Past Ingalls Rink up Winchester Avenue, where plywood boards fill windows and broken bottles sit in potholes, sprawls Newhallville, a predominantly black neighborhood with more ivy on its walls than Yale. On the corner of Winchester, Munson, and Henry is a former gun factory, the Winchester Repeating Arms Company. There are many sides to Winchester, and everyone tells a different story about its rise and fall.

Once home to a multi-million dollar arms manufacturer, the factory complex today is split into two courtyards. The street-facing courtyard has recently been renovated. Clean brick walls and dark-paned windows ensconce a brand-new apartment complex. The rear courtyard, untouched since the factory closed in 2006, is hidden from street view — its abandoned spaces covered by crabgrass, grime, and graffiti. To get inside the ruins of the old courtyard you must squeeze through a two-foot gap in a chain-link fence. Swallows nest in the rusted pipes and mosquitos breed in pools of stagnant water. It’s desolate, but full of life.

Back in the renovated courtyard, saplings border a concrete quad near a large electrical generator. One afternoon this summer, two-dozen people gathered here for the grand opening of the 160 apartments of Winchester Lofts. Men sporting ties and tailored suits and women clad in black dresses came to watch the ribbon cutting ceremony, impervious to the punishing 90 degree heat of the cloudless day.

Bruce Alexander ’65, Yale’s Vice President for New Haven and State Affairs, comes to the podium. “New Haven is a city on the move,” he says. Alexander has reason to celebrate. Since 1983, the city and Yale have been partners in a renovation project to revitalize the beleaguered Newhallville neighborhood. These new apartments, built by Forest City Real Estate, sit in the middle of Science Park, an 80-acre plot of industrial wasteland that the Science Park Development Corporation has been transforming into a technology enclave. Forest City builds a wide range of office spaces and apartments in large cities across the country.

A younger man steps up to speak. He stretches out his arm, fingers spread toward the far wall of the courtyard. “They don’t make buildings like this anymore,” the man says. This is Tim Sullivan, a former Barclays investment banker turned Deputy Commissioner for the Connecticut Department of Economic and Community Development. Sullivan thanks Yale, the architects, the developer, the city, and the state for the new apartments. Sullivan closes with a promise: “To honor the past and keep it with us as we move forward.”

Winchester Lofts, 700,000 square feet of apartment in a factory setting, claims to be the “intersection of past and present.” Built with “genuine craft,” to quote its brochure, for young professionals looking for “the feeling of authenticity,” Winchester Lofts offers an “artisanal” living experience. “The aged factory,” reads a plaque in the lobby, is “rich with history, texture, architectural craft, and stories untold.”

But to say that the new lofts preserve or embody the building’s industrial past is a revisionist history. The spirit of the old factory and the new lofts are as different as leather and lace, and the machinists who made guns here have been replaced by plush rugs and matching faux-leather furniture. The new apartments embody a deeply stratified class system in America, and in New Haven, that is evident by walking a few blocks in any direction. The lofts are pricing out Newhallville residents. Yet most developers and historians cringe at the use of “gentrification” to describe how this neighborhood is changing. This presents a challenge in definition. What exactly happened at Winchester? Will the new lofts change the neighborhood for the better, or for the worse? Gentrification may be the future of the American city. But its cost may be the erasure of history.

The project to turn an old gun factory into upscale apartments started in 2008, but the story of Winchester began in 1855.

By the middle of the nineteenth century New Haven already produced many of the nation’s carriages and clocks— and soon it would become the gun capital of the world.

In 1855, inventors Horace Smith and Daniel B. Wesson moved their fledgling firearms factory to New Haven. The Volcanic Repeating Arms Company set up shop on the corner of Orange and Grove Street and employed fewer than 50 people during its first year, Despite considerable investment by 33 of New Haven’s wealthiest businessmen, the Volcanic rifle was a failure, and within two years, the company began flailing financially. Oliver Fischer Winchester, a beefy man who wore large black coats and cowboy hats, bought the company’s assets and changed its name to the New Haven Repeating Arms Company.

Winchester, a successful clothing manufacturer, saw promise in a young firearm designer named Benjamin Tyler Henry. Winchester hired Henry as the factory’s superintendent, and within three years the company had built a larger factory across the train tracks on Artizan Street and had a patent on a new .44 caliber rifle.

