Donald Trump wants to end birthright citizenship. He won’t. But what does the popularity of his rhetoric say about this moment in the United States? And what does it mean for immigration reform?

On May 23, 1866, Senator Howard Jacob, a Republican from Michigan, introduced the 14th Amendment to the United States Senate. He said that it gave “to the humblest, the poorest, the most despised of the race the same rights and the same protection before the law as it gives to the most powerful, the most wealthy, or the most haughty” through its guarantee of citizenship to all born on American soil.

On Sunday, August 16, Donald Trump, current Republican presidential candidate, released an immigration plan on his campaign website that includes eliminating birthright citizenship, stating “no sane country would give automatic citizenship to the children of illegal immigrants.”

Since Trump announced his proposed policy, many of his fellow Republican presidential candidates have come out with similar statements, including former Pennsylvania senator Rick Santorum, who said in a CNN interview in late August, “We have to go through the process of enforcing our laws.”

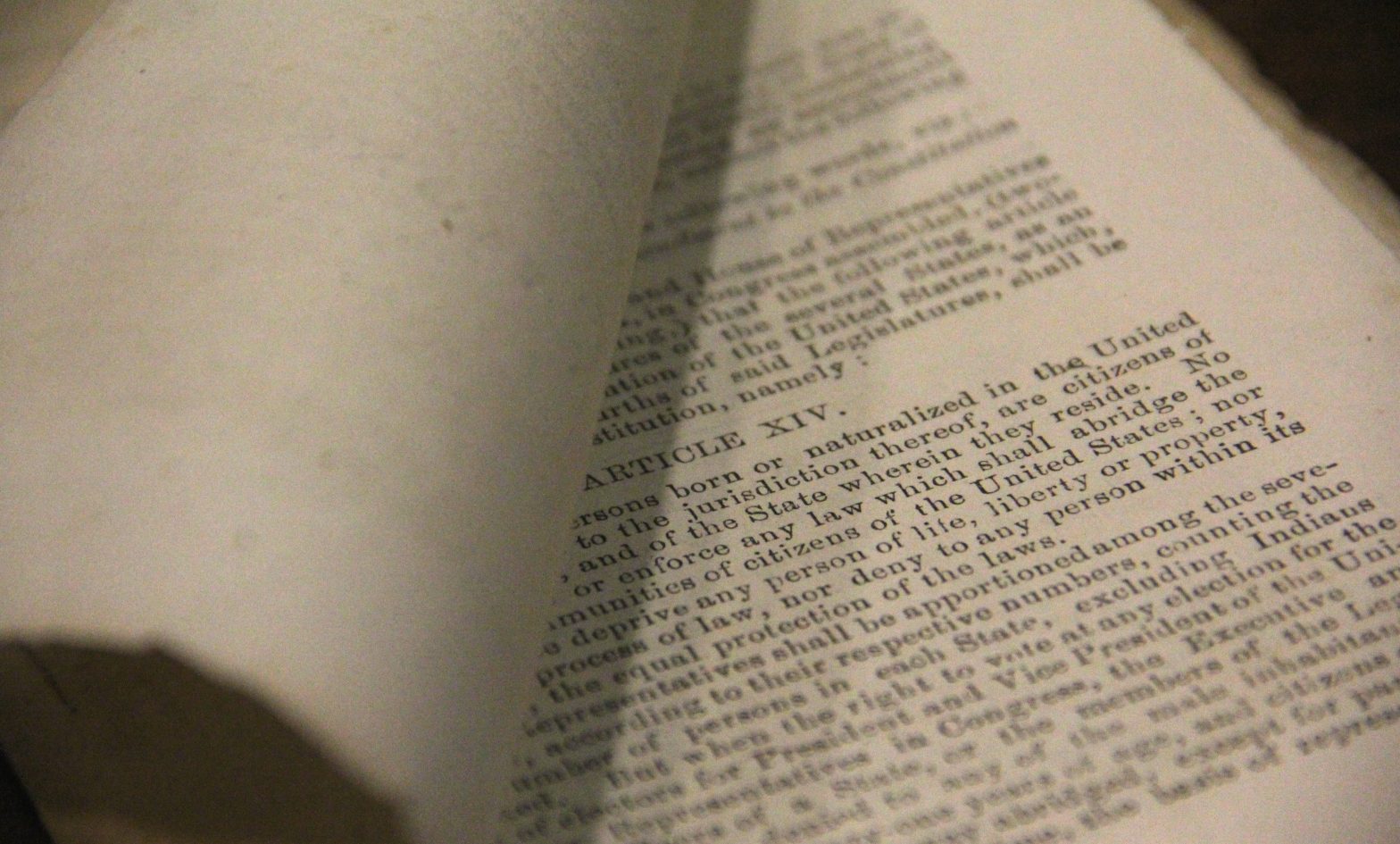

The actual law, however, disagrees. The fourteenth amendment, which states, “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside,” was originally passed by a Republican Congress. They expanded the meaning of citizenship in this way, in order to effectively overturn the previous Dred Scott decision, which had barred any African American from citizenship. In 1898, the Supreme Court interpreted this amendment as granting birthright citizenship to a child of non-U.S. citizens in the case of United States v. Wong Kim Ark.

Though Donald Trump has offered no concrete way of removing this right, he has mentioned briefly that the Supreme Court would agree with him on a reinterpretation of the amendment’s language. Looking at the clause that references jurisdiction, John Yoo, Professor of Law at UC Berkeley, offers what he sees as the sole possible argument that could even be made in favor of Trump’s view: “Congress could claim that this language requires that the parents of the children not be citizens of another country.”

