcement so that you don’t have these, uh, you know, anchor babies, as they’re described, coming into the country.

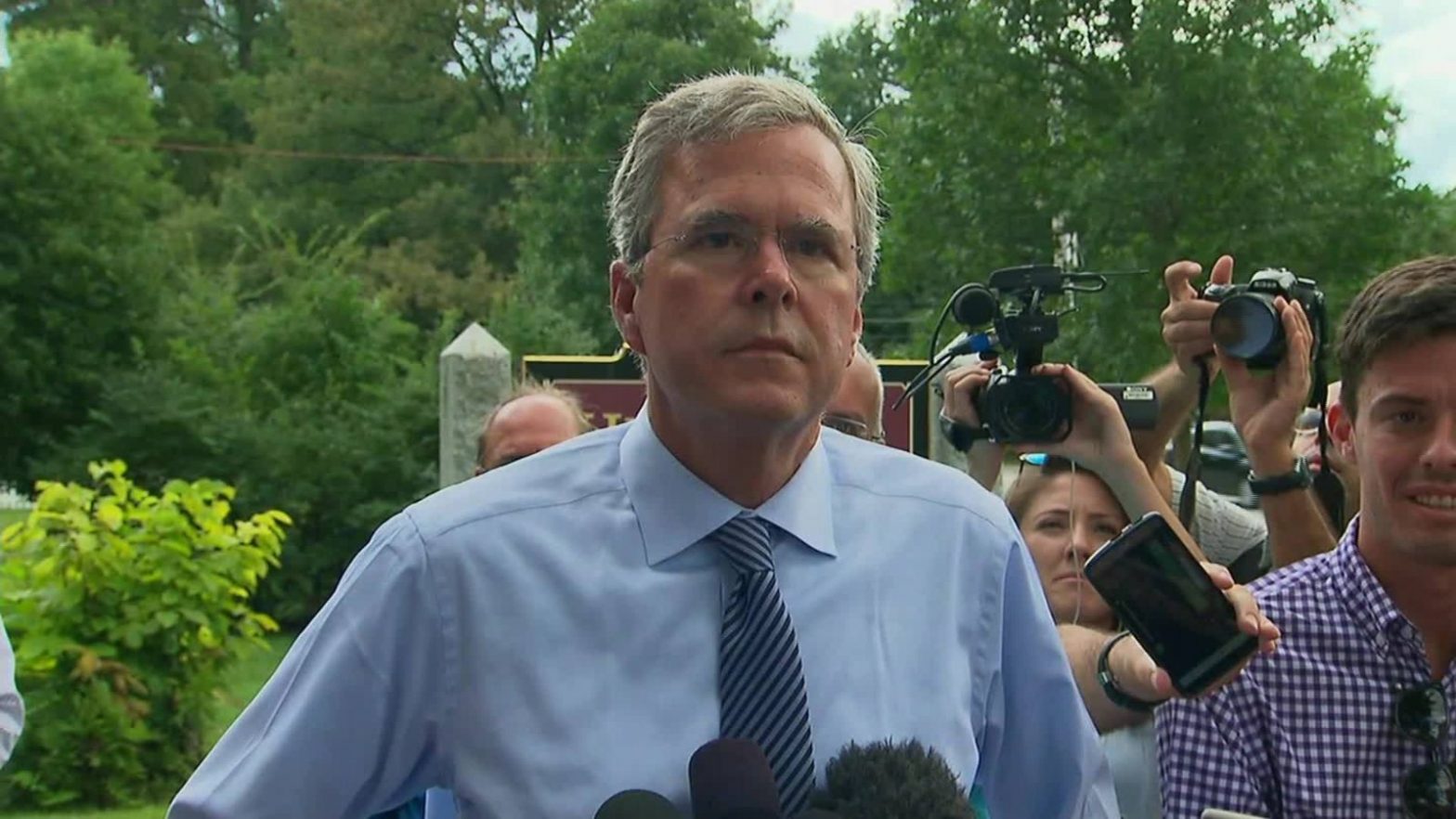

On Aug. 19, Governor Jeb Bush gave an 11-minute interview on Bill Bennett’s Morning with America. Bennett asked him about education, veterans’ affairs, and finally immigration. After weeks of Donald Trump calling for a wall at the Mexican border and the repeal of the birthright citizenship clause in the 14th Amendment, Gov. Bush was asked to comment. He made two fatal mistakes. First, he used the term “anchor baby” to describe the population of about 300,000 children, according to a Pew Research Center study, who are born to undocumented immigrants annually. Second, his argument lasted over 40 seconds.

By the time his interview hit mainstream channels, it had been reduced to seven.