Nicknamed the “Henry,” the new gun was a huge success. With the start of the Civil War in 1861, the gun market exploded. Although the Henry rifle was designed for sport, not combat, Union soldiers preferred this gun to those made by the Spencer Company— the lever-action design allowed for faster shooting, and the Henry had greater firepower.

The Henry helped the North win the Civil War, and after the war it would help the United States win the Western frontier. The Henry was redesigned in 1866 as the “Winchester 66” and became the gun of choice for buffalo hunters, pioneers, and sheriffs across the expanding frontier. Both Apache leader Geronimo and President Theodore Roosevelt carried models of the Winchester 66. Even John Wayne used a Winchester.

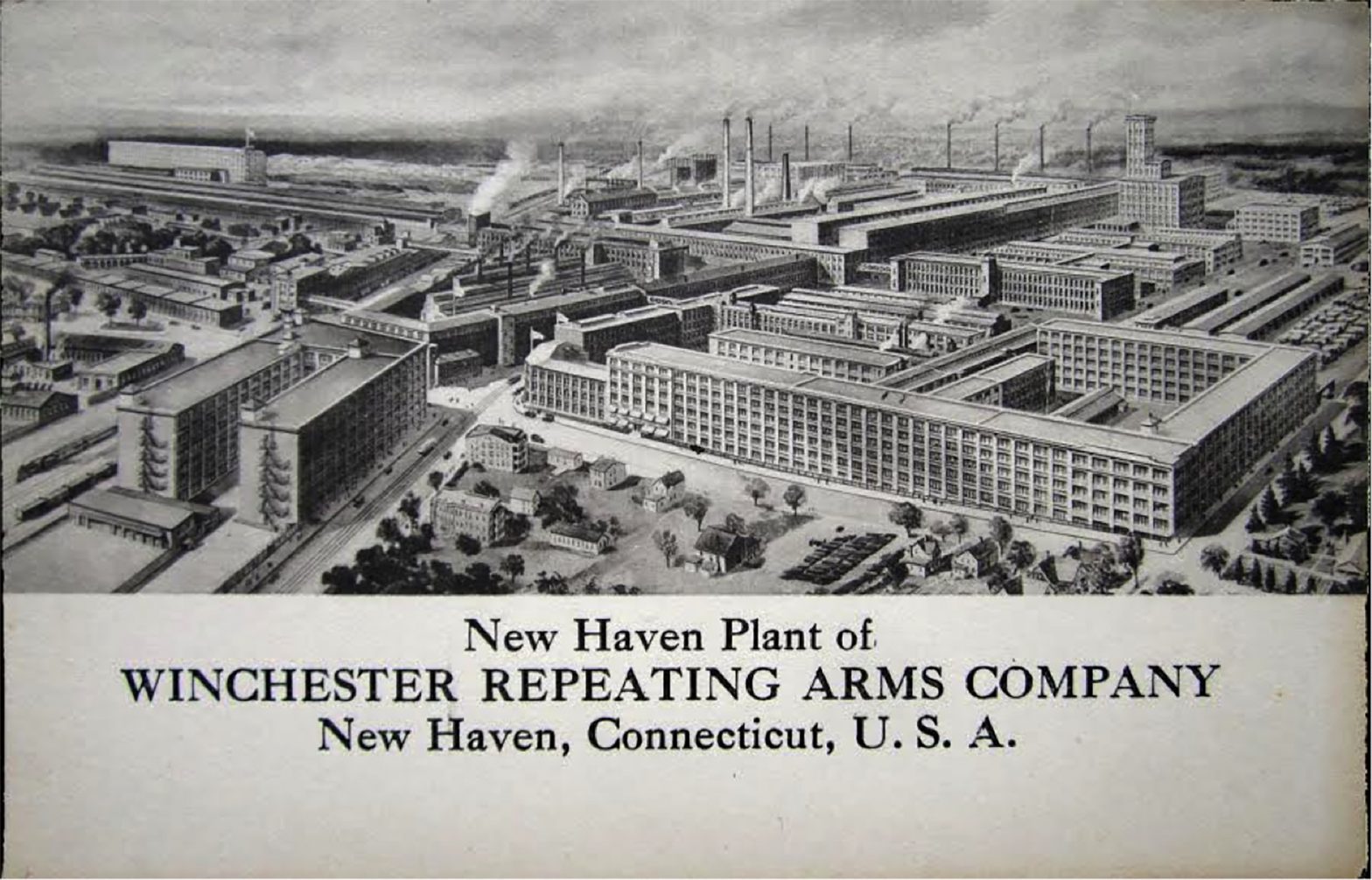

Through the rest of the nineteenth century, Winchester expanded. In 1869, it bought out the Spencer Company, Winchester’s only large competitor. When Winchester received a bid from rifle contractors during World War I, Winchester managed the near-impossible task of building a factory overnight. Most of the factory near Newhallville was built in less than a year, covering 82 acres and employing 16,000 people.