This argument would have to claim that citizens of another country would have allegiance to that country and not to the United States, such that they and their children could not be “subject to the jurisdiction” of United States law. Under such a system, however, not even Donald Trump would retain his citizenship, nor would any candidate whose parents or grandparents hail from a foreign nation.

Professor Yoo pointed out that any attempt by Congress to use this argument would undoubtedly move to the Supreme Court. In fact, a similar case did reach the Supreme Court. In 2004, conservative lawyer Dr. John Eastman filed a brief in the case of Yaser Hamdi, an American who was captured in Afghanistan, allegedly fighting with the Taliban. Eastman argued that neither Hamdi nor his parents were citizens. Even though Hamdi was born in Louisiana, Eastman contended that because Hamdi’s parents were citizens of Saudi Arabia, they therefore could not be subject to the jurisdiction of the United States.

The court ignored this brief. As Lieutenant Colonel Margaret Stock, a nationally recognized immigration attorney, explained, trying to reinterpret a constitutional amendment over a hundred years later is, “if you know anything about constitutional law… a completely flaky theory.”

The other alternative path to eliminating birthright citizenship would be to repeal the amendment in its entirety, which would pose an even larger challenge for the United States. With the exception of Alaska and Hawaii, individual states don’t have additional laws guaranteeing citizenship. Without birthright, or a parent’s birthright, explains Stock, “Most of the people living in the continental United States would be basically illegal immigrants immediately on birth.”

Nevertheless, Trump and many other Republican candidates maintain that they can and should find a way to eliminate “anchor babies,” which Trump’s published immigration position describes as, “the biggest magnet for illegal immigration.” Senator Ted Cruz echoed this statement in an August 23rd appearance on CBS, when he argued that birthright citizenship “incentivizes additional illegal immigration.”

Anna Law, Constitutional Rights Professor at The City University of New York at Brooklyn, took issue with those facts. “Every immigration researcher will tell you that is dead wrong,” she said. “When you survey undocumented immigrants about ‘why are you here?’ overwhelming they say for job opportunities and a better life in the United States, not to give birth.”