With a wave of responses around the country that ranged from thousand-word thought pieces to Hillary Clinton’s curt “They’re called babies” tweet, Gov. Bush found himself in the middle of a controversy not over his policy proposals, but his word choice. Despite Mr. Trump’s repeated use of that term in a press conference earlier that week, the Florida governor was the one suddenly fighting an unwinnable battle over accusations of prejudice.

While fragments of his Morning with America statement have been shared all over the world, the YouTube videos of his full interview have drawn, at most, 300 views each.

“Ten, fifteen years ago, we had no way of virtually storing anything the media put out,” says Yale professor and political journalist Walter Shapiro. “But now everything is preserved — C-Span has wonderful archives of all of its material. Anyone can go on candidates’ websites and watch their speeches. But no one is doing it.”

The result of this is an exacerbation of a soundbite culture that, although avoidable with new technology, has been developing for over four decades.

Yale professor Joseph Roach teaches a course on classical rhetoric in modern media called Eloquence. He asserts that this simplification of issues has always been true of politics since the ancient world, but has been intensified by our current culture of mass media. Richard Nixon’s 1968 campaign — the first-ever televised campaign — introduced the concept of the newspaper quote in the new form of a sound bite. Today, digital and social media have exponentially magnified this process in the form of character and video time limits.

00:25 – To say that we’re going to change our Constitution and that it’s going to solve our problem. I don’t think that’s the proper thing to do. There’s fraud and there’s abuse — you know, pregnant women are coming in to have babies simply because they can do it. Then there ought to be greater enforcement. That’s the legitimate side of this. Greater enforcement so that you don’t have these, uh, you know, anchor babies, as they’re described, coming into the country.

In many ways, politics is like theater. It is a performance that is measured and choreographed. But more importantly, it is limited by an audience that could lose interest after every word. In crafting a political message, it is a virtue to respect the scarce attention spans of a busy public. Ultimately, politics and theater are both arts constrained by time.

The practice of concision in rhetoric is as old as politics and journalism themselves, but in today’s media we find a trend towards radical condensation — the deliberate imposition of limits on speech — that often pushes ethical boundaries and plays a large part in driving election issues.

Dr. Daniel C. Hallin is a professor of political science in the University of California – San Diego, where he studies political communication and comparative analysis of media systems. In 1988, he released a widely-referenced study which found that in 1968, the average sound bite lasted 43 seconds. Twenty years later, it was down to nine. Today, he estimates, it hovers around seven or eight seconds.

“Everyone knows that if you give long policy speeches, you won’t get on the air,” he told The Politic. “So you have to craft one-liners and photo ops.”

This fact fundamentally changes the way that politicians communicate with their audience, and how the audience acts on what they hear. This is especially true in the primary stage, where viewers are highly fragmented and volatile, according to Hallin. The 2016 election has been no exception. It is no coincidence that the brand of conversation we’ve seen surrounding immigration has come with the growing presence of politics in social media — a forum where there is no clear arbiter of discussion and where condensation is crucial. As a result, political messages have greater reach, less moderation, and an ultimately deeper impact. And those who know how to play the game, play it well.

“It’s no doubt that ‘anchor babies’ came from some [Trump] consultants who thought, ‘this is going to get traction,’” said Hallin.

00:18 – There’s fraud and there’s abuse — you know, pregnant women are coming in to have babies simply because they can do it. Then there ought to be greater enforcement. That’s the legitimate side of this. Greater enforcement so that you don’t have these, uh, you know, anchor babies, as they’re described, coming into the country.

Intentional or not, Gov. Bush’s use of the term “anchor babies” serves as a tangible illustration of the collision between two major trends in politics and media: an escalating (albeit ages-old) anxiety over immigration, and an audience that increasingly receives its information in small pieces.

Author, media specialist, and Yale professor Francesco Casetti agrees with Prof. Roach that entire arguments have become less important and instead are replaced by single sentences with sweeping impact.

“Now, we experience the world in pills,” he says. “We are in this great situation in which, for the first time, we can have a view of the entire world” — and yet, we have stopped searching for that global view.

“A pill is the world reduced,” Prof. Casetti continues. “But the pills that work best are the ones that give you a sense of the entire world. Those that hit your imagination, and allow you to build a world around you.”

The epitome of this ‘world made of pills’ is social media. Although it did not begin the trend of soundbite communication, social media distributes fragments for instantaneous consumption, with an immediate impact. The self-imposed length and size restrictions on sites like Twitter and Snapchat take advantage of words and images that could go viral.

Moreover, the dissonance between the fragments that we receive and the totality of a narrative is increasingly more traumatic. Through pieces of information, the audience constructs an idea of reality that is incomplete and often incorrect.