After the war, Winchester continued to grow, becoming the domestic primary supplier for a growing American gun culture. By 1917 the company had produced over six million guns and rifles. An annual report to the company’s stockholders from that year states that shooting licenses in the U.S. had increased to five million. Winchester documented that over 1,000 new gun clubs were founded, and high schools in dozens of states held courses in marksmanship.

“An important development in the arms and ammunition business has taken place,” reads the stockholder report. “Thousands of new shooters are taking up this popular sport. Thousands of those who formerly used guns are again turning to their favorite pastime.” The market for guns shifted from military to sport, and Winchester responded.

Guns were not just recreational. Shooting became a tool for teaching maturity and morality. Fathers were encouraged to take their boys hunting. After all, Winchester marketed its .22 caliber rifle as “your chance to make a pal of your son.”

The American public had fallen in love with the gun. The covers of the Winchester Record, a monthly magazine circulated among company workers, evolved during the post-war years. After 1918, the magazine cover traded images of American soldiers for pictures of families hunting together. Industry and manufacturing promised a bright future for the working classes who ran the factories and ensured a recreational lifestyle for the leisure class. The Winchester factory had become its own city within New Haven. It employed 50 security guards, an emergency hospital staff of 17, and even had its own marching band.

Cities change, and the Winchester Factory set New Haven’s course time and again. Across America the cost of skilled labor rose through the 1950s and 1960s, forcing companies to cut costs any way they could. Winchester guns were well-made, but many of the parts were also handmade. To stay afloat, in 1964, Winchester replaced its older guns with a new line of cheaper models.. The quality of the weapons decreased, and with it, Winchester’s sales.

In 2006, after a century of falling in and out of bankruptcy, Winchester laid off the 186 remaining employees, and shortly thereafter announced that it would not reopen the New Haven factory. The license to make Winchester rifles was sold to Browning Firearms, which operates out of Utah. You can still buy a new Winchester rifle (most cost around $1,300), but it will no longer come from New Haven.

Because Winchester was far from self-sufficient, its departure weakened other industries. A network of New Haven factories supplied each other with materials.

“The wood came from one place, the gunpowder was made somewhere else,” New Haven historian Rob Greenberg said. “As different businesses went out, it was a telltale sign that the industrial age was coming to an end.”

When Gauthier worked at Winchester, from 1973 to 1996, the factory was only one of many local industries. Down Winchester Avenue was the G&O Radiator plant, and a brass mill employed around 600 people two blocks away.

“Along Winchester Avenue at that time you had all kinds of auto parts stores, small mom and pop stores, restaurants, and soul food,” Gauthier said of Newhallville in the 1970s. “You had a pretty thriving community.”

But relations between the community and the factory deteriorated in 1979 when the Winchester machinists union went on strike to prevent cuts to wages and benefits.

“With the 1979 strike you see the decline of Winchester and the city’s manufacturing days,” he said. “It was a turning point in terms of labor’s influence and labor’s ability to make a difference.”

The size of the strike, and its impact on Winchester’s production costs, made Winchester rethink its presence in New Haven. The company began to downsize the New Haven factory, and the number of employees at Winchester fell from 2,300 to 800 in the few years following the strike. And when the nearby brass mill closed, the G&O factory followed suit, putting hundreds more out of work.

“You could literally see the mom and pop stores closing, the restaurants closing,” Gauthier said. Winchester could no longer afford to stay in New Haven, and the community that relied on its jobs was coming apart at the seams.

“A lot of those people who lived in the Newhallville area worked at Winchester or with G&O,” he said, adding that when they were laid off, many took to the streets. “People turned to alcohol and drugs to deal with the situation. The community really suffered a real downturn.”

Crack cocaine became popular in Newhallville, and soon unemployment and crime were rising throughout the city. Yale School of Management Professor Douglas Rae is author of the book City: Urbanism and Its End, a portrait of New Haven and of urban decline. For Rae, the era of New Haven as a post-industrial wasteland is ending.