Professor Yoo (who, incidentally, is a staunch Republican himself, and served in the Justice Department under the recent Bush administration) also admitted that the proposed policy change would not be effective. “It is estimated that there may be up to 12 million illegal aliens in the country. According to some estimate, the number of children born to illegal aliens in this country is somewhere between 200,000 and 400,000 a year. This is a tiny number — a consequence, not a cause, of illegal immigration.”

The fact that Donald Trump and other Republican candidates nevertheless are continuing to speak out against the citizenship clause of the fourteenth amendment did not surprise Professor Law, who described how often this issue makes an appearance in Congress, and is subsequently dismissed. “Why even propose this as a policy change if there is no policy research behind it that shows it would actually work? Because ideas don’t have to actually work to have political utility.”

The popularity of a candidate like Donald Trump illuminates not simply a general electoral shift towards the political right, but instead an anger and resentment towards both big government and foreign influences. The GOP remains split over this issue, as demonstrated by the split among candidates.

However, many voters still stand behind candidates like Trump and Cruz. Michaela Cloutier ‘18, a self-identified Republican who opposes ending birthright citizenship, offered, “A lot of conservatives are fed up with the current political climate are gravitating towards extreme candidates.” Trump has proudly reiterated that he was the one who brought immigration into the spotlight of this election season, but Cloutier ‘18 continued, “I think the idea of questioning birthright citizenship is the way the concerns of the party that have existed are manifesting themselves.”

The popularity of those extreme candidates will have consequences for both the country and the Republican Party. “It’s not just undocumented immigration that he’s railing against,” Professor Law argues, “It’s the demographic changes that immigration represents. It’s the ‘browning’ of America, it’s the cultural changes, it’s the racial changes that immigration represents, that a sector of the American population is uncomfortable with.” This fear and prejudice is a social phenomenon that Yoo attributes to tough economic times, during which he says, “Immigration always becomes a controversial issue.” But the topic has struck a nerve deeper than fiscal uncertainty.

In August, The Atlantic ran an article asking Trump supporters to “set forth their thinking” in their own words. “Those of us who buy into Trump’s vision, nearly to the point of blind trust, are loudly professing our disgust with the current immoral situations that taint and threaten our blueprint of the American dream,” one supporter explained. Another echoed this sentiment, saying, “We are desperate. Desperate people do desperate things.”

Trump’s polling success and strong support base seem to agree, demonstrating a critical mass of people who are “desperate” enough to eagerly go along with his framing of American immigration. “As an immigration researcher, it pains me because he has normalized the discourse and the vitriol he is spewing against immigrants,” said Professor Law, focusing on Donald Trump. “The kind of hate and racism and nativism he’s spewing, this is par for the course now.” The current rhetoric of “building a wall, and anchor babies, and repealing the 14th amendment,” she explained, is shifting the focus away from effective plans for immigration reform.

The implications of this changing public discourse are pervasive, and many Republicans are concerned by the direction Trump is driving their party on this issue. Stock articulates this view: It does pose significant problems for the Republican Party because if you look at the demographics, folks with a parent who wasn’t born in the United States are a significant chunk of the voters and they’re not likely to feel favorably on that particular issue when a candidate says they shouldn’t be citizens.” The conversation will potentially isolate the more than 1-in-5 Americans who are first or second generation citizens, according to the most recent census.

Trump’s instigation of the birthright citizenship debate will have the opposite of his desired effect. Cloutier ‘18 suggested that the candidates who are supporting eliminating birthright citizenship will only access a particular demographic of the Republican Party: “The uneducated part of the vote.” Stock echoed this statement, arguing, “If they care about the issue, and they’re knowledgeable about it, they’re either going to be Independents or Democrats when they hear Republicans saying crazy things.” If this takes on national significance as an issue in the general election, the Republicans could meet their demise as a result.

Looking past party lines and the election, Professor Law saw in the dialogue Trump has created a greater consequence. According to her, he has “done lasting damage to the cause of actually fixing immigration reform, which both parties agree is profoundly broken.”