This effect is different from the natural process that an individual goes through when they listen to a speech and pick out the most impactful parts for on their own. Now, because acts of narration and selection are expedited, the audience loses its grip on this decision-making process. The difference can be easily seen in comparison to the Vietnam War, the world’s first televised conflict. Through time, certain images became remarkably symbolic as the public slowly went through the process of watching, reading, and digesting. “Vietnam was a great narration,” says Casetti. In contrast, “this [immigration issue] is not a great narration. It’s a pure epidermic effect. What we have are pills of anxiety.”

This particular anxiety over illegal immigration is one that has come in waves throughout history. Governor Bush is not the first to use inflammatory language towards immigrants, and Donald Trump is not the first to use it to rally nativist sentiment. Trump has correctly sensed that there is a significant part of the population that is ready to hear an anti-immigrant message.

So in seven seconds, Governor Bush suggested that the only reason why any immigrant would want to have a baby is to make an anchor. The phrase is itself a dehumanizing argument, but one that a large part of the population is eager to hear. As the clip was shared and discussed, it erupted the kind of conversations that we see now: not about policy, but about the very character of a population.

“These are people who are not particularly engaged in politics, who are often economically lower middle class, often without college degrees, wanting simple solutions to a world which is changing from the world of their birth,” says Prof. Shapiro. “So all it is is these groups simplifying these challenges facing Americans and demonizing immigrants. But the politics of immigration are really, really complicated.”

00:12 – Because they can do it. Then there ought to be greater enforcement. That’s the legitimate side of this. Greater enforcement so that you don’t have these, uh, you know, anchor babies, as they’re described, coming into the country.

The modern form of this debate has been significantly shaped by the gap between politicians and the electorate on immigration policy decisions. Although the immigrant experience has always been universal, recent conversations about policy have mostly taken place behind Washington doors.

In 2004, President Bush proposed a three-way bargain between businesses, tech communities, and politicians concerned with undocumented immigrants who wanted a path to citizenship. What would later become the guest workers program, took into account the interests of the private sector that realized its dependence on foreign workers, while appealing to the liberal elite. All groups cut a deal on Capitol Hill to give immigrants a path to citizenship in exchange for an increase in numbers of agricultural workers and high tech visas.

“It was a wonderful deal,” said Prof. Shapiro. “But most Americans were not consulted.”

This fact has played a significant role in the way this debate has been played out since the early 2000s: the sense that Washington is giving away jobs behind the public’s back has been omnipresent in the electorate’s relationship with the issue. President Bush’s program failed in 2004, and has failed every time Obama has tried to push it.

The public has always been apprehensive of dealings behind closed doors, and Trump’s campaign has reminded them that they are missing out on those conversations. He has strategically crafted the discussion to hit on fears and prejudices, and has therefore poised the public on both sides of the aisle for outrage.

It is on this stage that Gov. Bush and the media find themselves: in a population that has fragmented conversations which are repeatedly fueled by anxieties caused by their consumption of fragmented information. Prof. Casetti’s “pills” theory has played out in stark significance over the past months. And it’s undeniably ugly.

00:10 – There ought to be greater enforcement. That’s the legitimate side of this. Greater enforcement so that you don’t have these, uh, you know, anchor babies, as they’re described, coming into the country.

In a lot of ways, a developed social media network and technological community has made it possible for the public to closely scrutinize arguments. Repetition, pause, and research is a form of intellectual empowerment that the electorate has never had.

However, it has become apparent that the public is still acting and reacting in short clips instead of broader conversations. It is also speaking in sound bites. In short, we seem to have collectively lost our ability to pick moments that impact us out of a full narrative – despite the abundance of raw material for critical analysis. By doing so, we deliberately distance ourselves from policy.

When the media circulates an 8-second bite of Jeb Bush using the phrase “anchor babies,” the public becomes instantly outraged without the context of his prefacing lines. Unmistakably, the term itself is derogatory and the Governor’s press conference defense was weak. But in the middle of all this, there was a policy message that we missed.

The result is that this urgent conversation about illegal immigration has finally gripped public consciousness — but has been reduced to and shaped by arguments in sound bites. When the primary and general elections come around, individuals will be going to the voting booth with seven seconds of opinion rather than ten minutes of substantive discussion. They will remember Gov. Bush for his unfortunate use of a derogatory term and not for his argument about the absurdity of Donald Trump’s immigration policy.

In the internet age, the public should not be falling for these stage tricks anymore.

00:07 – Greater enforcement so that you don’t have these, uh, you know, anchor babies, as they’re described, coming into the country.

Thank you, sir. If you ever have 40 minutes we can sit down and talk policy.