“This is the fifth scene of the third act,” he said. “De-gentrification has been the big story for a very long time.”

For seven years the factory sat vacant. Then came the new lofts. Forest City spent $10.6 million on the lofts, also taking out a $23 million bank loan to fund the first phase’s $59.26 million price tag. They broke ground in September 2013, replacing 40,000 square feet of wood decking and remaking the guts of the old factory. Toxic materials like asbestos and lead were removed. It wasn’t cheap to build, and it’s not cheap to live in, either. A studio apartment here costs $1,300 a month, but renters can pay up to $3,000 a month for a two-bedroom. The lofts boast amenities like a gymnasium, yoga and kickboxing rooms, and a dog-washing station.

But Rae said the lofts are not a sign of gentrification, at all. “I wouldn’t even pull the word out of the dictionary,” he said. Winchester Lofts might be more expensive than other homes in the area, but Rae said New Haven still has plenty of low-end real estate to spare. This sounds like a win-win for the neighborhood, but Rae said the new lofts are not guaranteed to succeed.

“[The project], as capital investments in real estate go, is pretty risky,” Rae said. The city’s residential market is saturated. “If you were doing real estate finance 101 this would be somewhere at the back of the book as an unusual strategy,” he added.

Yale has been the largest developer of Science Park, moving 800 of its employees here and building a parking garage. Higher One, a financial services company, also moved into a section of the Winchester factory in March 2012. The company was founded by three Yale graduates, and has been called “New Haven’s Google” by local newspapers.

Because the building is of historical significance (the district is listed on the National Register of Historic Places) the lofts were partially paid for with national and state tax credits amounting to $19.6 million. But these tax credits put limitations on what Forest City could build. For example, brick walls had to stay exposed and wooden support beams had to be kept in the roof. The windows were designed to replicate the original factory windows. Before construction could begin, the blueprints had to be approved by a state historic preservation officer and a National Parks Service reviewer.

The lofts claim to be more than just a new apartment building. They “reveal beauty amidst [the factory’s] hidden chambers.” A Boston-based photographer captured images of the decrepit factory that hang in the hallways. A local artist made woodcarvings of old wood beams that now stand in the lobby. An old factory door is now a conference table, and Winchester Rifle ads are memorialized as posters throughout the lofts.

Abe Naparstek is the senior vice-president of Forest City. The nearby Newhallville community is glad to see lights back on in a long-vacant building, but many residents are concerned the city may be passing them by. Although Forest City ensured 25 percent of the construction workers were minorities and that 25 percent were New Haven residents, most of the apartments’ residents will have higher incomes. 80 percent of the lofts cost market rates; the remaining 20 percent are for middle and low-income people.

Winchester Lofts will soon expand to the upper courtyard of the old factory. The next phase is about halfway complete and will bring 200 additional apartments to the 160 already in the south courtyard. The 40,000 additional square feet would include a small park exclusively for residents, an outdoor WiFi lounge, a bocce court, a swimming pool, and an outdoor grilling kitchen. Naparstek expects a nearby retail space to fill with shops once more people move into the lofts.

Professor Rae also expects the area to flourish as a result of the new lofts.

“It’s quite possible that there will be a modest resurgence of small retail,” he said. “Middle class citizens coming in and out every day is likely to be a good thing.”

Forest City claims to engage the community, but Newhallville residents are less enthusiastic about the new apartments. Gauthier said he is wary of the power of large organizations like Yale in his community.

“We don’t have a force ready to deal with the huge power that Yale University has on influencing the political scene in New Haven,” he said. “It’s very important that we maintain an active political force like Newhallville Rising and New Haven Rising.”

These two groups advocate for increasing the number of jobs in the city that go to city residents instead of people who live outside New Haven and commute. But some see organizing labor as an uphill battle. Although Yale recently promised to create 500 new jobs, the new positions may not be union-affiliated. Yale’s relations with its two unions—Local 34 and Local 35—are tense, and it does not recognize or negotiate with GESO, the Graduate Employees and Students Organization. GESO has protested repeatedly on campus for better pay and greater departmental diversity. The union’s protests fall on Yale’s deaf ears.

“[Yale-New Haven] hospital and Yale spend millions of dollars to change how people look at organized labor,” Gauthier said, adding that Yale, Albertus Magnus College, and the city are “marching right through the community and establishing a base to change how that community looks.”

Gauthier said he believes in the ability of a good-paying job to turn someone away from drug dealing. By bringing jobs back to Newhallville, Gauthier expects many of the area’s problems to dissipate. And he is not alone in this belief— in June over 1,000 New Haven workers called for more jobs opportunities in the city, targeting New Haven’s biggest employers: the University and Yale-New Haven Hospital.

Today, much of the city’s violent crime still happens in Newhallville. Just this spring, two men robbed a Yale Undergraduate at gunpoint there. Two years ago, an 83-year-old Yale architecture professor was attacked at 32 Lilac Street, the site of a Yale-designed house. Because of the incident, Yale removed the newly installed foundation and ceased construction. Even the U.S. government acknowledges that crime is a problem here. Last year the city got a $1 million Byrne Criminal Justice Innovation grant from the U.S. Department of Justice to strengthen the Newhallville community’s relationship with police.

The neighborhoods around Winchester are changing, and not just because of the Lofts. Naparstek called the once vibrant nearby Cardinal Club a “notorious and dangerous bar where there were a lot of violent incidents.” The city recently green-lighted the space to become a Café G bakery-cafe.

“I would rather have people buying croissants and expensive coffee than getting shot,” Naparstek said. “Is that gentrification? I don’t know.”

Cities like New Haven are making a comeback across the country, said Naparstek.

“Urban areas of America are getting tremendous interest from young professionals and millennials,” he said. Fewer young people are buying houses and are instead renting homes in cities where they can walk everywhere, Naparstek said.

What are the effects of gentrification? It depends on who you talk to. Rob Greenberg, who grew up in New Haven, said he dislikes the word gentrification for its negative connotation.

“People look at gentrification like it’s a rich man’s game,” he said. Instead of destroying communities, gentrification can improve struggling areas and raise the quality of life for the poor and underprivileged. The same neighborhoods that held vibrant factory communities are now places full of violent crime and drug use, said Greenberg. The Winchester Lofts development is good for Newhallville because it increases the property value of all the houses in the area, he added.

But Greenberg said gentrification and rising real estate do present a significant problem: they price people out. Greenberg compared what is happening in New Haven to areas of New York City like Brooklyn, where he currently lives. Not only does the cost of living rise, but big business also begins to wield undue influence on the community, he said.

“I’ve watched the process,” he said. “Large money will start to dictate the formula of the new town…all these tiny signature places that were part of the DNA of New Haven are starting to be washed away by developers and Yale, who are trying to dictate the shape of the new town,” Greenberg said.

Educated Burgher and Culter’s Records and Tapes—two single-location stores once on Broadway—have closed permanently to be replaced by chain stores. This gradual elimination of the city’s unique identity troubles Greenberg, who works to preserve New Haven’s history whenever he can.

“If you use the history of New Haven, if you celebrate that history you can educate future generations,” he said, and it is for history’s sake that Greenberg praised the new lofts. Sometimes the only way forward is to look back; this is the philosophy of the new lofts.

“[Forest City] brought back the essence of the building, they celebrated the architecture…Winchester is on the right path,” he said.

But Gauthier is of a different mind. He pointed to the Board of Alders’ failure to address gentrification in New Haven. “Nobody is making it an issue right now,” he said. “They don’t take action in a unified way.”

“Most people who live in Newhallville cannot afford the kind of rents that are being pushed forward,” Gauthier said. Long-term homeownership strengthens a community, he added. People care for their houses, respect property, and get to know their neighbors. Many of the Newhallville residents have lived there for upwards of 30 or 40 years. The new tenants of Winchester Lofts, Gauthier fears, will move out after only four or five years.

The high cost of living was also a problem at Winchester a hundred years ago. An opinion piece in the Winchester Record praises the power of hard work and exalts industry as a path to a better society. Manual labor was at the center of the Winchester worldview, and any reluctance for this kind of work was immoral, almost unpatriotic.

“What if a man is not willing to produce as much as the other fellow?” asked the Record. “That means he is parasitic…We cannot have unless we earn.”

Faith in industry, an egalitarian work ethic, a respect for blue collar work—these are elements of New Haven’s past that should not be forgotten, even as the city rides the technology boom into the future.

“The conditions in which people toiled [at Winchester] for generations was hard and loud, and sweaty,” Greenberg said. Today, the only sweating done at Winchester is on the treadmills in the first floor fitness room.